Opinion | The Velvet illusion: why Armenia’s so-called revolution wasn’t

While the Velvet Revolution was indeed a strong example of people’s resistance, it failed to confront the deeper architecture of Armenian politics.

On 23 April 2018, I was hit hard by the Madrid sun, along with the sweet taste of Spanish sangria, and the bittersweet taste of revolution in Armenia.

I was living abroad for the first time, volunteering in Spain. It was a surreal experience, being able to travel freely. It also provided a much-needed break from Armenia. After years of burnout from street activism and journalism, I needed distance.

Then the call came: ‘Have you read the news? [Then Prime Minister] Serzh Sargsyan has resigned’.

Suddenly, I was gripped by FOMO — the protests in Yerevan now seemed sweeter than the sangria in Spain.

The protests mobilised a broad part of society and showcased the power of people’s resistance. They carried the hope of ending Armenia’s corrupt and criminal past — yet in the end, expectations that the right leader with the right government would choose the right path for the country and its people turned out to be false.

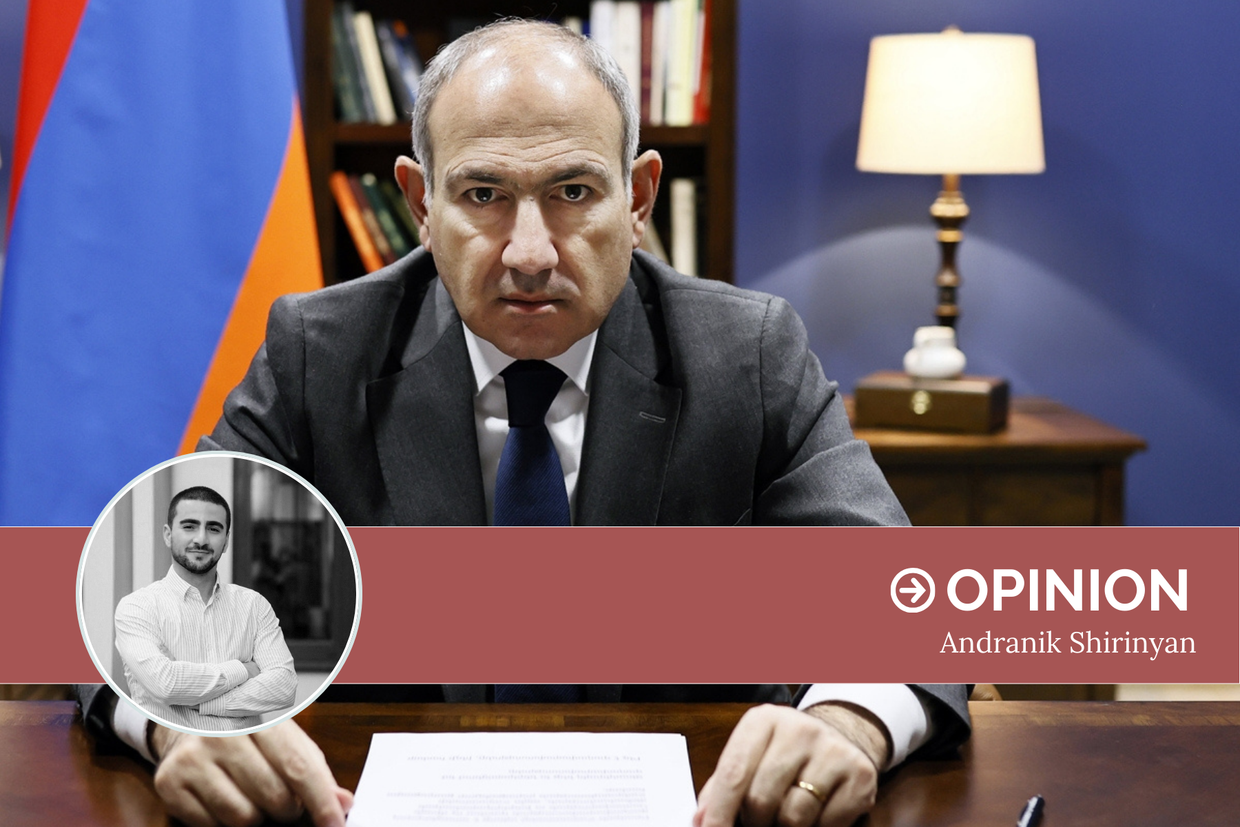

While on the streets during protests, Nikol Pashinyan promised us justice, freedom, and democracy, and then, behind the gates of the parliament, and later, on Instagram, demonstrated the opposite.

The protests that brought down Sargsyan were a remarkable civic moment in Armenia. However, we should stop pretending that it was a revolution.

The Velvet Revolution was a turning point that was quickly stolen and sold back to the people as democracy. It was a regime swap dressed in revolutionary clothing; the old machine didn’t break, just rebranded. It was more of a velvet curtain, a soft cover for the continuation of the past.

In fact, calling the Velvet Revolution a ‘revolution’ may be a part of the problem, since it allows both domestic and international actors to overstate progress to their benefit. It helps to maintain the illusion that systemic change is possible within the existing order. It teaches us that all we need is a new leader, a clean election, and a rebrand, and everything will change. But this kind of revolution only serves those who end up stealing, or helping others to steal, the country’s resources. This kind of revolution only serves reformists who, in the name of revolution and elections, sell us the idea of the nation-state to secure and corrupt power.

What happened in Armenia was an impressive civic uprising, but it left the skeleton of the old state intact. The economic model, rooted in neoliberal dependency and privatised wealth, was not only preserved but reaffirmed to privilege private capital and foreign investment over social justice.

True revolution begins with the awareness that systems of exploitation will keep reproducing as long as we allow ourselves to be dominated by pre-prescribed powers; those who have long proven they do not share our interests.

The Velvet Revolution was nationalist, reformist, and middle and upper class in character, and thus, it was system-preserving at its core. A revolution should be intersectional, dismantling the deep power structures embedded in the state. It should abolish or at least reduce sexism, patriarchy, militarism, and hierarchies of power between us. A real revolution is about building institutions that serve the people, not those who rule them. Otherwise, we will repeat the same mistakes again and again.

And yet, the myth of the revolution persists. It is convenient for liberal NGOs, for Western diplomats, for some disillusioned Armenians desperate for hope, who think that the liberal democracy of Armenia is enough of a change. But myths are dangerous as they mask reality. What happened in Armenia was not a revolution; it was a managed transition that served the interests of a new political class while preserving the norms of the old regime. If we keep calling it a revolution, we’re helping cover up that lie.

The political elite still governs with minimal accountability. And what about us? We are increasingly alienated from the entire idea of change since we are in a loop of repeating old problems in new forms. Despite the recent ‘Europeanisation’ of Armenia — with the taste of fruity sangria and democracy overtaking the political landscape and creating the illusion of a better life — under the pressures of war, geopolitical instability, and high inflation, the standard of living continues to decay.

The new ruling class under Pashinyan didn’t dismantle the architecture of oppression — they took up the very same seat. Pashinyan quickly became more focused on preserving state legitimacy than fulfilling the aspirations of the people who put him in power. New elites replaced the old ones without changing the systems that enabled corruption and unaccountability in the first place.

Pashinyan and his team hung a velvet curtain over the country’s corruption, cutting it at the lower levels to improve Armenia’s ranking on the Corruption Perceptions Index, plateauing there, and then shifting that corruption to higher levels.

After 2020, Pashinyan’s government kept using nationalism to justify its unaccountability regarding Armenia’s loss in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, including calling on the Armenian people to become the country’s saviours again and again, as if it was not the government’s ‘role’.

‘The homeland is the state. Do you love your homeland? Strengthen your state’, he said. Sound familiar? That’s the old regime in new clothes.

The problem isn’t the individual, it’s the concept. The belief that any leader and their party can deliver the reforms we deserve is a delusion. Yet, the majority still clings to this idea, just like the reformist populists from Pashinyan’s team, who pretend to be rebuilding Armenia but can’t even deliver a functioning public transportation system in the capital. The ‘developing’ transport network is a clear metaphor for the Armenian state: it exists, but you'd better not rely on it.

Many grassroots activists joined Pashinyan’s team after the Velvet Revolution and quickly got absorbed into the system, reproducing the old with new aesthetics. Instead of creating alternative forms of living, they chose the state, the very structure they once fought against. This proves there can be no just transformation without systemic change. The opposition Pashinyan would hate the leader Pashinyan.

Today, Armenia’s ‘opposition’ is made up of people who previously ruled the country or were closely tied to those in power. The political field is reduced to a binary: ‘the old regime’ vs. Pashinyan. There are no real alternatives, only a choice between the bad and the worst leaders and parties.

The growing discourse ‘maybe the previous government wasn’t that bad’ proves that our collective understanding of change is still tied to having the ‘right’ leader. This is how revolutions are co-opted by elites, who enjoy the ride while it lasts. We cannot forget: no bad leader can justify the crimes of the previous regime.

Take Levon Kocharyan, the son of Robert Kocharyan, who brings up the pregnant woman who was killed by Pashinyan’s convoy to criticise his democracy. In turn, Pashinyan claps back, reminding how Robert Kocharyan’s bodyguards killed Poghos Poghosyan in the toilet of a cafe for saying ‘Privet Rob’.

People should not be stuck choosing between killers, whether systematic or accidental. But until we reject leadership as the core of change, this is the choice we are going to be left with: choose your killer.

Once again, the problem is not who governs or who will. In the system of the nation-state, power always corrupts, and the people’s needs are diminished. Until we understand this, we must stop confusing mass mobilisation and regime change with revolution. We must learn to call illusion by its name — or we will keep mistaking the velvet glove for revolution.

The Velvet Revolution was a strong moment of people’s resistance. However, until the deeper architecture of Armenia’s political economy and structure is not confronted, the revolution remains unfinished. Or perhaps, for the sake of feeling closure about my Spanish FOMO, we can say it never truly began.