This year marks 20 years since Georgia’s Rose Revolution, and five since the Velvet Revolution in Armenia. Both were born of a desire to end corruption and build a democratic future; their successes and failures, though, have remained a matter for debate.

‘Come out all of you who think that the building and development of the modern Georgian state started this day’. This was the call of the organisers of gatherings in Tbilisi and Batumi last November to commemorate the anniversary of the 2003 Rose Revolution.

Mikheil Saakashvili, then leader of the opposition, and his allies stormed Georgia’s Parliament on 22 November 2003, preventing President Eduard Shevardnadze from properly launching the new parliament. It was the culmination of widespread protests over the results of parliamentary elections in which Saakashvili’s United National Movement party (UNM) and the Burjanadze-Democrats, another opposition coalition, claimed election fraud.

A day later, Shevardnadze resigned, sweeping the Saakashvili-led coalition to power.

The event was internationally hailed as a ‘peaceful revolution’ through protests that largely adhered to the principle of non-violence.

Armenia’s 2018 Velvet Revolution occurred only five years ago, 15 years after the Georgian Rose Revolution, marking yet another major milestone in peaceful transfer of power in the region.

In 2018, mass demonstrations and a campaign of civil disobedience engulfed Yerevan after President Serzh Sargsyan became prime minister, effectively granting himself a third term, after revising the constitution.

Even though Sargsyan’s amending of the constitution was the trigger for the protests, a whole range of grievances brought people into the streets, including corruption, unfair elections, nepotism, police reform, and human rights abuses.

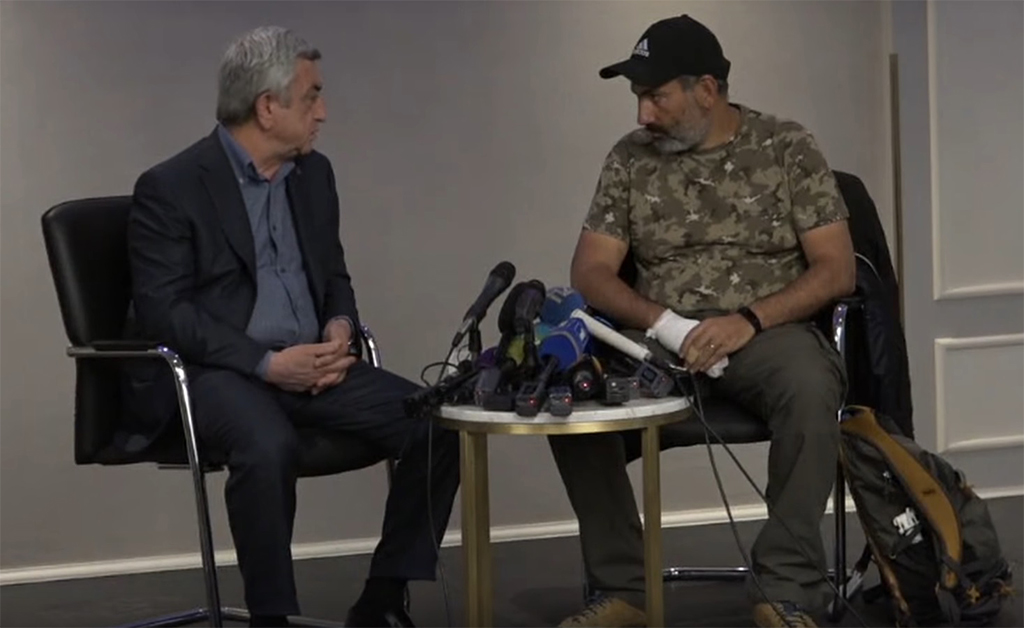

As in Georgia, the Armenian protests had a clear figurehead, longtime opposition politician and journalist Nikol Pashinyan. His meeting with President Sargsyan in Yerevan’s Marriott Hotel, which lasted mere minutes before Sargsyan stormed out, saw Pashinyan rise from a backbench politician to an icon of the protesters.

On 23 April 2018, Sargsyan resigned as prime minister, noting in his resignation statement that ‘Pashinyan was right.’

The prospect of endless rule by Sargsyan and his political allies was considered too much of a humiliation for the Armenian public, argues analyst Eric Hacopian. The 2018 revolution, says analyst Nerses Kopaylan, was a ‘collective response to years of corruption, underdevelopment and wealth disparity’.

Disillusionment

Last year’s 23 November rallies to mark the Rose Revolution anniversary in Georgia were not purely commemorative, and the organisers chose their name (the Public Committee for Mikheil Saakashvili’s Freedom) for a reason: the Rose Revolution’s renowned leader is expected to meet its 20th anniversary this year in prison on charges of abuse of power.

In a post-revolutionary excitement, especially during 2004–2006, not everyone was ready to lend an ear to democracy watchdogs in Georgia, but several years later, the rights group the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA) brought a police murder case to the national spotlight — the infamous case of Sandro Girgvliani’s murder. This convinced many Georgians that despite impressive structural reforms, police impunity and the judiciary’s obedience to the government were still here to stay.

But for some in Georgia, Saakashvili’s rule was anything but democracy to begin with.

For Nukri Shoshiashvili, a conservative commentator at pro-government Georgian TV channel POSTV, the revolutionary government under Saakashvili and the UNM replaced previously dysfunctional state institutions with efficient bureaucracy, ‘but a thrust towards democratic development was entirely put on hold’.

‘In terms of freedoms and social equality, it brought regress. The country deviated from democratic development, and its sovereignty has been curtailed’.

In terms of comparison between the old and post-revolutionary governments, this may not be a widely shared view on the Rose Revolution in Georgia. But the new government under Saakashvili did frustrate many, including some of the leading figures of the revolution.

Davit Zurabishvili, who was a civil and political rights advocate before joining the revolutionary coalition as an MP, fell out with Saakashvili’s team soon after coming to power. He says that leading members close to Saakashvili — ‘three–four individuals calling the shots’ — were open with him about preferring ‘authoritarianism over democracy’.

‘They had Pinochet as a role model. They had this sort of naive notion that some sort of “enlightened authoritarianism” would be a precursor to democracy.’

This turned out to be a bad element mixed with what Zurabishvili described as the government’s inability to compromise or admit mistakes.

‘Backing down was like death for them’, Zurabishvili recalls.

According to Tina Khidasheli, who chaired GYLA in 2002–2004, the key problem Saakashvili’s government had was the ‘entirely dehumanised’ state they had built.

‘The failure to ensure an independent judiciary, problems the media faced, cracking down on rallygoers, harassment and unlawful firings of people who disagreed, imprisonments — all these later served as instruments for this dehumanised system that Saakashvili created’.

Despite major differences, fears have been raised that Pashinyan’s government may be falling for some of the same mistakes as Georgia’s revolutionary government.

In 2018, an aura of hope and excitement gripped the country as people cried out for a democratic, prosperous and free Armenia.

However, government inexperience, incompetence, and in particular, a disastrous military defeat against Azerbaijan in 2020, as well as the imminent threat of the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenians, have left many feeling traumatised and disillusioned.

Under the new government, 2018 and 2021 parliamentary elections in Armenia were given stamps of approval by international organisations such as the OSCE. Since the revolution, Armenia has moved from ‘authoritarian’ to ‘hybrid’ regime in The Economist’s annual Democracy Index, overtaking the previous ‘beacon of democracy’ in the region — Georgia.

But recent stories such as the violent arrest of the parents of fallen soldiers of the 2020 war who were protesting a visit by Pashinyan to Yerevan’s military pantheon, or Parliamentary Speaker Alen Simonyan spitting in the face of a member of the general public after being called a ‘traitor,’ have again raised concerns amongst civil society groups.

In Armenia, corruption was a major concern for protesters in 2018. Between 2018 and 2021, Armenia rose 26 places in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which analyses the perceived state of corruption amongst the nations of the world. In 2022, however, Armenia fell in the rankings, dropping three places.

According to Isabella Sargsyan, the Program Director of Eurasia Partnership Foundation, a leading civil society organisation in Armenia, the level of corruption, especially petty corruption, indeed went down after 2018. However, Sargsyan also stated that issues of corruption still exist, and that interestingly, the forms of corruption which exist in Armenia are evolving.

‘The ruling party is already engaged in making favours for some businesspeople, there are issues of nepotism, conflicts of interest’, Sargsyan said.

Sona Ayvazyan, director of Transparency International Armenia says that ‘studies indicate that systemic, institutional corruption has declined in Armenia’.

‘However, the typology changed — pushing forward nepotism as the major problem instead of bribery, which was dominant in the past.’

Ayvazyan moreover notes that the types of corruption which exist in Armenia are evolving.

‘There are fresh schemes of corruption, such as contributions by businesses to municipalities with anticipation of construction permits, or discounted prices of real estate and interest-free loans by the banks to high-ranking officials. Such practices obviously raise serious concerns and undermine the government’s fight against corruption.’

In Georgia too, where the elimination of corruption was seen as one of Saakashvili’s crowning achievements, problems remain.

In April, the US government imposed sanctions on several leading judges that watchdogs had described as being leaders of a ‘clan’ in Georgia’s judiciary. The announcement confirmed fears that Georgia continues to struggle with high-level corruption and a lack of checks and balances while mostly maintaining the Rose Revolution legacy in eradicating petty corruption.

In the shadow of war

For the former Tbilisi mayor and Saakashvili ally Zurab Tchiaberashvili, human rights violations were an important factor in the downfall of the UNM rule. He says this was also the most discussed topic publicly.

Still, Tchiaberashvili underlined that far more fundamental reasons for public discontent originated from the economic transformation of the entirety of Georgian society, including mass credit withdrawals and inflation in later years.

But Tchiaberashvili believes that the most important factor that worked against the post-Revolutionary government was the ‘fear of Russia’.

‘Saakashvili’s government was perceived as a troublemaker. This was most fundamental and still present in our psyche’.

Indeed, conflict and geopolitical considerations marked a key challenge for both post-revolution governments.

Georgia saw a war erupt with Russia only five years after the Rose Revolution.

Only two years after the Velvet Revolution, Azerbaijani forces crossed the line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh, igniting the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020.

Azerbaijani military victories, large land handovers by the Armenian side and the violent post-war incursions led to a rise in disillusionment with the post-revolution Pashinyan government.

‘I don’t think we can link the wars to the revolutions directly, but the personalities of both leaders was a contributory factor’, says analyst Thomas de Waal.

‘Both leaders were disruptors and their disruption of the status quo helped create a security vacuum that was filled by conflict.’

‘In retrospect, Saakashvili made a mistake in looking so much to the United States and believing that Georgia was a bigger priority in Washington than it really was. That emboldened him to be much more confrontational with Russia than was wise, while libertarian US-inspired economic policies were no cure for the deep-seated socio-economic problems much of the Georgian population was enduring’.

In the case of Nikol Pashinyan, according to de Waal, ‘his lack of international experience and poor diplomatic instincts meant that he first over-encouraged President Ilham Aliyev with the idea of a more dynamic peace process and then deeply disappointed him’.

‘These mixed signals, which you would not have seen from his predecessors, were one factor (but not the only one obviously) in Aliyev’s frustration and subsequent decision to go to war in 2020’.

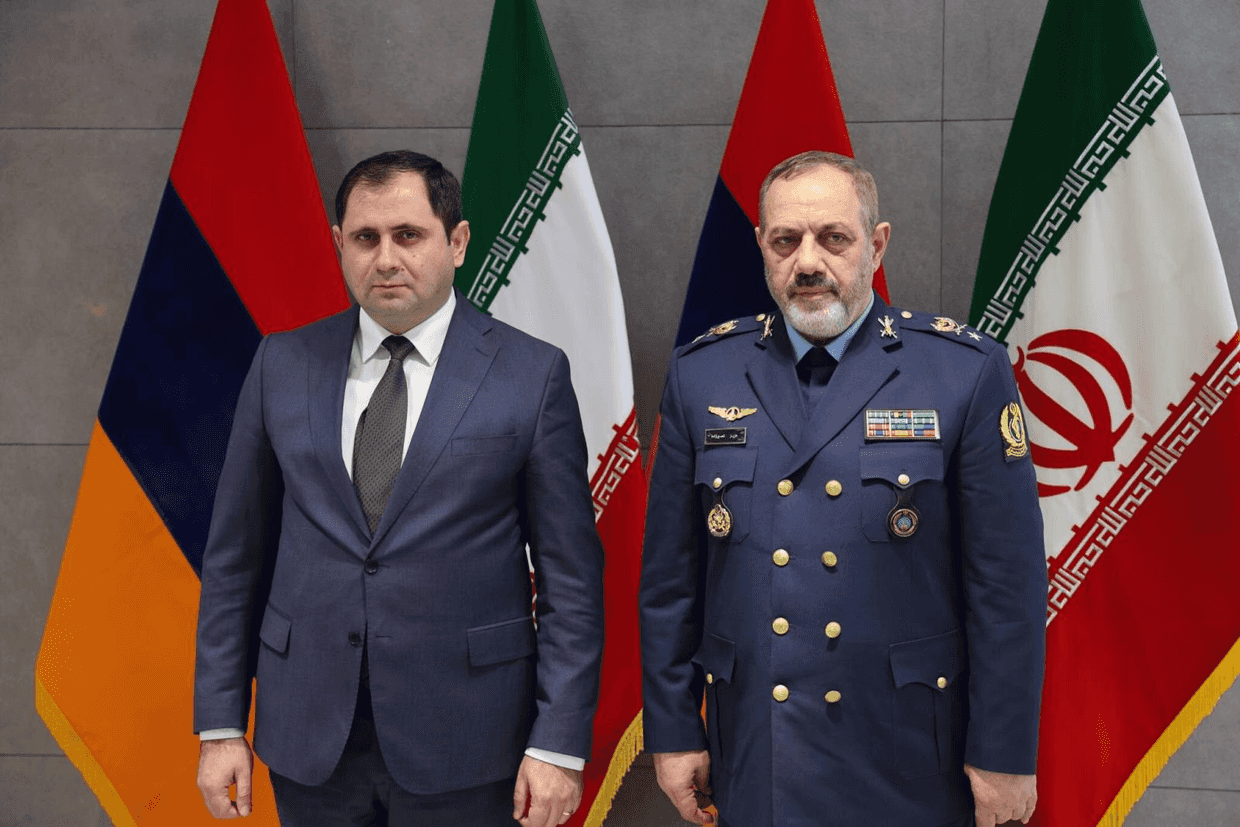

Armen Ashotyan, a former Education Minister under Serzh Sargsyan, says that there was a direct connection between the revolution and the war. According to him, the Pashinyan government failed to reform the army and failed in the diplomatic sphere.

Lena Nazaryan, a member of parliament for the ruling Civil Contract party and close ally of the prime minister, pinned blame on the 2020 defeat on the former regime, arguing that Azerbaijan had already been preparing for a large-scale invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh. She argues that the 2016 April war, before the revolution, was evidence of Azerbaijan’s intentions, preceding factors that came out about after the revolution.

Analyst Eric Hacopian argues that the Pashinyan government had to deal with an overstretched army, riddled with corrupt practices. However, Hacopian also notes that the post-revolution government failed to adequately reform the army and to adequately argue Armenia’s case to international actors and audiences.

The post-revolution atmosphere did not contribute to the solution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Initially, hopes were stirred after what were described as ‘productive talks’ between Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev.

But in the end, the new Armenian government failed to anticipate the war and had issues with decision-making and diplomacy in the lead-up to the war, which was exacerbated by bravado from the prime minister, who adopted nationalistic rhetoric when it came to Nagorno-Karabakh, famously saying during a speech that, ‘Artsakh is Armenia, period’.

A contested legacy

Both revolutions still have contested legacies both at home and abroad, but often for different reasons.

Analyst Thomas de Waal says that ‘apart from the main issue that Armenia and Georgia are very different countries, the main difference came after the revolutions.’

‘Mikheil Saakashvili was probably a more skilful politician than Nikol Pashinyan in mobilising support for his rule, especially in his first term as president, both abroad and at home. Saakashvili smashed organised crime in Georgia effectively and cracked down on everyday corruption — his most lasting achievements. Pashinyan has been less effective in government’.

In Georgia, political figures and historical events rather than political ideas divide Georgians the most, and the former president appears to be one of these controversial dividing figures.

Yet still, some Georgians, even some of Saakashvili’s adversaries, still cherish the legacy of the 2003 Rose Revolution.

‘Of course! It was time for the government to change’, says Koba Amirkhanashvili, the former deputy leader of Shevardnadze’s former party, the Citizens’ Union.

Amirkhanashvili, a heavyweight in Shevardnadze’s party, marched together with others to Parliament on 23 November. Known for wearing military fatigues in Parliament, he ended up with a flower in his hand that later became the symbol of the first peaceful change of government in post-Soviet space.

‘Saakashvili just put it in my hand’, Amirkhanashvili remembers.

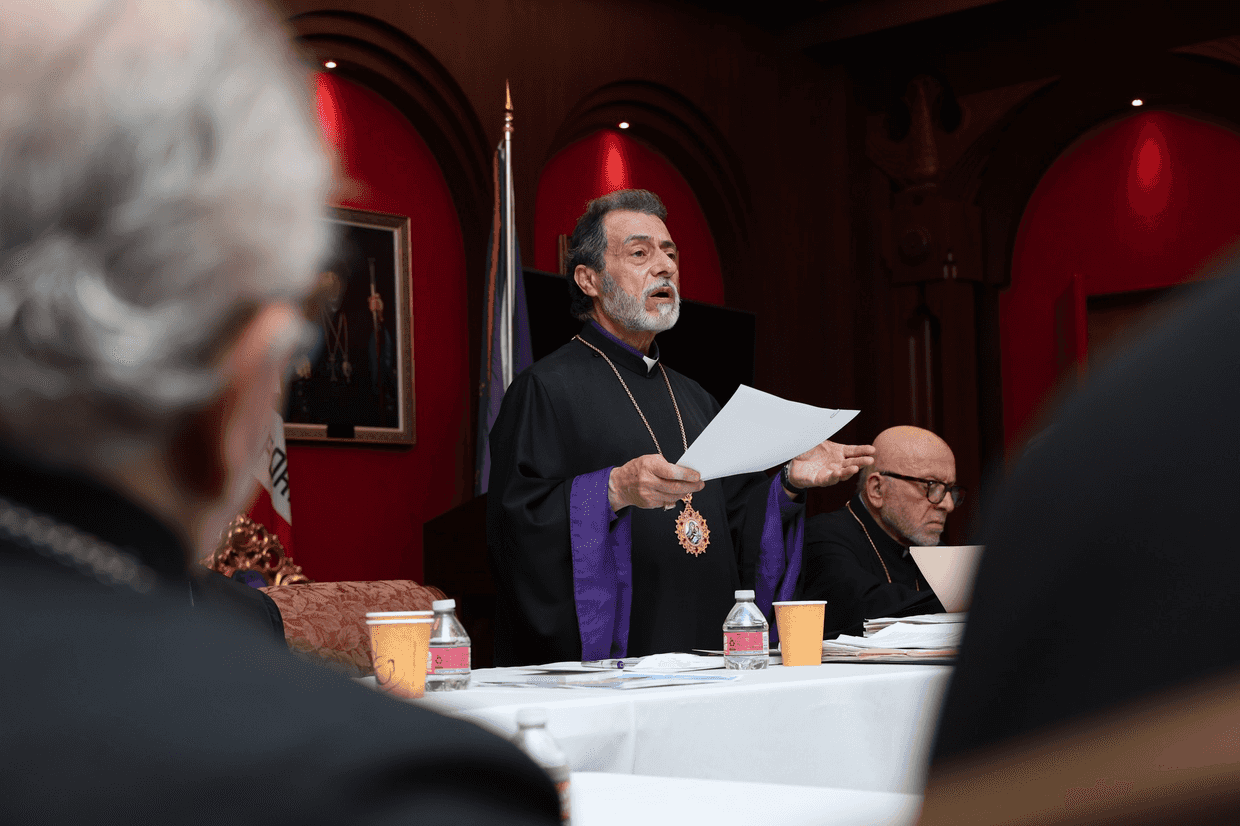

The 2018 Armenian Revolution’s legacy is still very much under debate, particularly as the conflict with Azerbaijan rages on, and the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenians remains an imminent threat.

However, the revolution was undoubtedly a display of people power in Armenia, and transformed the country from a despotic clan-based political system into a democratic one, where elections are free and fair.

This article was a joint production between CivilNet and OC Media.