The concept of industrial monotowns popular in the Soviet Union proved ineffective in the context of the market economy. Many city-forming enterprises have become completely uncompetitive — but cities continue to live.

‘The plant was powerful! And this power was visible, at least throughout Georgia. Everyone would envy Rustavi!’ — says Givi Zurashvili, a resident of Rustavi who worked at a metallurgical plant for 40 years.

‘I entered the factory right after school — in 1970’, he says, adding that he also later received a higher education in Moscow. After studying, he returned to ‘the same workshop’, then moved to the HR department, and eventually became deputy director for personnel.

‘I left in 2010 when there was already nothing to do there’.

The history of Givi’s family, like many other residents of Rustavi, is intertwined with the history of the construction and establishment of a metallurgical plant. It begins with a large-scale mobilisation: 5,000 young people born in 1926 were selected from all over Georgia to be sent to the metallurgical centres of Ukraine and Russia to obtain qualifications.

Givi’s father was among the 5,000 sent.

‘He studied in Yenakiyeve, in the Donetsk region, there is a metallurgical plant there. He got acquainted with my mother there and took her with him — she was 16, he was 19. When they returned in 1947, the first workshops were already running’, Givi says.

Many of those who were involved in the construction of the plant continue to live in Rustavi.

In addition to the young professionals returning to Georgia, qualified specialists from Ukraine and Russia also came to work and start up workshops.

‘Many of these people have left over the years, and those who have adapted to the local conditions have remained’, Givi says.

As a result, a plant covering the complete metallurgical cycle was built: from coke chemistry to pipe production.

According to Givi, around 15,000 people worked at the plant initially. ‘In the 1960s, many processes were modernised and automated, at the end — at some point by the 1990s — over 12,000 people worked at the plant’.

According to him, at the end of the 1980s, the plant produced 1.5 million tonnes of steel, 550,000 tonnes of pipes, 900,000 tonnes of sinter, 650,000 tonnes of pig iron, and 600,000 tonnes of coke a year.

The large construction site and then the giant factory, which accumulated specialists from different cities and republics, made the city of Rustavi international. ‘We lived together!’ says Givi.

Single-industry city

Rustavi is located 25 kilometres south-east of Tbilisi. This city and the metallurgical plant was erected in a short time, on the site of an ancient fortress that existed in place of the city before the Middle Ages.

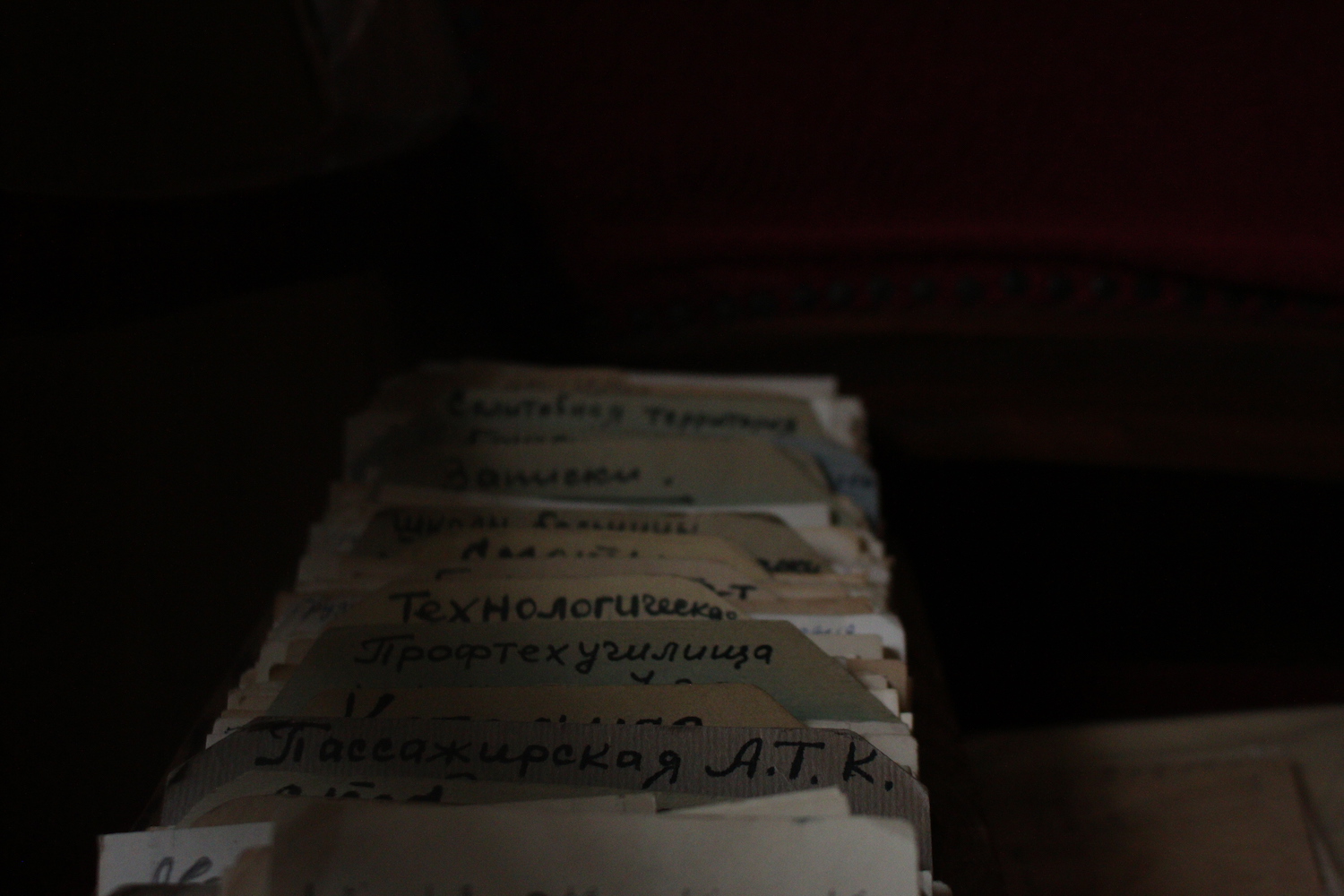

The coexistence of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ is the main plot of life in Rustavi. It organises the urban space, the stories of local residents, and the exposition of the Museum of the History of Rustavi. The museum’s first floor contains an archaeological exhibition of antiquities found during excavations. The second, Soviet, floor contains exposition about the history of the construction of the giant metallurgical plant.

‘The ancient city was just on this territory. Everything that you see here was literally pulled out by archaeologists from under the excavator bucket’, says a museum employee.

‘When they began to build the factory, they began to find the remains of ancient settlements. Archaeologists initiated excavations, but it was very difficult — it was not possible to work calmly. There was an urgent need to build a factory and a city at the same time.’

In the Soviet Union, single-industry cities and towns that appeared in their hundreds around town-forming enterprises reflected the essence of total industrialisation and served the development of vast spaces.

For many residents of Rustavi, the history of the city is inextricably linked with the history of the plant — with its bright past, when they were building together, working together, creating families, regardless of their origin, status or position at the factory. But through the nostalgic voices of the inhabitants of Rustavi, Soviet history painfully resonates with the socio-political processes in post-socialist Georgia.

‘Heavy industry all over Georgia is gone!’

‘Heavy industry all over Georgia is long gone. Those enterprises that existed were sold into private hands, often to foreign owners’, says Zoia Maisashvili.

She has been associated with the Rustavi plant for nearly thirty years. In recent years, she has been the director of the State Institute of Design of Metallurgical Plants. There is a whole collection of photos of the plant on the walls of her office. She tells about many cheerfully and defiantly, remembering how it was before, but when she talks about the current state of affairs at the plant, her voice noticeably lowers.

Since 2006, Zoia has not worked in the factory, but she is in the know about the latest information.

‘They are going to completely stop the plant. Now there are about 900 workers there. Plus, those who are in the administration, so there are a total of twelve hundred or a few more people’, says Zoia.

Zoia began working at the factory immediately after leaving school, attending evening classes at Tbilisi University at the same time. After being employed as a worker, over time, she became a member of the party and trade union organisation.

‘I was born in Rustavi and never wanted to go anywhere from here. When I would leave for a short while, I remember that every time when I would enter the city on my return I would feel a warmth right away — a feeling of being home’, she says.

In 1999–2005, with the direct support of their trade union, the Rustavi metallurgists protested the government’s decision to sell the plant.

‘For six years we fought because we understood that such objects, which are everything for the city — the main arteries — cannot just be sold at auction!’

Despite the protests, in October 2005, the plant was sold for $21 million — which according to Zoia was 25 times less than the value of the enterprise including all of its infrastructure.

‘The next day I wrote a statement and left. I just couldn’t stay with those I had fought against’, says Zoia.

‘I don’t want my country to rely only on income from tourism — that my people would have only a service function’.

De-industrialisation of Georgia

As in many other countries of the socialist bloc, the collapse of the Soviet Union led to mass de-industrialisation in Georgia. During the 1990s and 2000s, dozens of large heavy industry factories were either completely ruined and closed or lost most of their resources — in particular, because their equipment was sold as scrap metal.

Many experts in Georgia’s political economy point to the neoliberal reforms that followed the country’s independence as the causes of the problematic situation in the industrial sector. In their view, the privatisation of state assets, deregulation, the opening of domestic markets to foreign capital, and the flexible internal labour market have significantly affected industry.

According to data cited by Tato Khundadze, a political-economic expert and lecturer at the Georgian American University, in 1987, around 643,000 people were involved in industrial production in the country, while in 2015, the industrial sector employed only 116,000.

According to official data, Georgia’s unemployment rate in 2018 was 12.7%, almost 250,000 people. However, experts are dispute such figures, since, according to the law, all landowners are de jure considered to be employed, while de facto they often don’t have the resources to work the land or receive profit from it. Landowners make up about half of Georgia’s working-age population.

After the collapse of the USSR, deregulation of labour rights took place in Georgia, and the share of employment in industry was significantly reduced. Over the past 10 years, a whole series of working strikes and protests have taken place in the country, both in industry and in the services sector. Most of the protests are caused by poor working conditions, violations of labour rights, and low wages,— analysts attribute this situation to the negligence of private companies in relation to their employees.

The urban geography of small and dispersed industrial cities turned out to be ineffective in the context of a market economy, where many city-forming enterprises have become completely uncompetitive. Rustavi repeated the fate of many former single-industry cities and towns. Once a giant factory that provides jobs from 11,000–12,000 people, for the last 25 years it has been in a very unfavourable position.

Anthropologist Jeremy Morris believes that single-industry towns, such as Rustavi, should be considered both from the perspective of the value potential for the economic development of the country and from the perspective of the development of the post-socialist ‘heritage’ of urban space by the people themselves.

[See also OC Media’s photo story: Rustavi: The city of factories]

This article was produced in partnership with Open Democracy Russia. A similar version is available on their website.

This article was produced in partnership with Open Democracy Russia. A similar version is available on their website.