Will Abkhazia be able to avoid an energy collapse this winter?

Abkhazian authorities promise they won’t allow a collapse of the energy grid this winter. But can they deliver?

Every year during the autumn and winter period, Abkhazia faces an energy crisis, which negatively impacts both the economy and the daily lives of its residents, as they attempt to cope with rolling blackouts.

The current state of Abkhazia’s power grid is characterised by a high level of wear and tear and outdated network equipment. This, according to the Abkhazian Energy Ministry, leads to significant losses during electricity transmission, and in some cases, to low voltage in distribution networks. The ministry says that to avoid major accidents and power shortages in the future, the grid must undergo modernisation. But considering the budget is already tight, and the vast majority of Abkhazia’s energy needs are supplied by Russia and the Ingur HPP, which is shared by the Abkhazian and Georgian governments, it is unclear how they plan to do this.

According to the results of an audit conducted in May 2025, ₽12 billion ($150 million) is needed to replace outdated equipment and power lines, Abkhazian Energy Minister Batal Mushba said during a parliamentary session on 20 November.

Abkhazia consumes 4 million–4.5 million kWh of electricity per day. Considering the population is no more than 240,000 (according to a 2011 census), this is more than double the rate in Georgia. Much of this energy is used on cryptocurrency mining — often illegally — not for the needs of the average resident or the general well-being of society.

While there has been a slight decrease in total consumption in 2025 compared to 2024, the Energy Ministry itself acknowledged in November that the savings amounted to only around ₽200 million ($2.5 million) — or a quarter of the projected total expected to be spent on energy purchased from Russia by the end of 2025, ₽650 million ($8.4 million).

‘The main task is to get through the autumn-winter period with minimal electricity deficit’, Prime Minister Vladimir Delba stated at a meeting at the Energy Security Headquarters in September 2025.

Given the array of factors aligned against this goal, it remains unclear if they will succeed.

Politics and energy are inseparable

Energy has remained arguably the most pressing issue in politics in Abkhazia.

Every year during winter, the problem reappears, and successive administrations appear to be stumped on how to deal with it. Raising costs for domestic consumers, one of the more obvious solutions, time after time causes a societal backlash, but all other methods have fallen short of ensuring an uninterrupted supply of energy throughout the cold months.

Over 80% of the power infrastructure is in a near-emergency state, leading to a high percentage of electricity losses, First Deputy Prime Minister Dzhansukh Nanba said in an interview with Abkhazian Television in November 2024.

‘According to current data, losses in our systems will be approximately 25%-27% by 2024. This is a colossal level of loss’, Nanba said at the time. ‘This is practically the volume needed to cover our deficit’.

Abkhazia is not just a matter of occasional blackouts — it is a daily struggle that can leave virtually the entire population of the region shivering in their homes for months on end.

In November 2024, the yearly crisis began with four-hour daily power outages. Shortly after, the problem became so acute that authorities had to switch to a daily schedule of times when the power was on at all.

Starting on 9 December, electricity was supplied only twice a day — for just two hours and 20 minutes each time.

The issue was worsened by low water levels in the Ingur reservoir, leading to one of the primary sources of energy to be shut down as an emergency precaution.

As another temporary measure, approximately ₽600 million ($7.6 million) was allocated from the Abkhazian budget for commercial electricity flows from 1 November to 23 December.

These factors came against the backdrop of a massive political crisis in Abkhazia, concerning Russia — the other primary supplier of Abkhazia’s energy needs.

The crisis was prompted by a controversial piece of legislation that would have given Russian citizens preferential real estate opportunities in Abkhazia. What began as protests soon spiralled out of control, leading to the ultimate resignation of then-President Aslan Bzhaniya, in a move that was seen in Russia as a rebuke to Moscow.

Even after Bzhaniya resigned, Russia stayed the course, with Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova saying in December that the Kremlin expected Abkhazia to fulfill its allied obligations, including creating legislative conditions for Russian investments.

‘And we hope that the early presidential elections scheduled for 15 February 2025 in Abkhazia will lead to the election of a leader who will continue to work closely with our country on issues of Abkhazia’s progressive development and bilateral relations’, Zakharova added.

She also recalled that, guided by what she called humanitarian considerations, Russia increased the supply of energy to Abkhazia in response to an official request from then acting President Badra Gunba, who ultimately was elected.

Moscow is widely believed to have tipped the scales in favour of Gunba, and his election raised hopes that Russia would help resolve the expected deficit in the winter of 2025.

While Russia may actually follow through this pledge to relieve Abkhazians this winter, it has raised fears that Moscow could use the supply of energy as a carrot — or a stick — to ensure that the government in Abkhazia remains compliant.

Intersecting energy interests

To make matters more complicated, the supply of energy to Abkhazia is not just dependent on Russia.

The main source of electricity to Abkhazia comes from the Ingur HPP, located on the River Ingur.

It is the largest hydroelectric power plant in the South Caucasus, commissioned during Soviet times in 1978. The hydroelectric generators are on the Abkhazian side, while the dam (standing at 271.5 metres high, one of the tallest in the world) and reservoir are on the Georgian side. The facility is jointly operated between the Abkhazian and Georgian governments, and, according to an unwritten agreement, electricity is distributed as follows: 60% to the Georgian side and 40% to the Abkhazian side. However, in recent years, Abkhazia’s share has increased to 100% during the winter period.

Throughout the post-war years, Abkhazia received electricity from the Ingur HPP free of charge. Only one differential hydroelectric power plant is in operation — HPP-1, while the other three don’t work.

The capacity of each of the three differential hydroelectric power plants is 40 megawatts, and while their restoration could improve the energy situation, the government does not have the funds for this.

As Energy Minister Batal Mushba reported during a government meeting in parliament, two investment projects for run-of-river hydropower plants have been under development for two years, but their current status, as well as the date of their estimated completion, is unknown.

Mushba claimed that the Economy Ministry has short-term goals to ensure electricity supply to consumers, as well the long-term goals of multi-billion dollar investments to create generating capacity.

In 2021, the Ingur HPP’s diversion tunnel was repaired, costing €45 million ($52 million). During the period of repairs, from 20 January to the beginning of May, the plant was not operational. Of the total budget, €7 million ($8 million) was allocated as a grant from the European Commission, and a loan of €38 million ($44 million) was provided by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Even in the best-case scenario, in which the plant is fully repaired and operational, the facility is still largely constrained by environmental factors beyond human control.

A lack of water in the Jvari reservoir has regularly caused the Ingur HPP to stop functioning.

As of 1 November, the water level in the reservoir was 56 metres higher than at the same time in 2024. As Mushba explained, this was because more money was allocated this year to purchase energy from Russia.

The domestic factor

On top of the external factors, there are domestic issues that further complicate the government’s ability to stabilise the energy supply — namely the vast proliferation of illegal cryptocurrency mining (by some measures, accounting for most of Abkhazia’s energy usage), corruption, and the simple fact that the bulk of the population does not pay their electricity bills.

As of the end of October 2025, the payment collection rate for consumed electricity was 54%. For legal entities, it was 78%, and for individuals, 37%. According to current tariffs, individuals pay ₽1.7 ($0.02) per kilowatt-hour, while legal entities pay ₽3.2 ($0.04) — a significantly subsidised rate. By comparison, the average fee per kilowatt-hour in the EU is €0.28 ($0.32).

The government has reiterated that energy prices for domestic consumers should be raised, but given the low payment rate, and that much is siphoned off by illegal cryptocurrency miners who are unlikely to follow the law, it is unclear how this will solve the problem.

Cryptocurrency mining was banned back in 2020, but the regulations do not appear to have stemmed the spread of the practice, illustrated by the fact that previous government-mandated power cuts did not reduce the total usage of energy. Large mines have begun developing methods to avoid detection, while smaller ones operate off the grid.

An employee of the state-run energy company Chernomorenergo told OC Media in December 2024 that government efforts had largely failed to combat illegal cryptocurrency mining. At the time, acting Prime Minister Valery Bganba publicly called on miners to curtail their work, appealing to them personally.

In light of this, there is a sense of unfairness among some residents, that they are being asked to pay more while the real culprit continues to operate scot-free.

The opposition to raising the fees has been echoed by many in civil society.

In an interview with Abkhazian Television, Energy Minister Batal Mushba stated that electricity tariffs would rise from 1 January 2026. However, six opposition civil society and political organisations spoke out against the increase. In their joint statement, they claimed that ‘this step clearly demonstrates that the government’s policy is not aimed at supporting and developing society, but at further impoverishing the population’.

‘We strongly oppose the increase in electricity tariffs and demand that the government abandon this anti-people decision, which could lead to a new round of socio-political tension’, their statement read.

MP Beslan Khalvash, who opposes increasing tariffs for individuals, said that raising fees for individuals is simply infeasible.

‘We will consult here in parliament and develop solutions. Regarding legal entities, the issue of increasing payment can still be considered, but as for individuals, we have reached the limit for today’, Khalvash said on 20 November.

Similar sentiments have been expressed by public figures, such as Tengiz Dhzopua, who wrote on social media that ‘the economic policy implemented by the authorities always serves someone’s interests. Always. And not always in the interests of society or even the interests of large business groups in the country’.

He added that ‘when declaring tariff increases, the authorities are in no hurry to announce cuts in administrative expenses, and no one has mentioned a word about tightening payment collection among consumers, or, in short, about strengthening financial discipline within the power system itself’.

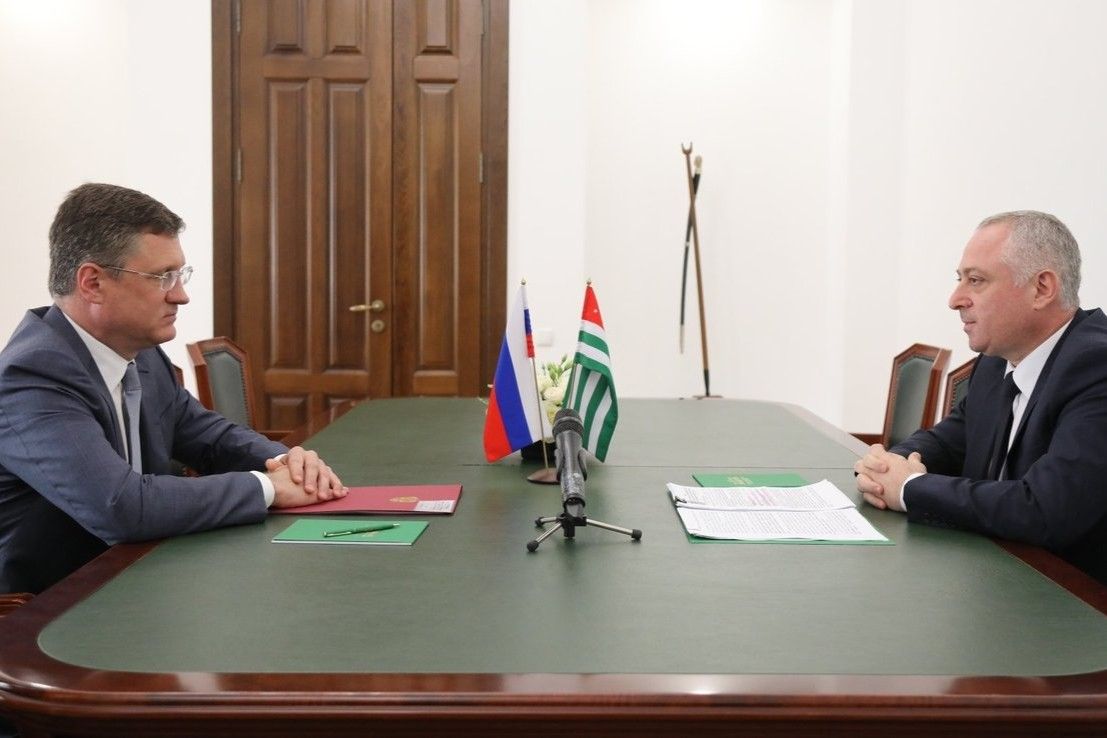

During a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin shortly after his election In March 2025, Gunba requested support for the development of Abkhazia’s energy sector, to which the Kremlin pledged assistance. Some of this material support has since come through, but the issue has remained a key factor in relations between Abkhazia and Russia.

But even this Dzhopua asserted, comes with a cost.

‘At the core of the Abkhazian understanding of the economy is an exclusively fiscal demand. The import of electricity flows from Russia drains the financial and political resources of the authorities. Both hit, first and foremost, the interests of the authorities themselves — they want a bit of freedom and at least the feeling of some kind of self-sufficiency, however illusory. I’m not talking about Abkhazia’s economic sovereignty but rather about at least some minor political “sovereignty” of a vassal before its suzerain. Abkhazian politicians may no longer feel ashamed to be on their knees, but their knees hurt.’

And without systematic change — expensive repairs, a crackdown on cryptocurrency mining, or significantly increased enforcement of electricity fees, Abkhazia will likely continue to face a similar situation in 2026 nonetheless.

‘During a crisis, the state attempts to influence economic processes with various tools: fiscal, monetary, budgetary, foreign-trade. From this whole set, we only know how to use a hammer and a saw: to hit and to cut. Everything else is either too difficult for us or impossible. […] But even in matters of fiscal, budgetary, tax, and foreign-trade policy, we do everything exactly the opposite of what common sense would dictate’, Dzhopua said.

‘So nothing is changing. Only the faces change — they have become younger and more attractive. That’s where the changes end’.

All place names and terminology used in this article are the words of the author alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.