Historian Ibragim Kostoev has reported that eight years ago, the Ingush Parliament secretly withdrew from consideration a draft law that would have banned the ‘glorification of the memory of Joseph Stalin’ in Ingushetia.

In a recent inquiry, Kostoev noted that he was unable to find the text of the law on the parliament’s official website. When he questioned this, he received a message stating that ‘in accordance with the requirements of the republic’s Prosecutor General’s Office, this draft was withdrawn from further consideration’. Until then, no public announcement about the withdrawal had been made.

The draft law, which received wide attention, was first adopted by the Ingush Parliament in its first reading in February 2017. It envisaged a ban on the installation of monuments or other forms of glorifying Stalin on the territory of Ingushetia, a ban on naming streets, settlements, or organisations after him, as well as a ban on publicly justifying or praising Stalin and displaying his images in public and administrative premises.

The initiative coincided with the 73rd anniversary of the mass deportation of Ingush and Chechens carried out on 23 February 1944 on Stalin’s orders, known under the codename Operation Lentil. At that time, around half a million people were forcibly deported from the Chechen–Ingush ASSR, tens of thousands of whom died en route or in places of exile.

Despite passing in its first reading, the law faced criticism. Representatives of Russia’s Communist Party (KPRF), in particular MPs Valery Rashkin and Vladimir Kashin, spoke out against the initiative. Rashkin complained to the Prosecutor General’s Office, stating that the law ‘violates the principle of equality before the law and infringes citizens’ right to freedom of speech and expression of opinion’. Kashin, speaking on behalf of the party, claimed that ‘the deportation of Ingush and Chechens on Stalin’s orders in 1944 benefited the peoples of the North Caucasus’.

‘The Vainakhs [a term for Chechen and Ingush people] have no grounds to be offended by Stalin: when making the decision on deportation, the authorities wanted to protect the highlanders from reprisals by the fascists’, Kashin said.

In turn, the speaker of the Ingush Parliament at the time, Zelimkhan Yevloev, promised that the law would be adopted ‘in any case’.

‘Some people may hold another opinion about Stalin’s crimes, let them think so, but we will go to the end, we will consider and adopt the law in any case’, Yevloev told Russian media-outlet Kommersant.

However, later, work on the draft law was frozen, though its subsequent withdrawal was never publicly announced.

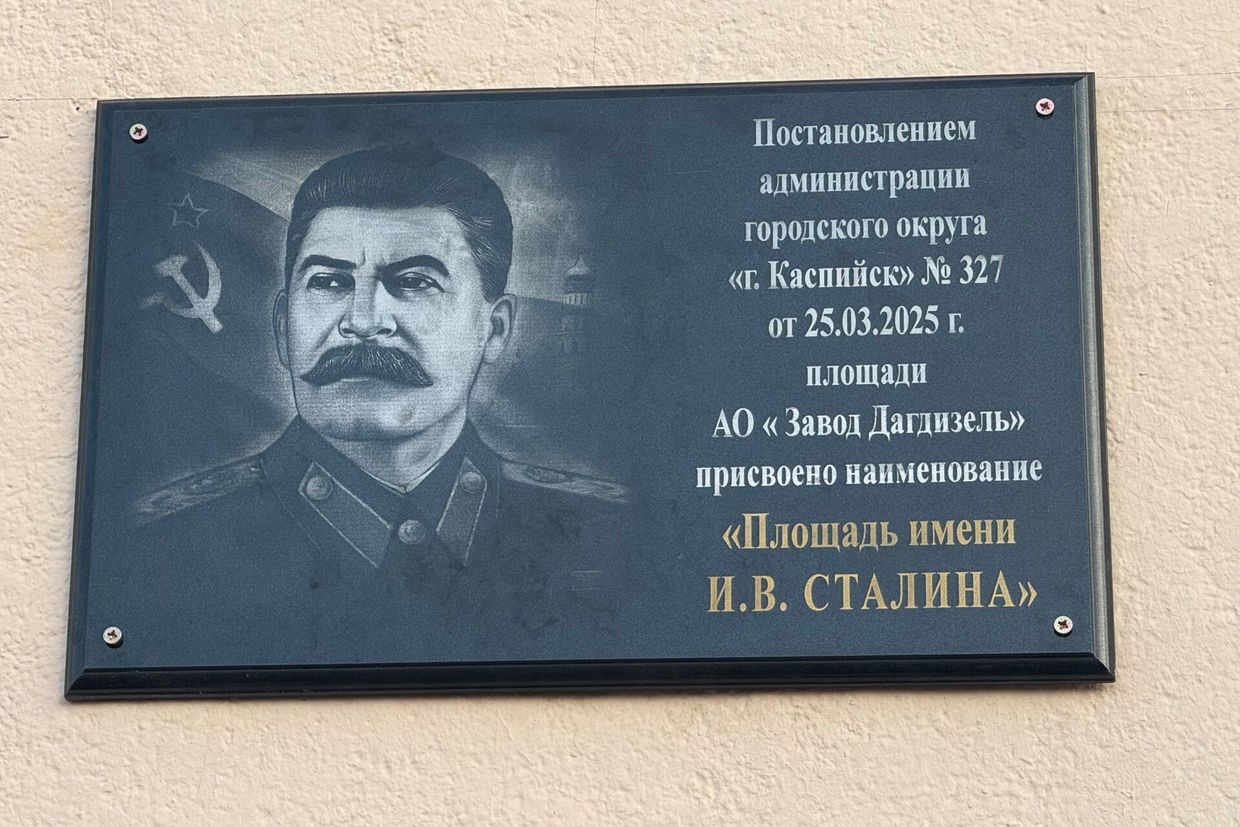

In recent years, Russia has seen an increase in the number of monuments, busts. and memorial plaques dedicated to Stalin. At present, there are no fewer than 110 monuments and memorials to Stalin in Russia, most of them installed during the presidency of Vladimir Putin. Among the regions with the highest number of such monuments are North Ossetia and Daghestan, both neighbouring Ingushetia, as well as Yakutia.