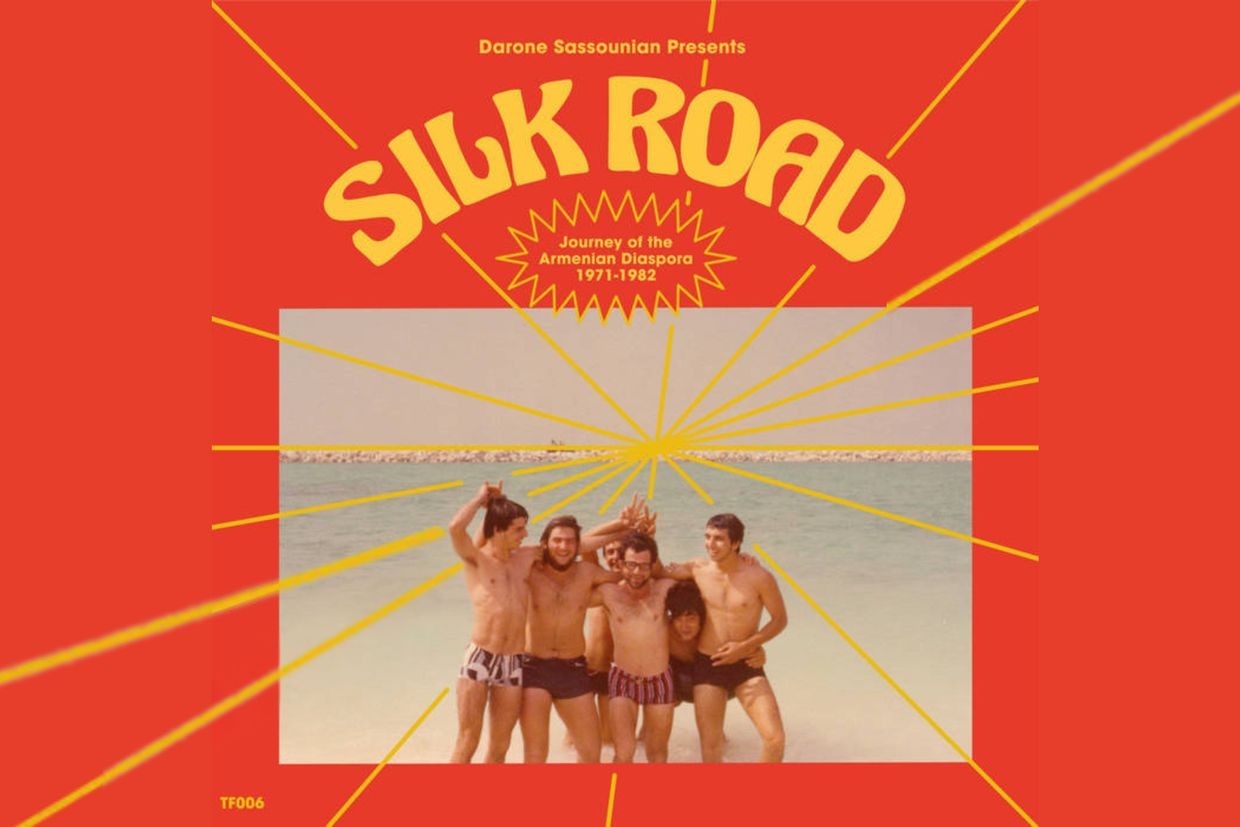

Review | Silk Road: Journey of the Armenian Diaspora (1971–1982) — a showcase of Armenian disco

★★★★☆

An exuberant and historically rich compilation of rare disco tunes, Silk Road offers a taste of the Armenian diaspora scene in 1970s Los Angeles.

Silk Road: Journey of the Armenian Diaspora (1971-1982) is a compilation album released via Terrestrial Funk records in 2021. The seven boogie/soul/funk/psych tracks featured on the album were assembled by Darone Sassounian, an Armenian–American DJ and producer from Los Angeles. Sassounian spent three years crate-digging all over the US, the Middle East, and Europe to bring us this project, a ‘token of appreciation and gratitude’ towards his ethnic background, and a dedication to the victims of the Armenian Genocide. As well as being a really funky record, Silk Road is an artefact, a musical synopsis of the history of the 20th century Armenian diaspora and a testament to its resilience.

Silk Road opens out like a flower. You can trace each track to a different Armenian community — Iranian, Turkish, Lebanese, French, Australian — but the bona fide headquarters of its sound is a small passport photo shop at the intersection of Santa Monica Boulevard and Edgemont Street, in what is now known as Little Armenia, Los Angeles. This was where Kevork Parseghian set up his business when he moved from Beirut to LA in 1966 with his family, wary of the chaotic politics of 1960s Lebanon.

They joined a growing Armenian population, which swelled dramatically through the 1970s and 80s once the civil war in Lebanon began in earnest, and then again as a result of the Iranian Revolution and the dissolution of the USSR. The majority of new Armenian arrivals settled in Los Angeles County, in cities like East Hollywood, Glendale, Pasadena, and Montebello.

After centuries of civil unrest and persecution, two world wars, and two genocides, to Armenian arrivals, LA represented — according to Armenian diaspora filmmaker Eric Nazarian — ‘a place where nobody cares who your father is’.

‘Here you can actually sigh,’ ‘sit down and sigh and say, “This is as far as we’re ever going to have to go” ’, Nazarian told Los Angeles Magazine in 2015.

The Armenian neighbourhoods in LA blossomed, opening restaurants, community centres, schools, starting newspapers, and preserving their Christian faith in new churches. Today, there are nearly half a million Armenians living in Los Angeles.

According to the same Los Angeles Magazine article, Parseghian Records was founded because freshly-arrived Armenians had been coming into Kevork’s shop and asking him to make duplicates of cassette tapes that had been originally recorded in Soviet Armenia. Eluding the Communist government’s restrictions on recording, people had contrived to tape songs belonging to the Armenian ‘Rabiz’ genre: love or heartbreak songs, set to synth dance beats but with Armenian folk elements.

Parseghian purchased equipment that tripled the amount of duplicates he could make at a time, and when customers came in with cassettes, he’d call up his sons, who’d skateboard to and from their family apartment to make copies, one of which Parseghian would keep for himself.

Parseghian soon understood what he had in his hands. He rented a space and made his first recordings with Paul Baghdadlian and Harout Pamboujkian (his is the sixth track on Silk Road) who were quickly dubbed ‘The Kings of Armenian Pop’. Parseghian Records grew and grew, and musicians from Armenia and all over the diaspora began arriving at his shop to record their music. It became the biggest purveyor of Armenian music in the world, continuing all the while to operate as a passport photo shop and notary public.

Sassounian’s research was largely centered on Parseghian Records, because it was a kind of sacred place for Armenian pop stars of the period, and also because it was Parseghian who helped many of them secure record deals. Indeed, Sassounian has called Parseghian Records ‘the sound of Los Angeles’s Armenian-American community.’

While Parseghian Records put out a lot of Rabiz music, what Sassounian wanted to showcase on Silk Road was Armenian disco. If other cultures had disco music, he thought, then surely Armenians did too.

The track that catalysed the project was ‘Sev Sev Achair (Black Black Eyes)’, by Jozeph Sefian, which Sassounian discovered in his dad’s record collection. ‘Sev Sev Achair’ is an Armenian folk tune, which Sefian transformed into a disco track. So began the hunt.

Silk Road is wonderful because it represents a unique example of the fusion of East and West — the disco structure fleshed out with flourishes of Armenian folk and Estradayin, the Armenian equivalent to French Chanson.

The album opens with a track by Marten Yorgantz, ‘Ammenïan Serdov (De Tout Coeur)’. Yorgantz moved from Istanbul to France, where he became the leading Armenian star after Charles Aznavour. He opened several restaurants in Paris and provided the nightly entertainment alongside a pianist and guitarist. ‘Ammenïan Serdov’ is a personal favourite off Silk Road; it’s something about the vibraphone synth and the gusto with which Yorgantz says ‘YES!’ before each chorus.

‘Tears on my Eyes’ by Avo Haroutounian, the fourth track, is another favourite. This is the only song ever recorded that features Haroutounian’s voice; he considered himself a terrible singer, and only taped this track because he was recovering from heartbreak and wanted to cheer himself up, according to Sassounian, by making a disco-funk love ballad. Haroutounian’s untrained, vaguely yelpy voice is incredibly charming. Sassounian calls it ‘one of the holy grail Armenian records’ — only 1,000 were ever pressed, and Sassounian has seen just three of them.

After his first and only record, Haroutounian abandoned his solo career to collaborate with Harout Pamboukjian, for whom he produced, assisted with songwriting, and played bass. Haroutounian and Pamboukjian were childhood friends in Yerevan, and bumped into one another outside Parseghian Records. Their ensuing collaboration proved incredibly fruitful — Pamboukjian’s is the sixth track on Silk Road. ‘Taparoum Enk (We’re Wandering)’, like his first album Our Eyir Astvats (Where Were You God?), focuses on themes related to the Armenian Genocide and the diaspora experience.

For all its cheer, the subtext of the Armenian diaspora’s collective suffering renders Silk Road very moving. The biographies of every featured artist are marked by persecution, war, or displacement, and yet the album’s sound is one of celebration — almost as if the exuberant syncopated basslines, synthesisers, and electric rhythm guitars of disco (itself partially the product of other American immigrant communities) were adopted by Armenians as the language of a kind of relief, whereby America seemed a place of hope. This makes Silk Road much more than just the perfect record to dance, shower, cook, or roller skate too — and if Sassounian hadn’t found that one record in his dad’s collection and set about the project, this elusive genre may have been lost to history. We can only wish it were longer.

Album details: Silk Road: Journey of the Armenian Diaspora (1971 - 1982), various artists collated by Darone Sassounian, 2021.

🗞️ Subscribe to OC Culture Dispatch

For our culturally curious readers: a free, biweekly selection of film, book, and music recommendations from the Caucasus. Our team offers a varied selection of hidden gems, cherished classics, and notable new releases from all over the region, included in our newsletter.

Subscribe here