The Tsova-Tush children’s book aiming to save one of Georgia’s most endangered languages

A 2019 documentary failed to find anyone under the age of 30 who knew Tsova–Tush.

Former actor Revaz Orbetishvili’s first language is Tsova-Tush, yet he has never performed in a play in his native tongue. Only about 300 people speak the northeastern Caucasian language anymore — down from a reported peak of 3,000 or so in the 1980s.

‘The language needs to be saved’, he says.

Orbetishvili, who has worked for regional cultural centres since 1987, has also never watched a feature film or read a novel in Tsova-Tush. Such things do not exist. As a result, when Jesse Wichers Schreur, a Dutch linguist who has been working on the language since 2017, mentioned that he’d like to use his network to raise money for a project to give back to the community that had hosted him while he studied their language, Orbetishvili knew exactly what he wanted to fund: a children’s book, to introduce new generations to their ancestral tongue.

Tsova-Tush, also sometimes called Bats or just Tush, is unique on several fronts. It’s the smallest minority language in Georgia, only spoken in the village of Zemo Alvani, in the eastern region of Kakheti. The ancestors of the modern Tsova-Tush community relocated there from the mountains of Tusheti following some sort of natural disaster — a landslide, avalanche, or flood — in 1830.

Unlike other minority language groups, Wichers Schreur says, the Tsova-Tush considered themselves ethnically Georgian before their language was first officially described in 1846, an identification likely developed while they still lived isolated in the mountains of Tusheti.

Also unusual: that recorder of the language, a priest named Iob Tsiskarishvili, was a native speaker of Tsova-Tush (written grammatical sketches of this sort were normally done by foreign academics, not members of the language community themselves). Tsiskarishvili is the first person known to have written anything at all in Tsova-Tush, which has largely been a spoken language.

Even in the 1800s, when the whole community still used the language, there were concerns about its future. The worries were different though:

‘The focus was more on bilingualism, the language contact, what at the time they called the “bastardisation” of the language’, Wichers Scheur, whose doctorate focused on the topic, says.

‘Everyone of the community spoke the language at that point, but the Georgian influence was seen as a deterioration of the language, as in many places in the world. Once you can point to a foreign influence of the language, that’s usually seen as a negative’.

Those influences are highly visible today — there are thousands of Georgian loan words, and even Georgian grammatical structures used, with Tsova-Tush vocabulary swapped in.

Because speakers of Tsova-Tush were bilingual and considered ethnic Georgians long before the Soviet period, they did not suffer from the same level of discrimination and oppression that impacted some of Georgia’s minority language communities. However, the language also did not receive the support that the languages of ethnic minorities received at various points — resources to create newspapers, radio broadcasts, and school textbooks, among many other things.

To this day, Tsova-Tush resources are limited. Beyond the oral repertoire of traditional songs and poems, there are some bilingual dictionaries, an academic collection of stories and poems, and a few documentaries (Orbetishvili seems to be in most of them). There is a not very widely distributed Georgian–Tsova-Tush version of the classic Georgian learning book Deda Ena, but no textbooks and nothing else for children to read.

For Orbetishvili, who was born in 1958, this wasn’t a problem — he learned Tsova-Tush at home as a child and only learned Georgian once he went to kindergarten. He taught his children too. However, recent generations speak less and less — a 2019 documentary set out to find anyone under the age of 30 who knew the language and failed. Wichers Schreur guesses that no one under 60 can fluently speak the language. Mixed marriages, Georgian-language schooling, and migration to the cities are bringing a process that had begun in the 1800s to a close.

Orbetishvili began to notice the decrease when he was finishing school in 1975.

‘That’s more or less when mixed families began to form, and the language also became mixed’, he says. ‘They marry non-Tush women, mothers don’t speak Tsova-Tush, and whether they like it or not, the children will speak Georgian. Then the neighbouring children too are forced to speak Georgian, and they forget [Tsova-Tush]’, he says.

Wichers Schreur adds that maybe nine times out of ten, in a mixed family with a Tsova-Tush speaking parent and another parent who speaks Georgian, Ossetian, Chechen, or what have you, the child will end up speaking Georgian because that’s the language the parents communicate in to each other.

‘Only a few people know this language’, Orbetishvili says of the present day. The natural passing down of the language through families isn’t strong enough anymore.

He adds, however, that television, internet, and social media have helped rather than hurt his cause, preserving songs and poems and allowing them to be easily shared. But to save the language, ‘We want them to learn it through books’.

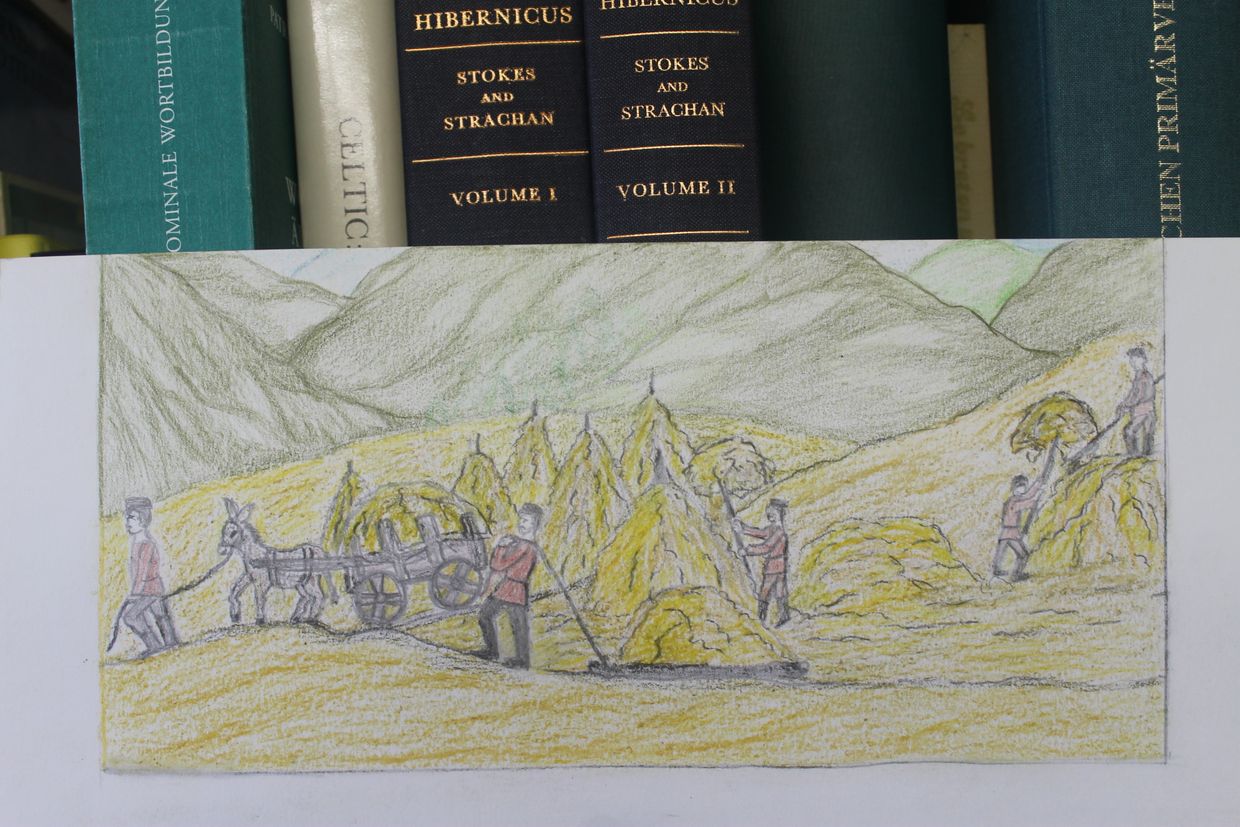

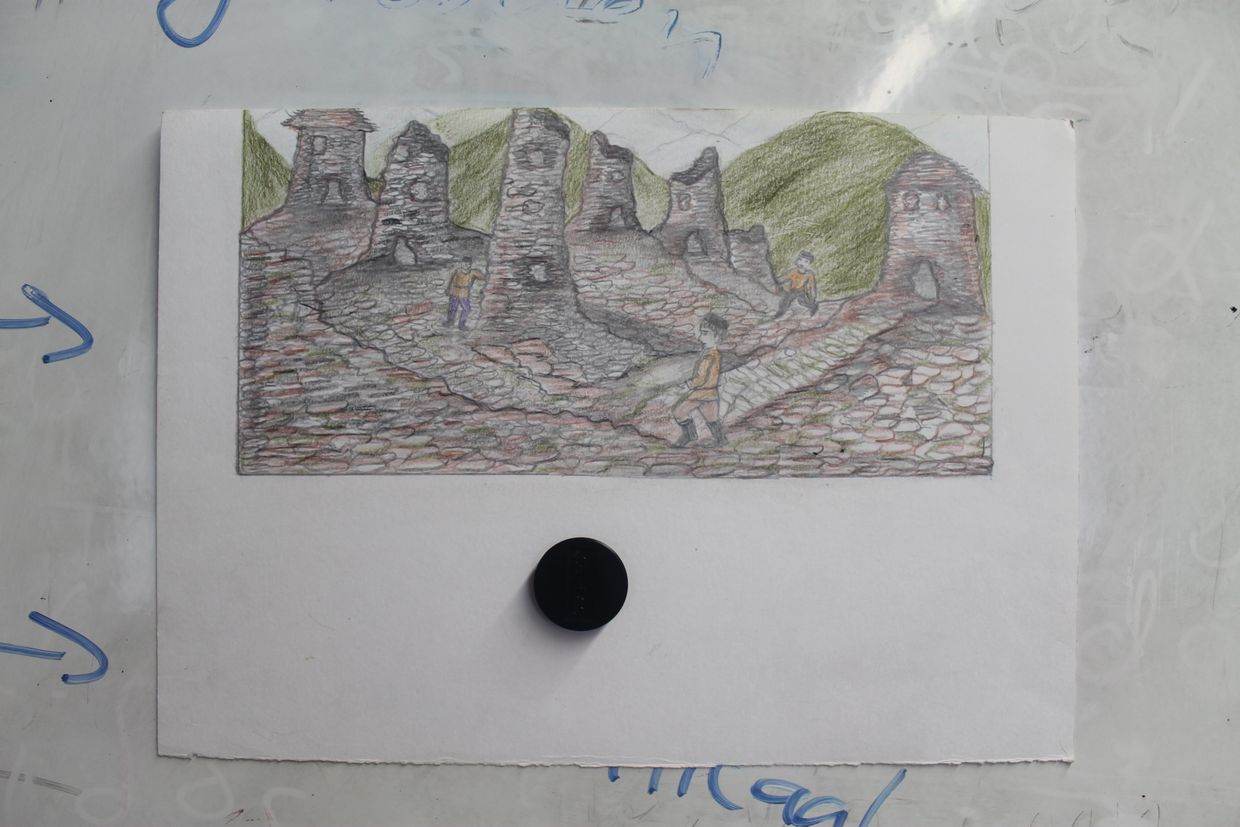

The next step was deciding what the content of the book would be. Orbetishvili reached out to local artist Natela Khetsoidze, giving her free rein to illustrate. She drew scenes from her childhood — summers in the mountains, herding sheep, learning traditional crafts, eating khinkali, and exploring the ancient towers where her forebears lived. The transport helicopter and tourists in their bright tents make appearances as well, capturing the broad strokes of Tushetian life in charming coloured pencil.

The story — presented in Georgian, Tsova-Tush, and English — is simple: children finish the school year and ride into the mountains for the summer. They frolick, the men go to the shrine, they shear sheep, and eventually they return home and go back to school. Tushetian cultural vocabulary is introduced: ‘chobanchai’, a hot drink extracted during cheesemaking, ‘alachoki’, a tent made from a large woolen cloak, ‘khidobani’, a children’s game in which one child runs through a tunnel made from the arms of the other children — one hits the runner on the back, if they guess who it was, they switch places.

Khetsoidze is a self-taught artist from Kvemo Alvani and grew up speaking Chagma-Tush, a dialect of Georgian, not Tsova-Tush. She moved to Zemo Alvani in 1999, when she married into a Tsova-Tush speaking family. Hers is a typical mixed-language family in that her children did not learn Tsova-Tush, but she is generally passionate about preserving the culture of the mountains and hopes the book will contribute.

‘I want children to quickly master and learn the Tsova-Tush language, and I also want to open various groups where children can learn the art of Tushetian handicrafts, which are currently inaccessible’, she says.

Aside from drawing, Khetsoidze also paints, weaves, and embroiders in Khevsurian and Tushetian styles.

After nearly two months of drawing in the breaks between her work as a cleaner at the village school, she was finished. Orbetishvili then wrote the descriptions, and the first Tsova-Tush children’s book was almost completed.

Orbetishvili and Wichers Schreur are now figuring out how to print it (no one involved has ever worked on the publishing end of a book before). They’re aiming for 400 copies — one for each of the 250 or so families in the village with young children, 100 for cultural institutions, and 50 spare for curious linguists and donors and so on. Since everyone involved refused payment for their work, they’re hoping the crowdfunded pot might even cover a second book, posters, or other classroom resources.

There are sometimes classes held in the village, but Wichers Schreur says they seem to start and stop as the children involved lose interest. He mentions as a possible model a Canadian programme that provides funding for elder speakers of endangered languages to take time off work and simply spend time with children in their communities while speaking their native language, but he isn’t sure who would support such a programme in Georgia.

Meanwhile, despite Orbetishvili’s general optimism for all things Tsova-Tush, the former thespian is unenthused about the idea of putting on a play in the language.

‘No one will understand it’, he says. ‘It doesn’t make sense’.

This article was translated into Russian and republished by our partner SOVA.