Opinion | How Azerbaijan’s pro-government media is shifting the security narrative

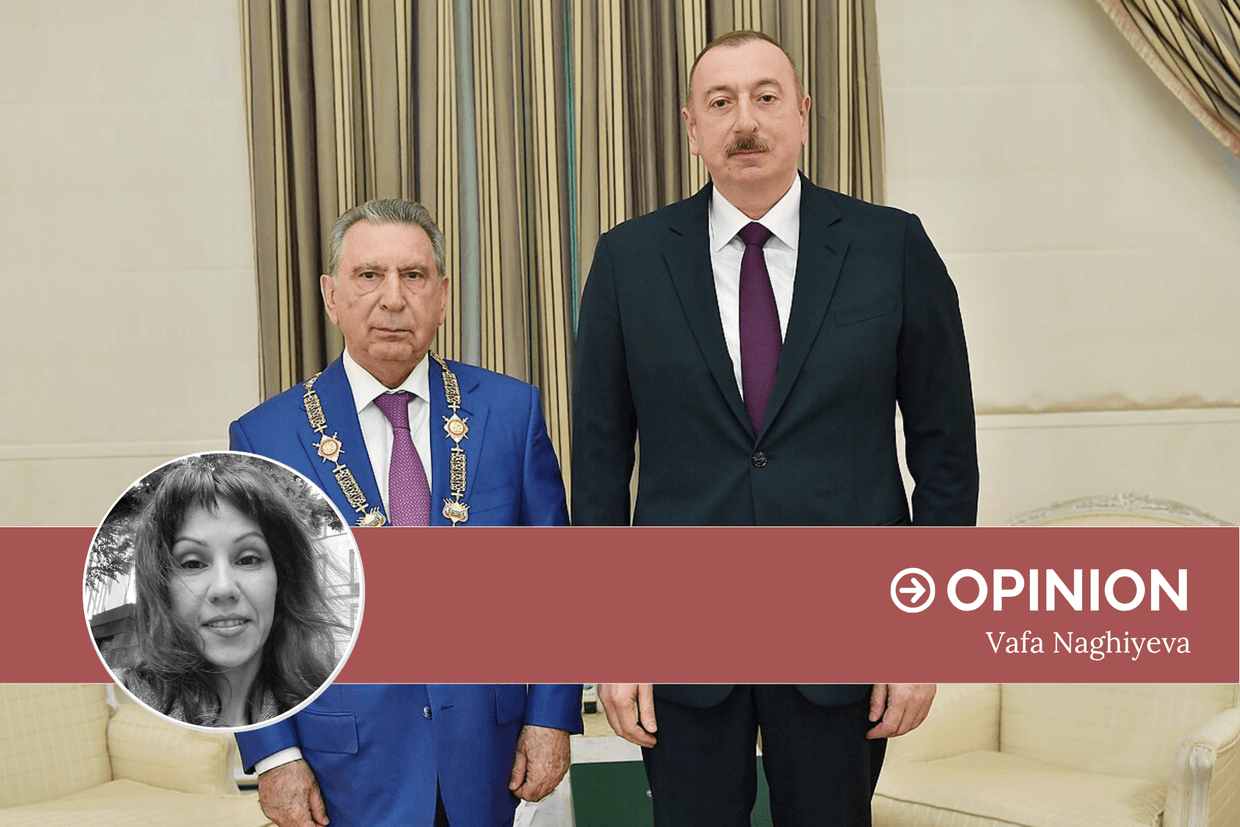

The downfall of former Presidential Administration Head Ramiz Mehdiyev is the perfect example of authoritarian information control.

From 14–15 October, the main news in all Azerbaijani pro-government media outlets was the pre-trial detention measure ordered against former head of the Presidential Administration, Ramiz Mehdiyev. He had been charged with high treason, seizure or retention of power by force, and the legalisation of criminally obtained funds.

For over two decades, Mehdiyev served as the ideological backbone of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian governance. He was regarded as one of the main architects of the political transition that secured the transfer of power from former President Heydar Aliyev to his son, Ilham Aliyev, in 2003. As the head of the Presidential Administration (1994–2019), he helped consolidate the power structure that sustained Ilham Aliyev’s rule.

Yet in October 2025, the same system that he helped construct turned its full propaganda machinery against him. In the absence of independent journalism, state-aligned outlets tell the public not only what happened, but how to think about what happened. The case of Mehdiyev, therefore, offers a rare glimpse into how narratives are engineered, synchronised, and reoriented to serve the changing political needs of power.

Immediately after the news broke, government-aligned information channels launched a mass media campaign targeting Mehdiyev. Almost every day, new ‘details’, ‘sources’, and ‘revelations’ about Mehdiyev appeared in the press. Indeed, between 15–18 October, Modern.az, one of the main propaganda outlets in Azerbaijan, published 36 articles about Mehdiyev; Qafqazinfo.az released 22, and Report.az five.

Such representation bore all the marks of a centrally coordinated information operation. The repetition of identical headlines, rhetoric, and phrasing across outlets suggests that Mehdiyev’s image as a ‘traitor’ was not reported, but rather carefully manufactured and constructed over just a few days through systematic media framing.

From the very first headlines, pro-government media established a moral binary of loyalty versus betrayal. Mehdiyev was portrayed as someone who had ‘sold out the state’ and ‘worked with foreign powers’. The recurring use of emotionally loaded terms such as ‘treason’, ‘network’, ‘foreign intelligence’, and ‘shadow plan’ created an atmosphere of urgency and moral outrage, transforming a legal case into an existential threat to the nation. Beyond individual portrayal, the broader narrative served a political function.

By framing Mehdiyev’s downfall as a national cleansing, pro-government media reproduced one of the key techniques of authoritarian information control — the creation of a controlled crisis. Each new ‘enemy within’ renews the moral energy of the regime and sustains the illusion of permanent vigilance. It is no coincidence that, in the days following Mehdiyev’s arrest, members of parliament rushed to demonstrate their loyalty publicly. Declaring distance from him became almost a political ritual, a symbolic act of purification.

One of the most striking examples came from Zahid Oruc, a long-time pro-government MP who had previously referred to Mehdiyev as his ‘father’. In a post on Facebook, Oruc confessed that he had once addressed Mehdiyev with that term ‘in front of several colleagues’ and that ‘he was closer to us than our own fathers’. He then dramatically added, ‘Now, hearing what he has done, I am horrified. Therefore, I sincerely apologise to our real father, President Ilham Aliyev’.

Such gestures illustrate how loyalty in Azerbaijan’s political culture operates not as an ideological commitment but as a performative display. Public contrition functions as a demonstration of obedience; the narrative of betrayal is completed only when the elite reaffirms its submission. In this way, the regime transforms individual scandals into collective loyalty rituals, acts through which power reasserts itself as both moral and paternal.

Another striking example of the narrative engineering around Mehdiyev concerns the Azerbaijan Airlines (AZAL) plane crash in Aktau, Kazakhstan in December 2024.

Over the past year, pro-government media has consistently blamed the crash on Russia, and even Russian President Vladimir Putin personally. Yet now, the same media outlets claim that Mehdiyev was behind the crash, and that it was part of a broader coup scenario.

The turning point came after a private meeting between Aliyev and Putin in Dushanbe on 10 October. Within days, the framing of events changed dramatically and the once-hostile rhetoric toward Russia vanished. Instead of portraying Moscow as responsible, the press began describing Putin as ‘a friend of Azerbaijan’, while accusing Mehdiyev of ‘attempting to damage bilateral relations’.

This reversal was not an isolated case. In June, when two Azerbaijani brothers were killed by police in Yekaterinburg, Azerbaijani media launched an aggressive anti-Russian campaign. Outlets such as Report.az used phrases like ‘ethnic cleansing’, ‘a crime against our nation’, and ‘Putin’s fascism’.

Between 27–30 June, Report.az alone published 86 news items about the case. Yet when I checked again on 18 October, I found that more than half of those articles had been deleted, leaving only 33 online.

This systematic erasure of content demonstrates not just censorship but a strategic recalibration of narratives. When foreign policy priorities shift, the media apparatus swiftly rewrites collective memory, deleting yesterday’s ‘truths’ to make room for today’s political needs.

What is happening to Mehdiyev today is less a judicial process than a media performance. Over the past week, pro-government outlets have flooded the public sphere with stories, speculations, and moral condemnations, creating the illusion of transparency while in fact concealing the truth. We are not witnessing information; we are witnessing a carefully staged information storm.

It is possible that Mehdiyev’s prosecution is being used to pin the entire rupture in Azerbaijan–Russia relations on a single man. In this version of the story, the government sacrifices a long-time loyalist to repair its image abroad while projecting strength at home. Whether this ‘treason’ narrative serves that purpose, or conceals something deeper, remains to be seen.

In the absence of independent journalism, Azerbaijan’s state-aligned media does not report what is happening — it decides what can be seen. The endless repetition of identical headlines gives the impression of knowledge, yet it hides more than it reveals.

Mehdiyev, now 87, has been transformed from the regime’s ideologue into a national traitor overnight. Tomorrow, or perhaps in five months, the same outlets may quietly delete these stories, just as they erased their previous attacks on Russia.

The lesson is clear, in Azerbaijan’s media ecosystem, narratives are temporary, but control is permanent. Each wave of outrage, each ‘enemy of the state’, serves to reaffirm the power that produces them. What we see today is not a transparent account of events but a state-orchestrated spectacle, a mirror reflecting only what the government wishes the public to see.