Opinion | Why the arrest of women journalists in Azerbaijan is a feminist issue

By weaponising gender, the Azerbaijani authorities redraw the boundaries of who is allowed to speak.

In 2023, Azerbaijan turned criminal law into a tool against independent reporting. It began with a raid on the offices of Abzas Media, during which the authorities claimed to have discovered €40,000 ($46,000) in cash — soon after, editor-in-chief Sevinj Abbasova (Vagifgizi) was arrested along with her colleagues. The same playbook soon reached Toplum TV and Meydan TV, with coordinated searches and arrests that folded more newsrooms into a single criminal narrative.

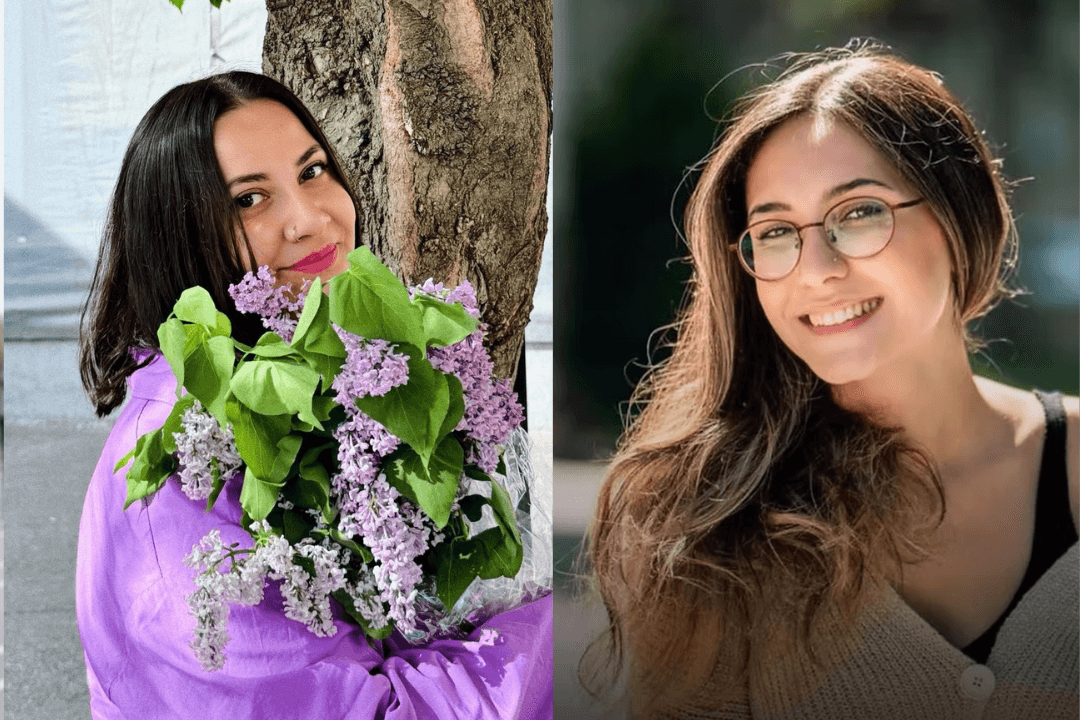

By May 2025, nine women journalists were jailed on economic charges that were flexibly applied in order to prosecute — these included currency smuggling, illegal entrepreneurship, and money laundering. The nine women journalists include Vagifgizi as well as Nargiz Absalamova and Elnara Gasimova of Abzas Media; Aynur Elgunash, Aytaj Ahmadova, Aysel Umudova, and Khayala Aghayeva of Meydan TV; the freelance reporter Fatima Movlamli; and Ulviyya Ali, a Voice of America contributor, who was arrested as part of the Meydan TV case.

This crackdown isn’t gender-neutral. Women reporters in Azerbaijan have long been subjected to gender-based smear campaigns, online trolling, and threats intended to shame them into silence. In many cases, they have also faced physical violence while doing their jobs, as well as slut-shaming in state-aligned media and on social platforms designed to degrade and discredit them. The current wave simply weaponises the criminal code to finish the job: removing women from public life precisely because they are public. That is why the fate of these nine journalists is not only a press-freedom emergency; it is a feminist one.

Until the mass crackdown that began in late 2023, arrests of publicly active women in Azerbaijan were relatively rare. Public debate often traced this to patriarchal rules that prescribe a different, ‘lighter’ treatment of women in public life, wherein the state tolerated politically active women for optics and convention, as well as simply underestimating women’s political power.

Indeed, before police cells and courtrooms, many of these women had to win a quieter fight, waged within their own families. Patriarchal rules cast a woman’s independence as a threat, so choosing journalism meant arguments, disapproval, and moralising.

As Nargiz Absalamova noted in court, even from detention she still hears relatives saying her family should have stopped her becoming a journalist. In a letter from prison, Aynur Elgunash recalled bringing home her first passport and saying ‘from today I am independent’, only to be scolded that a girl must not claim independence because ‘independence’ leads to a bad path.

The message is the same in both stories: a woman who insists on public agency risks shame and punishment. The current criminal cases are the state’s extension of that discipline.

This same policing applies to women’s marital choices — women routinely face social and familial pressure over when and whom to marry, and early and forced marriages overwhelmingly harm women and girls.

Notably, investigators have attempted to prevent Aytaj Ahmadova from registering her marriage, despite this move appearing to contradict Azerbaijan’s official ‘family values’ rhetoric.

Deciding if and when to marry is part of intimate autonomy, protected under local and international human rights law. When the state inserts itself into that decision during detention, it casts itself in a patriarchal ‘father’ role and makes explicit the carceral state’s paternalistic ambition to regulate women’s private lives. The message to detained women is blunt: even your most personal decisions are subject to control.

Yet despite these patriarchal views, by criminalising these women’s work, the authorities have effectively acknowledged that women are serious political actors whose reporting can challenge the current order.

These journalists have consistently covered those pushed to the margins, producing substantial reporting on gender and queer life, from investigations to features and field reports. Aysel Umudova and Ulviyya Ali were recognised by the Queeradar initiative for reporting on queer issues; Nargiz Absalamova and Fatima Movlamli produced works for the feminist YouTube channel Fem‑Utopia.

Their detention, therefore, is an attempt to block more than individual careers; it dims one of the few remaining spotlights on gender-based discrimination and violence in Azerbaijan. Silencing those who report on marginalised groups silences those groups themselves.

Even behind bars, however, women journalists continue to report. From letters and collective statements, they are documenting the conditions faced by women in detention: shortages of sanitary products and basic supplies, degrading treatment, the specific hardships of pregnant and caregiving women, and physical and psychological abuse. They also speak of their own experiences.

When Aytaj Ahmadova was arrested, personal photographs from her devices were seized and circulated in pro-government media to shame and discredit her. According to her account, Ulviyya Ali was twice threatened with rape by police officers to force her to unlock her devices. Likewise, Elnara Gasimova was reportedly held under constant video surveillance in the Khatai District Temporary Detention Facility and compelled to change clothes in view of cameras.

In a recent letter from prison, Gasimova expanded on the differences in treatment between men and women prisoners, highlighting in particular the control over women’s clothing. Another example she gave was how women’s love letters, if obtained by the prison administration, were read aloud publicly in order to humiliate them.

These are not bureaucratic excesses; they are forms of gender-based violence. Crucially, the ‘punishment’ does not end with fabricated charges and detention; their identity as women is used as an additional lever of coercion, with gender itself weaponised to intensify pressure and harm.

Because reliable information about women in prisons is scarce, their writing has been one of the first sustained public records of these realities — an act of journalism that challenges the opacity of carceral institutions and the gendered harms within them.

There is one more piece to the story. After high‑profile arrests, state‑aligned outlets routinely push stories designed to erode public sympathy. In the cases of the women journalists, propaganda focused on their participation in feminist protests and the slogans they carried, using conservative moral panic to frame feminism as a threat.

On the day she was summoned to the Baku City Main Police Department, Elnara Gasimova marked her defiance with bright red lipstick, a locally understood sign of feminist resistance. Nargiz Absalamova and Ulviyya Ali have continued to appear at court hearings and investigator meetings wearing the same red shade, signalling that the struggle endures even under detention. At one hearing, Aytaj Tapdig carried bell hooks’ Feminism Is for Everybody, signalling that her case belongs to a global tradition of feminist resistance.

These gestures matter: they reveal the gendered core of the campaign and stake a clear claim to women’s presence in public life. These women are not only journalists under pressure; they are feminists who choose to resist visibly.

When the state authority itself labels these women ‘feminists’ to mobilise stigma and justify an unlawful punishment, it confirms the gendered nature of the repression. If the state insists the problem is their feminism, then this is unavoidably a feminist issue.

Framing these arrests solely as a press‑freedom crisis misses what is specific about the targets. The women detained are not incidental to the story; they are central to a wider project of disciplining women who speak, organise, and investigate. Treating women journalists as security risks because they are visible, outspoken, and effective reflects a patriarchal logic: it chills women’s participation in journalism and narrows who counts as a legitimate public voice.

Beyond individual pain, these cases trigger a systemic chilling effect. Women journalists considering investigations into gender‑based violence, reproductive health, or queer life now see the costs as potentially carceral, accompanied by sexualised smears and doxxing. The effect is discriminatory: it deters women and queer‑affirming voices from public participation, skewing the information ecosystem and narrowing democratic debate. In feminist terms, this is structural violence: the law and its enforcement are used to reproduce gender hierarchies.

International standards are clear. The right to free expression protects journalism; the right to marry protects intimate autonomy; and the prohibition of gender‑based violence requires states to prevent, investigate, and punish such abuse. Feminist legal analysis insists that the forms of harm described here — sexualised threats, forced exposure, reputational shaming, and the policing of family life — are not collateral to prosecution but themselves violations. Azerbaijan’s international commitments demand not only fair trials but also accountability for gender‑based abuses committed within the justice system.

The arrests of these nine women journalists do more than shrink the media landscape; they redraw the boundaries of who is allowed to speak. If women who investigate public interest issues can be imprisoned, humiliated, and stripped of intimate autonomy, the cost will be borne by every woman and queer person whose story goes untold. Treating this as a feminist issue is not a matter of branding, it is an analytic and moral necessity to see how gender shapes repression and to insist that any solution centres those most harmed.