On the anniversary of the deportation of the Chechen and Ingush people, a Russian ‘victory train’ is visiting the two republics — a grotesque parody of the trains that took so many to exile and death.

Today is the 78th anniversary of the deportation of the Vainakhs — the Chechen and Ingush people — to Siberia and Central Asia. Seventy-eight years since the entire population of Chechnya and Ingushetia were taken from their homes at gunpoint, in the dead of winter, and packed into cattle cars pulled by train.

But on this sombre date, a different kind of train has arrived to Ingushetia and Chechnya.

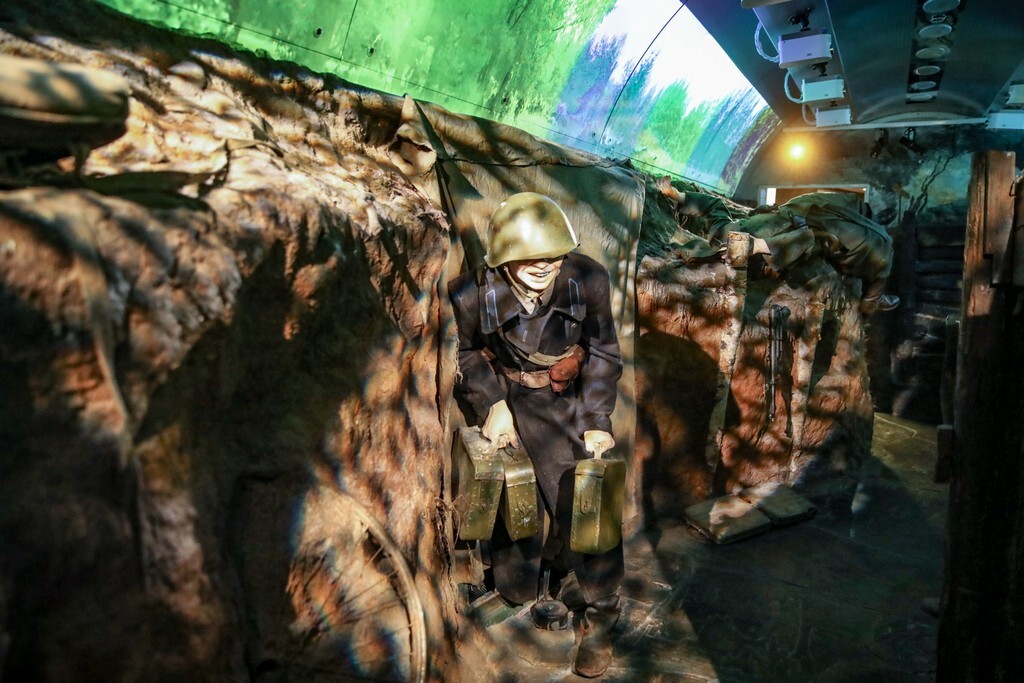

The ‘Victory Train’, a museum on wheels, is a Russian propaganda project within the framework of the creation in Russia of a new religion — the Victory Cult of 1945.

The Russian authorities created this train, stylised to look like it is from the WWII era, from various thematic carriages: a military hospital, refugees, soldiers, a coach of Soviet prisoners, and a car showing the torture of Soviet partisans and prisoners.

This idol of war has been travelling all over Russia for a year now, and schoolchildren, students, and civil servants are made to visit it on mandatory excursions.

As recent events show, the population is not only being educated through this and other projects of the victory cult, but is also prepared for future wars for a new USSR.

People are being accustomed to the idea of making sacrifices for the sake of the Kremlin, so that later, it may be possible to launch the Victory Train all over Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic countries, Romania, Hungary, and beyond.

But not far from the station in Nazran, Ingushetia, where this train pulled in, there is a monument to another train. This one is not stylised, but it is real, one in which the Ingush and Chechens were brought from their homelands to a cold, desolate, and unforgiving fate.

Because there is no family among the Ingush and Chechens not affected by the deportations, when 99% of the population of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was deported, and then the remaining one percent finished off in the mountains or caught and deported to Siberia.

Enemies of the people

What was the reason for the deportation, you may ask? And the reason in the Soviet Union was always the same. The authorities named a person or a people an ‘enemy of the people’.

How can an entire people, even dozens of peoples, be ‘enemies of the people’? Very simply, because in the USSR there was no other people than the Soviet people; any other identification deemed insufficiently Soviet were evicted, in many cases to certain death, to the steppes, taiga and other cold and inhospitable places.

It was officially proclaimed that the Vainakhs were being evicted for collaborating with the Nazis. Throughout the existence of Soviet power in Chechnya and Ingushetia, there were people fighting the Communists, even revolts, but these had nothing to do with the Nazis,

The argument for the expulsion of a people, tens of thousands of whom were still fighting on the front against the Nazis while perhaps several dozen fought the Soviet authorities, is meaningless, if not simply deceitful and cynical. But the Soviet authorities never cared much about their image, or the explanation of their cannibalistic initiatives.

Years after the return of the Chechens and Ingush from exile, Soviet propaganda talked about reports from the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, in which they described battles with saboteurs in the mountains as if they were on the scale of the Battle for Stalingrad.

The situation is completely different in modern Putin’s Russia, which is attempting to erase even the twisted memory of the tragedy.

The deportation took place on the day of the Soviet Army and Navy on 23 February 1944, with people rounded up in town squares on the pretext of participating in a solemn meeting for this event. This holiday remains important in Russia, and the mourning events of the Chechens and Ingush, their speeches, and the memories of the survivors, do not fit into the picture of the greatness of the USSR which Putin and his regime has been trying to restore for 22 years.

Therefore, for the last 10 years, Chechen authorities have directly banned the remembrance of the deportations, even imprisoning those who would dare to defy this.

In Ingushetia, with the efforts of Moscow appointed former head Yunus-bek Yevkurov, the authorities tried to introduce 23 February as the day of the army and navy, ‘just like everywhere else’. Yevkurov explained that the deportations could be remembered in the kitchen, as in the USSR.

The death train

But instead of the Victory Train that rolled through Chechnya and Ingushetia this year, the authorities there should have approached the Kremlin with an initiative to launch a ‘Deportation Train’ to run across the country.

It would have train cars displaying how entire families died of typhus, hunger, and cold.

Where hungry and exhausted people pull the corpses of their dead family members out to bury them in the snow.

Where NKVD soldiers beat a mother with their rifle butts, to make her throw away her dead child’s body.

Where children begging for water reach out their hands through the bars of cattle car windows.

Where an NKVD officer pulls a little girl by the hair from her mother’s body, before kicking her corpse from the train, leaving it to roll down a trackside embankment.

Such a train could have consisted of hundreds of thematic cars.

And on the platform, they could build a small village of houses, dugouts, and cattle sheds, where whole families are buried. It would be nice to install a wall against which adults and children would have been shot, for trying to find food for their loved ones.

This is how our ‘Deportation Train’ would be, because just under half of those who were driven into the train cars on 23 February 1944 never returned from exile.

Almost every family has lost someone close to them, and no one knows where they are buried or if they are buried at all, perhaps being devoured by wild animals in the cold winter of 1944.

There is a Soviet-era slogan about the Second World War — ‘No one is forgotten and nothing is forgotten’. These words have a completely different meaning for us.

We remember the names of almost everyone and pass this pain and memory to our children and grandchildren, and they will pass it on to their own. Because to us, truly, no one is forgotten and nothing is forgotten.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.