Opinion | Chechen women are speaking up, but is anybody listening?

Though small, the first all-women Chechen March highlights how Chechen women are forced to live at the intersection of Islamophobia and xenophobia, leaving their struggle often all too invisible to the larger international community.

Let’s make it clear: Chechen women have never been completely estranged from politics.

In the 19th century, during the Russian-Chechen war, Chechen military leader Taimaskha Gehinskaya was famous for her bravery, even among her enemies.

During both Russian-Chechen wars, some women fought alongside men, providing medical assistance to resistance fighters, working in the media, and protecting young Chechen boys from Russian soldiers.

In Ukraine, one of the ideological leaders of Chechen pro-Ukrainian battalions and a prominent Chechen EuroMaidan activist was a woman, Amina Okueva.

Yet, on the international level, Chechen women today remain invisible, almost completely erased from any international discussions about the situation in modern-day Chechnya. The vital civil rights principle ‘nothing about us without us’ just doesn’t seem to apply.

A Chechen woman’s story is not something you are likely to find in your local bookshop. Any stories that do appear were likely written by ‘experts’ who do not know Chechen or any other North Caucasian languages and who use primarily Russian sources, despite the fact that many in Russia, even among the so-called ‘liberal opposition’ show some Islamophobic and xenophobic tendencies towards Chechens.

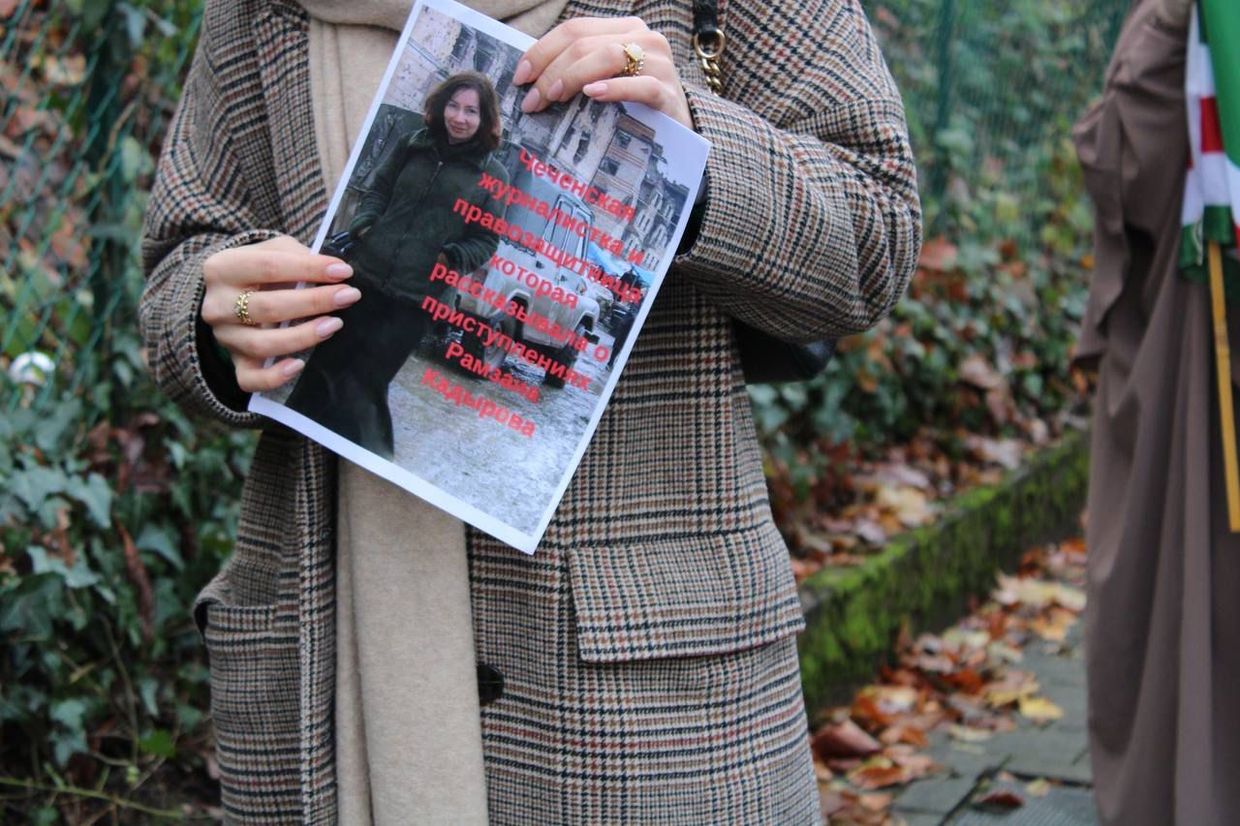

Given all of this, the first all-women Chechen March which took place in front of the Russian Embassy in Brussels on 7 December, dedicated to the persecution of Chechen women by Chechen head Ramzan Kadyrov, was extremely exciting, though it too highlighted the invisibility of Chechen women within the greater international community.

‘No one listens to actual Chechen people’

Sofia, a 23-year-old Chechen activist from Brussels and the main organiser and ideologist of this demonstration, told me ahead of time that she expected 20 or so women to come, including religious women who wouldn’t participate in mixed demonstrations.

She emphasised that the demonstration was meant to avoid being directed towards one political position or party in an effort to welcome more participants.

Currently, there are three different political groups who call themselves the Chechen ‘government in exile’, in addition to other various political entities and movements which act independently.

‘I refuse to connect [the march] to a specific organisation or group. Everyone who is ready to speak up against the actions of the Russian administration of Ramzan Kadyrov and all the crimes they committed against Chechen women is welcome’, she said, noting that she wanted to see women from other diasporas, as well as local Belgian women, join them as well.

However, even 20 people is an ambitious number for a modern Chechen protest in Europe. Generally, the Chechen diaspora is not very keen on showing social solidarity offline, frightened of possible persecutions of their family members back home.

Following the pattern, only seven women attended the demonstration in the end.

‘I feel disappointed’, Sofia told me. ‘If we don’t speak up against oppression back home, nothing will change’.

However, Sofia still believed that holding the march was a good step forward for future development.

For one, it helped to make the life of Chechen women refugees more visible for both European authorities and police.

‘The police were extremely friendly, protecting us from a possible provocation’, Sofia said.

In addition, the demonstration made Chechen women more visible to media, which were interested in the event, creating a larger audience who could learn about the persecution of Chechen women by the Kadyrov regime.

Fatima Suleimanova, a 28-year-old Chechen student at the Sorbonne in Paris and the first and only Chechen woman to have spoken at the Council of Europe, helped with organising the event and dealing with media interviews. She pointed out during the march that it was important to discuss such persecution not just in Chechen and Russian, but also in French, to reach the local Belgian audience and the media.

‘I pointed out in my speech that Chechen women were persecuted not by the “Chechen authoritarian regime”, but by Russian puppets. The only reason why Chechen women are persecuted now is Russian occupation. No one listens to actual Chechen people, both male and female, because we live under occupation. The West needs to follow the example of Ukraine and recognize Ichkeria as an occupying territory’, Suleimanova said.

When Russia occupied Chechnya with the approval of the international community, Russia also took control of the narrative. By recognising that Chechnya is the inner business of Russia, Western — and Eastern — politicians also recognised that Russians know better who Chechen are, and that Russians know ‘more’ about the role of Chechen women in Chechen society then Chechens themselves.

Zarema Musaeva and the liberation of Chechen women

Emphasising the diversity among Chechen women, Sofia, unlike Suleimanova, is not into politics.

‘I do not see myself as a politician figure’, Sofia told me. ‘I’m just standing up against injustice. I think we all should. When Zarema Musaeva, a woman who suffers from diabetes and who, like we all believed, could see her children very soon, got another fake political criminal case, I was outraged. In Chechen culture, and in Islam, women shouldn’t be treated that way. In the past, when Chechnya was independent, women were never punished for what their male relatives did or used as bait. It has always been a great taboo, and only Russian occupation broke it’.

In January 2022, armed men, part of Kadyrov’s administration forces, broke into Zarema Musaeva’s apartment in Nizhniy Novgorod, in Central Russia. They dragged Musaeva from the flat and drove her all the way back to Chechnya, where she was charged with ‘petty hooliganism’, receiving a sentence of 15 days in prison. It was obvious that the case was purely political, and that she was targeted due to the oppositional activism of her sons, Ibragim and Abubakr Yangulbaev.

According to Amnesty International, the following day, Kadyrov issued death threats against the Yangulbaev family.

Zarema Musaeva has remained in prison ever since on various trumped up charges. In November of this year, Russian authorities opened a new criminal case against Musaeva, accusing her of ‘assaulting’ a prison guard.

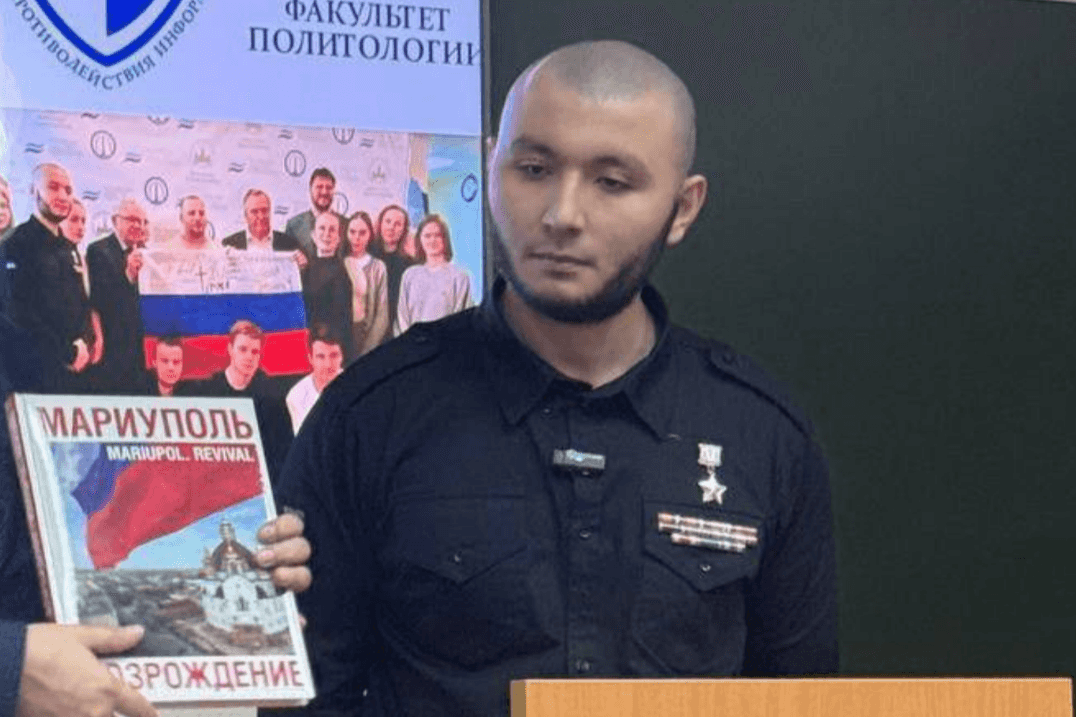

This objectification and violence against women is something new, Ibragim Yangulbaev, one of Zarema Musaeva’s sons and one of the leaders of the Chechen opposition channel 1Adat, told me.

‘Before my mother was kidnapped, many Chechens couldn’t imagine that something like this was possible. The violence against female relatives of Chechen leaders like Aslan Mashadov and Abdul Hakim Sadulaev wasn’t well-known to the general public, and it wasn’t done so openly. When my mum was kidnapped and imprisoned by a fake case, everyone knew it. It had been done so openly. But we can’t say how many other women have been imprisoned in a similar way’, Yangulbaev said.

According to Yangulbaev, his mother was never a political activist, but she supported him when he was kidnapped by Kadyrov’s authorities for his political actions.

He added that when Sofia and other organisers came and asked for his permission to hold a demonstration to raise awareness of Zarema Musaeva’s case, he gave them his full support.

‘I support women to speak up about crimes committed against them. We will be near to protect them against provocations, but they will speak and organise everything by themselves’, he told me, noting that mixed-sex demonstrations could make some women feel uncomfortable.

Yangulbaev also highlighted that his mother needed any and all the support she could get, as her diabetes worsens every day.

There are no clear statistics regarding how many other women are currently locked up in Kadyrov’s prisons, where conditions resemble concentration camps. The Russian administration in Chechnya was never good at recording accurate numbers, but a new policy under Kadyrov to punish Chechen dissidents, supporters of Chechen independence, and those who support Ukraine and who oppose Russian President Vladimir Putin by targeting their female relatives has created a whole new issue regarding record-keeping.

Why are Chechen women still invisible?

According to Suleimanova and Sofia, Zarema Musaeva was able to become a symbol of injustice against Chechen women because 1Adat was a popular Telegram channel and social movement. I believe that it has also helped that she is a mother being punished for not betraying her children — an image that can create a lot of empathy.

But she is not the first prominent victim of the Russian regime in Chechnya.

In 2009, Russian forces in Chechnya kidnapped and murdered famous Chechen human rights activist Natalia Estimirova. This case received public attention in the West, but even English-language Wikipedia and left-wing media like the Guardian labelled Natalia as a ‘Russian activist’, erasing her identity as well as the four hundred years of anti-colonial fighting that her nation had waged against Russians. Her story instead was told using the typical stereotypes that exist in Russia about Chechens.

In 2022, Romania tried to deport a Ukrainian refugee of Chechen origin, Amina Gerihanova, after Russia accused her of being a terrorist supporter. The woman was separated from her son and imprisoned despite the Ukrainian Security Service proving her innocence. Dozens of demonstrations were held in different European countries, including the UK, France, Austria and Germany. Amnesty International got involved as well, eventually leading to her release.

Yet, despite the fact these cases were all quite prominent, Russian women showed indifference to the fate of their Northern Caucasian sisters.

Having been involved in women’s rights activism from 2015-2018 in Saint Petersburg, I can say that most Russian liberals and leftists don’t differ much from Russian conservatives in their views on North Caucasian women.

In general, Russian liberals do not like to speak about colonial politics in Chechnya, or respect Chechen national identity. While there were once a few exceptions, such as the late Russian dissident Valeria Novodvorskya or the late Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, today, in the time of social media, the struggles of Chechen women largely go ignored.

Russian activists are only interested in cases where North Caucasian women were arrested for being openly queer, making body-positive pictures, ‘spreading hatred’ toward men, or at least being victims of domestic violence, not when such women are persecuted because of their ethnic and religious beliefs.

In most Russian-language women’s rights discussions, the topic of intersectionality, linking xenophobia, racism, and sexism, is considered to be something only related to Black women in the US, not something that is also found in Russia, a belief which stems from the Soviet tendency to pay more attention to international problems and ‘criticise the West’. By turning a blind eye to intersectionality, Russian women perpetuate the classic colonial feminism and White, Christian saviour complex that was once the mainstream within Western liberal discourse.

Most post-Soviet feminists, liberals, and women’s rights activists also stay beholden to orientalist stereotypes, wherein Islam is viewed as an extremely misogynistic religion. Negating the facts on the ground, Russian activists deny Muslim women, including those in Chechnya, of their agency.

Sofia told me that when she was coming up with her idea for a demonstration, she faced hatred from a woman in one of the Russian-language opposition channels on Telegram, who could not believe that Chechen women would go to such a march on their own volition. According to this woman, who works with refugees, Chechen women were being forced to go to such marches by Chechen men.

This is an Islamophobic and xenophobic stereotype whereby the lives and agendas of actual Chechen people are ignored. And in turn, their stories become misrepresented among the international community.

This is why events like the all-women Chechen march are extremely important. Such demonstrations show that Chechen women are finally ready to speak up for themselves and challenge Russian propaganda and Western stereotypes.

Chechen women are speaking for themselves, and as social tendencies are showing, they are going to keep speaking up in the future — you just need to listen.