In Photos | ‘Letters to the citizens of Georgia’: the newspapers delivered by the mothers of the jailed

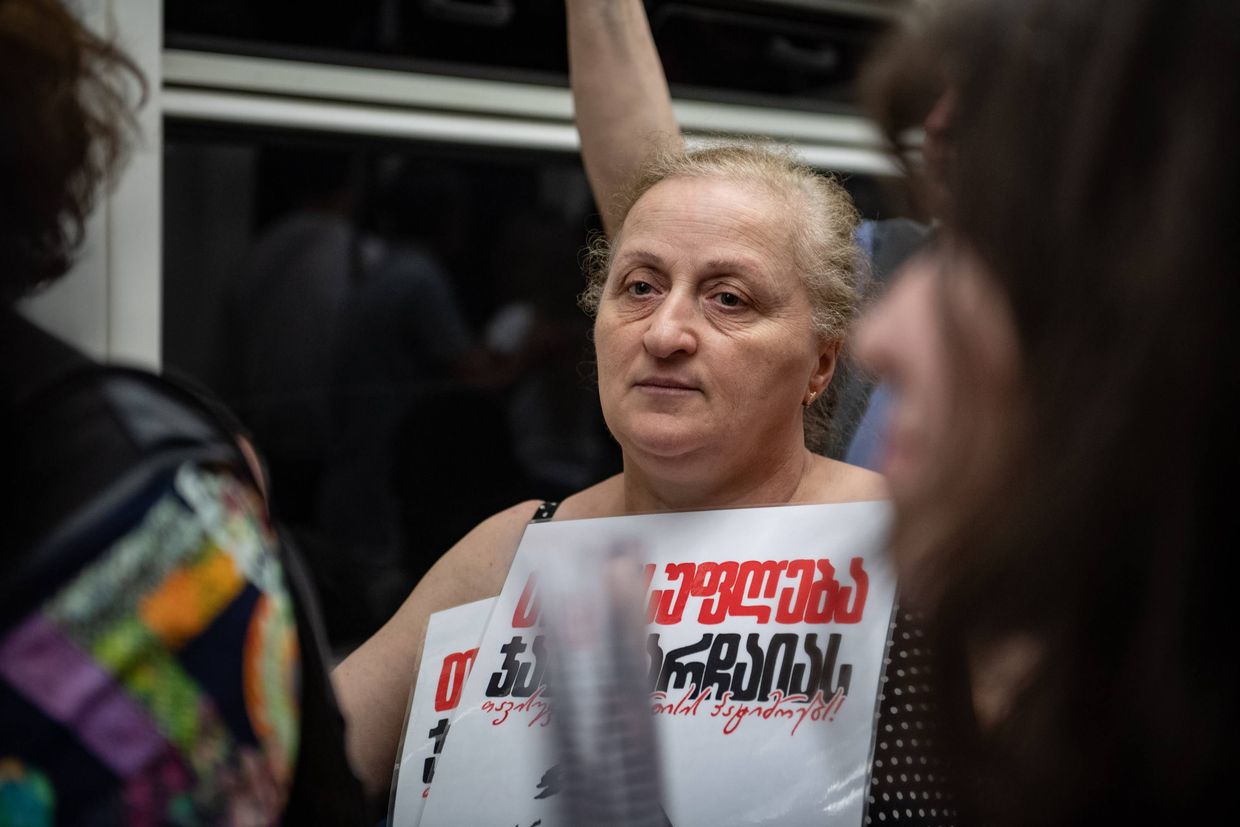

The mothers of Georgians arrested during the protests have been travelling across the country to share letters from their imprisoned children.

It all started on 31 May, when a handful of parents gathered outside the Avlabari Metro station in Tbilisi with posters of their loved ones, who are facing years behind bars after participating in Georgia’s ongoing anti-government protests.

Once assembled, they went down into the metro with a megaphone, speaking about their imprisoned relatives and the general state of democracy in Georgia.

Since then, every weekend, and sometimes up to twice a week, a group of mothers gathers to go to a new location to distribute newspapers written from inside the prisons. As of publication, they’ve distributed over 50,000 copies across Georgia during their trips.

One of the mothers, Nani Tsulaia, tells OC Media that the idea of doing something together came after she and other parents became disillusioned with the opposition, who she says did not have any ideas that could bring real results. Nani’s son, 21-year-old medical student Giorgi Mindadze, was sentenced to five years in jail in July for allegedly throwing a firework at police.

‘When we lost all hope, we, the parents, decided to unite, to hold hands and start going door to door, in the metro, in the streets — to create discomfort for everyone everywhere so that we can get our children released from prison’, she says.

Then came the idea to create a newspaper.

Earlier in the year, 19-year-old activist Zviad Tsetskhladze released a newspaper from prison called Cell 101, named after the number of his prison cell. The newspaper included his letters, an anthem, inspirational quotes, and historical facts about Georgia. Shortly after, online news outlet Batumelebi restored its print version to publish letters from imprisoned protesters.

Finally, activist Teona Chalidze decided to take the initiative — she wrote to prisoners and asked them to send her letters, using crowdfunding to put the newspaper together and print the first circulation.

Later, a second edition was made, which also included letters from the prisoners’ families. The newspaper gained its name: ‘The voice of freedom from prison — letters of political prisoners to the citizens of Georgia’.

The newspapers receive some pushback

On 3 June in Tbilisi, several of the mothers, along with a handful of activists supporting them, prepared to go to Tbilisi’s northern Gldani district.

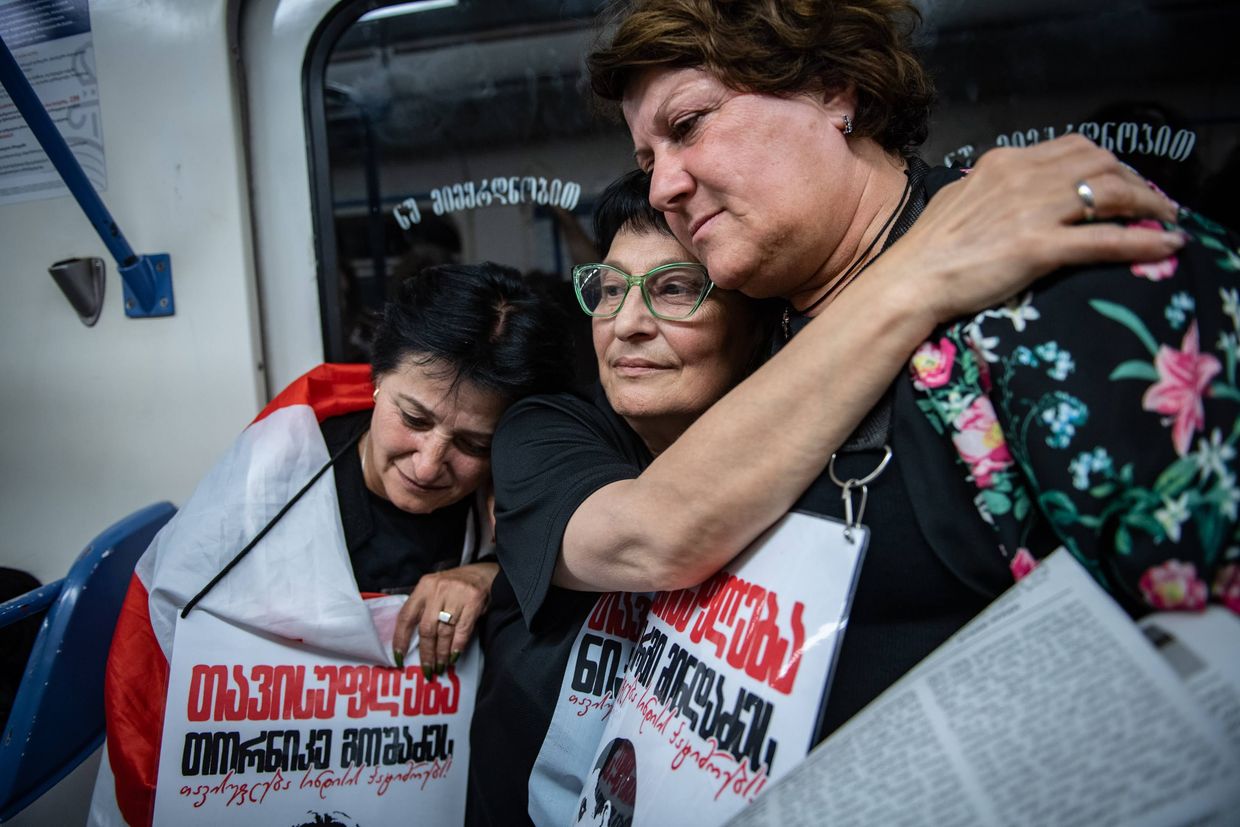

‘My beautiful one’, Nani told her friend Marizi Kobakhidze, as she tied the Georgian flag around her shoulders. Marizi’s son, Tornike Goshadze, was sentenced to two years in jail in September on charges of organising or taking part in actions that violate public order.

Once the flag was in place and the newspapers collected, they began going into the crowd, distributing the papers. But not everyone met them warmly.

Footage of another of the mothers, Marina Terishvili, being ignored by passersby as she attempted to hand out newspapers outside Akhmeteli Theatre Metro Station quickly went viral on social media. Terishvili’s son, Giorgi Terishvili was recently sentenced to two years in jail; another of her children, Mamuka Terishvili, was gunned down by a sniper during a rally in 1992.

There have been cases since when someone tore up a newspaper in front of the mothers.

Everyone has different reactions to such negative attitudes. Marizi usually enters into a full argument to explain why her son being in prison is unjust and why Georgia is going in the wrong direction. Nani, however, blesses such people, wishing them a healthy good life before moving on with tears in her eyes.

As Marizi says, if everyone was to meet them positively, they would not be in this situation today — their sons would not be in jail, and there would be no newspapers to distribute.

Even so, she says she still gets nervous when they go outside the cities to more remote areas, where Georgian Dream tends to see higher support.

‘I was so tense even when we went to Batumi’, she says. ‘But soon I realised I was wrong.’

‘We were overwhelmingly well received in [the town of] Mukhrani, for example; I didn’t expect it’, she adds.

In turn, Nani says that whenever she hands the newspaper to someone, she makes sure to look them in the eye.

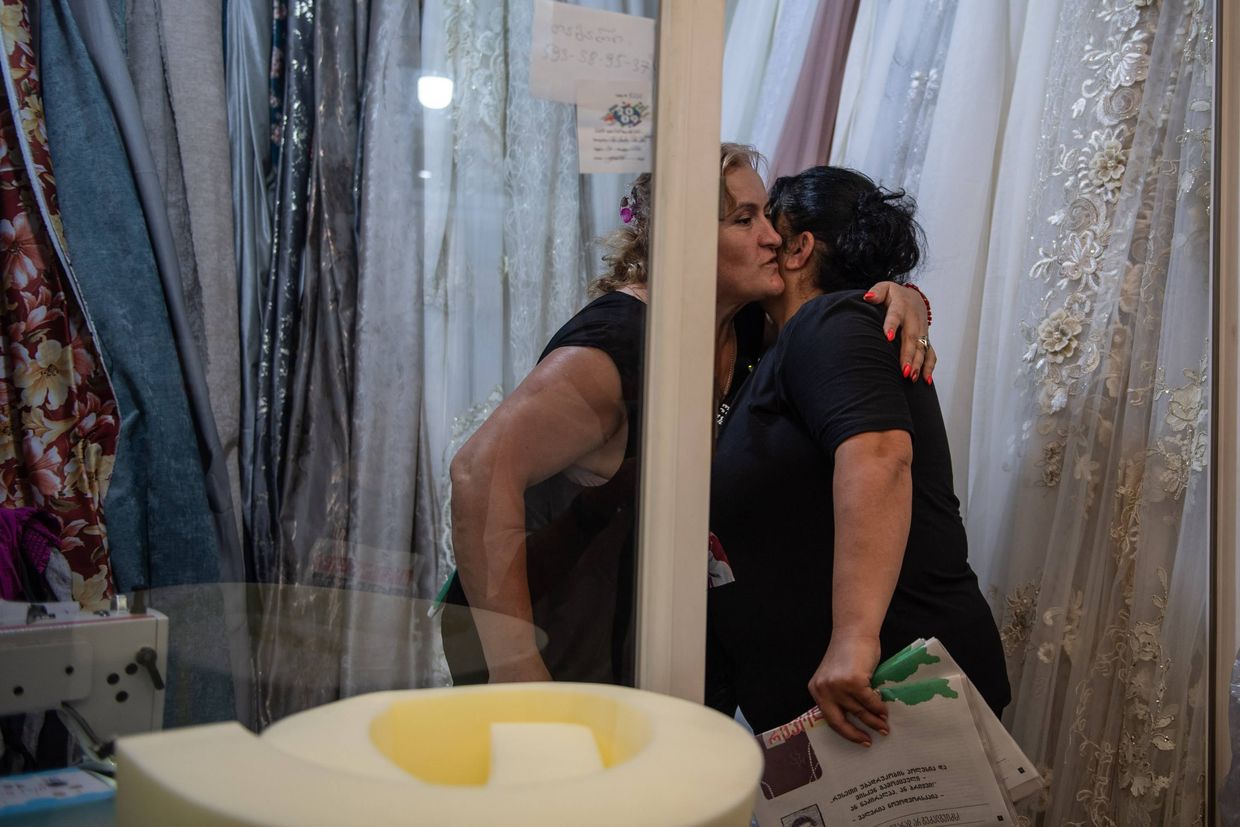

‘In most cases, I can tell from those eyes what this person wants to tell us even before they speak. When I see that they are going to speak from the heart, I open my arms and hug them, you probably have noticed this’, she says.

Nargiz Davitadze — whose son, 20-year-old Zviad Tsetskhladze, who was sentenced to 2.5 years in jail — says that in some of these encounters she sees how Georgian Dream’s propaganda works.

Nargiz remembers being hurt after a person insulted her, including references to Georgian Dream propaganda, while she distributed newspapers in her hometown of Batumi.

‘Then a second person appeared and scolded the first one, but they didn’t care and said they wouldn’t even use the newspaper as a hand fan. But usually the majority of people still meet us warmly’, she says.

Over time, their trips have become about more than distributing newspapers.

In the Pankisi Valley, for example, the mothers visited the grave of Temirlan Machalikashvili, a 19-year-old who was shot dead by Georgian security forces in 2018. His father has been seeking a proper investigation ever since then, but in vain.

They also went to the memorial of Giorgi Antsukhelidze, who fought and was killed during the August 2008 War.

On different occasions, parents and family members have gathered outside prisons for the birthdays of their imprisoned children. Similarly, they were there for each other when verdicts were announced. Sometimes, the mothers would leave the hearings of their own children to attend the verdicts of others, as the hearings would overlap.

A new family

Not everyone is supportive, however. For Nargiz, the most hurtful thing was to discover that some of those who grew up around her children, who were close, turned out to ‘prefer’ Georgian Dream’s billionaire founder Bidzina Ivanishvili to her son.

‘They don’t even write anymore, they don’t ask how [her imprisoned son] is’, she says.

Yet, as Nani says, the fact their sons were arrested brought the parents together — they’ve spent almost every day with each other since the arrests.

‘We were complete strangers to each other, but we gathered and became one big family. We all have Rustaveli Avenue and the area outside parliament to stand together and care for each other, to share sorrows from the heart. When I am tired from work, I always try to come to Rustaveli for at least an hour, because I feel relieved, because I know people will care for me there, and will say warm things about my and others’ children. Then life becomes slightly easier’, Nani says. Marina Aptsiauri is the mother of Nika Katsia, who was one of the three protesters who was acquitted by the court of drug charges. Despite her son’s release, she has continued attending the distribution trips, telling OC Media during one of these trips that she will continue to support the other mothers and fight the authorities until the last imprisoned protester is released.

‘I will never lose these new friends, never, I know it’, Nani says. ‘I can’t think of what could undo this relationship we have. If I hold a wedding for my son, I would invite these parents before anyone else […] We went through so much together.’

‘I remember my birthday, when my son was sentenced to five years in jail — that same day, we came to the parliament. Everyone was there, hugging me, comforting me, I will never forget that. People were lining up to hug me. It was a very difficult day for me, Gio’s verdict day, but these people helped me through it’, she continues.

Exploring Georgia, one paper delivery at a time

Over the summer, together with activists and volunteers, the mothers have been to over 25 locations.

‘Gio called me the other day and told me, you poor thing, if I wouldn’t have been arrested, you would have never seen anything outside Rustavi’, Nani says.

Nargizi says she didn’t have the chance to go to the Kakheti Region very often before those trips.

‘It turns out Kakheti is so pretty. I also want to visit the villages in the conflict zone’, she adds.

Nani stops her at this point, however, and tells her she doesn’t advise it, as she and Marizi went there during their trip in Samegrelo.

‘We wept so much. It is so difficult when you are a Georgian in your country, in Georgia, and there are these barbed wires installed in such a way that you don’t have the right to go beyond these wires, but beyond these wires there are those people whom you love so very much, it is very hard’, Nani says.

No matter where they go, however, they often get recognised, having become celebrities of a sort. This is usually the highlight of their day, when people remember them for their sons and for their fight for their children.

‘Everything we do, every step we take is with a goal for it to bring results tomorrow, to free our boys. Not my son or her son separately, but we will fight until everyone is free’, Nani says.

Marizi says everything she talks about, it is never about her son only but about everyone else.

‘We are proud of our sons. It is so hard when you wake up and he is not at home. You put your hand to your heart for it not to stop beating and then you get up knowing that you have to continue fighting’, Marizi says.

Nani says they don’t know what the future will bring, but they won’t stop.

‘I don’t know how much time it will take, but everyone will be released soon and the kindness will return to Georgia. We will have such a day one day. Then we once again will gather on Rustaveli, mothers with sons, to celebrate’.