As the clock hits nine on a fresh winter morning, fish swim lazily in a small aquarium in the reception of the Hotel Goris as a group of men stroll past, heading outside for their first cigarette of the day. There isn’t much to do other than smoke and drink for those stranded here, victims of the blockade of the Lachin Corridor by Azerbaijani ‘eco-activists’. Azerbaijan maintains the protests blocking the road are not a blockade.

The corridor is Nagorno-Karabakh’s sole connection to Armenia, and the only way in for imports of food and other goods.

While around 120,000 people are trapped in Nagorno-Karabakh, facing empty supermarket shelves and intermittent power cuts, more than 1,000 are stuck on the Armenian side of the corridor, away from their homes, families, and livelihoods.

[Read on OC Media: Nagorno-Karabakh under siege]

For many of these people, their temporary home is Goris, a town of 20,000 in southeastern Armenia.

One of the residents of the Hotel Goris is Margo Baghdasaryan. She travelled from Stepanakert to see her cardiologist in Goris on 12 December, passing through the location of the blockade just half an hour before protesters blocked the road. She misses her husband, who has been hospitalised in her absence.

As the sounds of people playing table tennis echo around the hotel, Margo highlights her attachment to her homeland.

‘During the 2020 war, I didn’t go to Armenia. I stayed in Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh]. If something happens again, and I am given a weapon, I will hold it and try to protect my land.’

Lines of contact

The road from Goris to the beginning of the corridor runs east through a strip of land, roughly 20 kilometres long and wide, surrounded on three sides by Azerbaijani forces. Tensions can be clearly seen and felt in the villages here.

Elza Khacyan lives with her husband Grena and other relatives in Kornidzor, a village near the border inhabited by around 1,100 people.

‘We go to sleep and we wake up in fear,’ explains Khacyan.

Kornidzor’s exposed location is one reason why many residents are members of Ashkharazor, an Armenian territorial defence organisation. One of them is Ruben Balyan, who stores a Kalashnikov at home and keeps watch at night. From his balcony, he can look across a small valley at an Armenian position, and then at an Azerbaijani position, on the brown hilltops a few hundred metres away.

Sharing Goris with those stranded there are a number of the 2,000-strong Russian peacekeeping force charged with securing Nagorno-Karabakh and the Lachin Corridor.

Russia’s influence in Armenia has remained strong since the fall of the Soviet Union. Aside from the peacekeepers, a large base in the northern city of Gyumri is home to approximately 3,000 troops, and public support for Ukraine is lower than in neighbouring Georgia.

The commander of a frontline Armenian position, just 400 metres from the nearest Azeri soldiers, believes that ‘Ukraine should be grateful for anything it gets’ from the war.

But while peacekeepers are a common sight around town in shops and restaurants, attitudes towards them aren’t entirely positive. Many people say that the Russians could end the blockade with one phone call, but choose not to so that the government in Yerevan ‘realises who is in charge’.

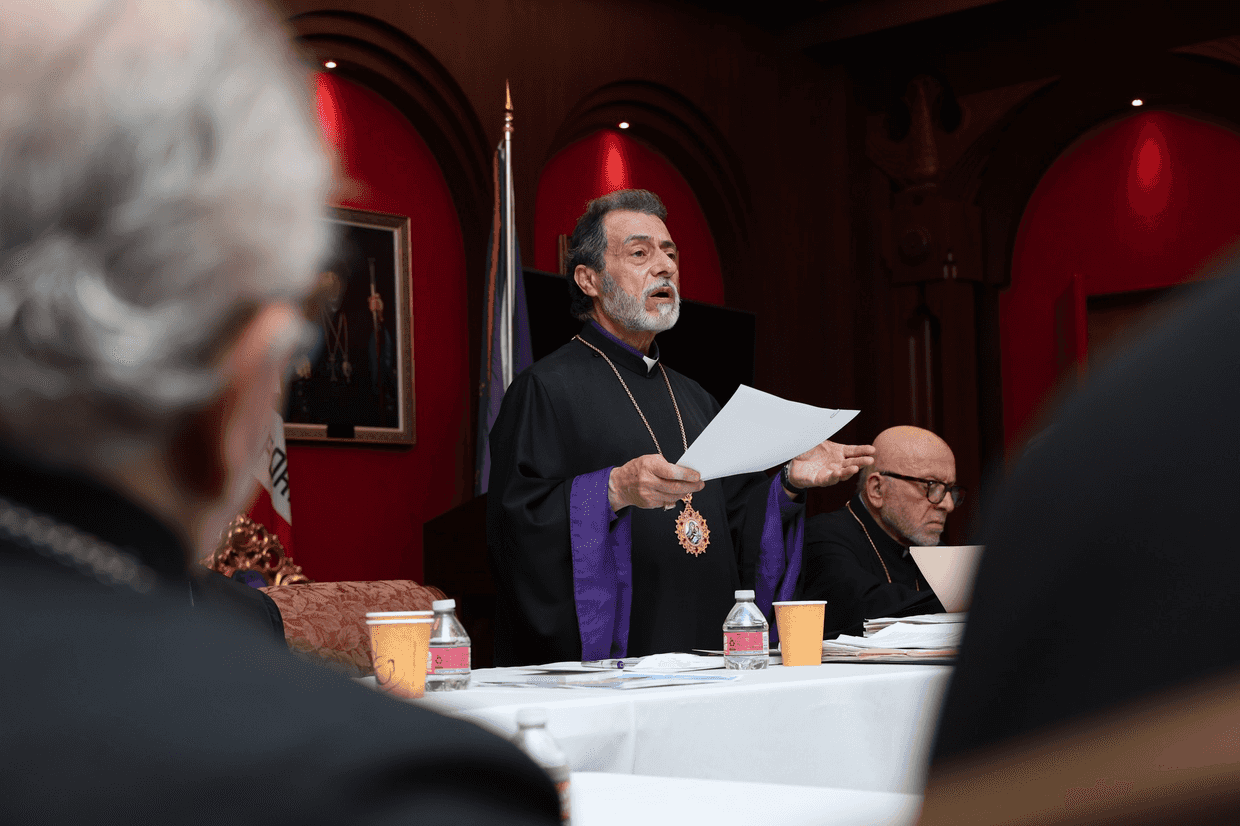

Two weeks after the blockade began, a senior Russian officer attended negotiations with ethnic Armenian protestors from Nagorno-Karabakh. The protestors demanded action from the Russians, and received a promise that the issue would be ‘resolved’ on 26 December. The situation remains unchanged.

But Nerik Mirzakhanyan, a father of two who was travelling from Russia to Stepanakert with his family to obtain a passport for his youngest daughter, believes that blame also lies with the government in Yerevan.

‘The Russians could open the corridor now if they wanted to, using force if necessary, but the Armenian government is guilty. Pashinyan isn’t experienced enough to deal with the Russians, and as a result, the Russians aren’t acting’, says Mirzakhanyan.

Like others, Mirzakhanyan also believes that the closure of the Lachin Corridor is a pressure tactic by Azerbaijan’s government, aimed at realising the ‘Zangezur Corridor’: a route that would link Azerbaijan with its exclave of Nakhchivan through Armenian territory.

Songs, dances, and solidarity

New Year’s Eve in the Hotel Goris is an odd affair. A large dinner is attended by most of the people staying there. Men sing a cappella folk songs while the children meet Santa Claus and dance. People try their best to enjoy themselves, although the large amount of vodka and wine consumed leads to a tense encounter outside that doesn’t quite escalate into a fight.