‘A personal catastrophe’ — Roza Dunaeva on Europe’s deportation of Chechens

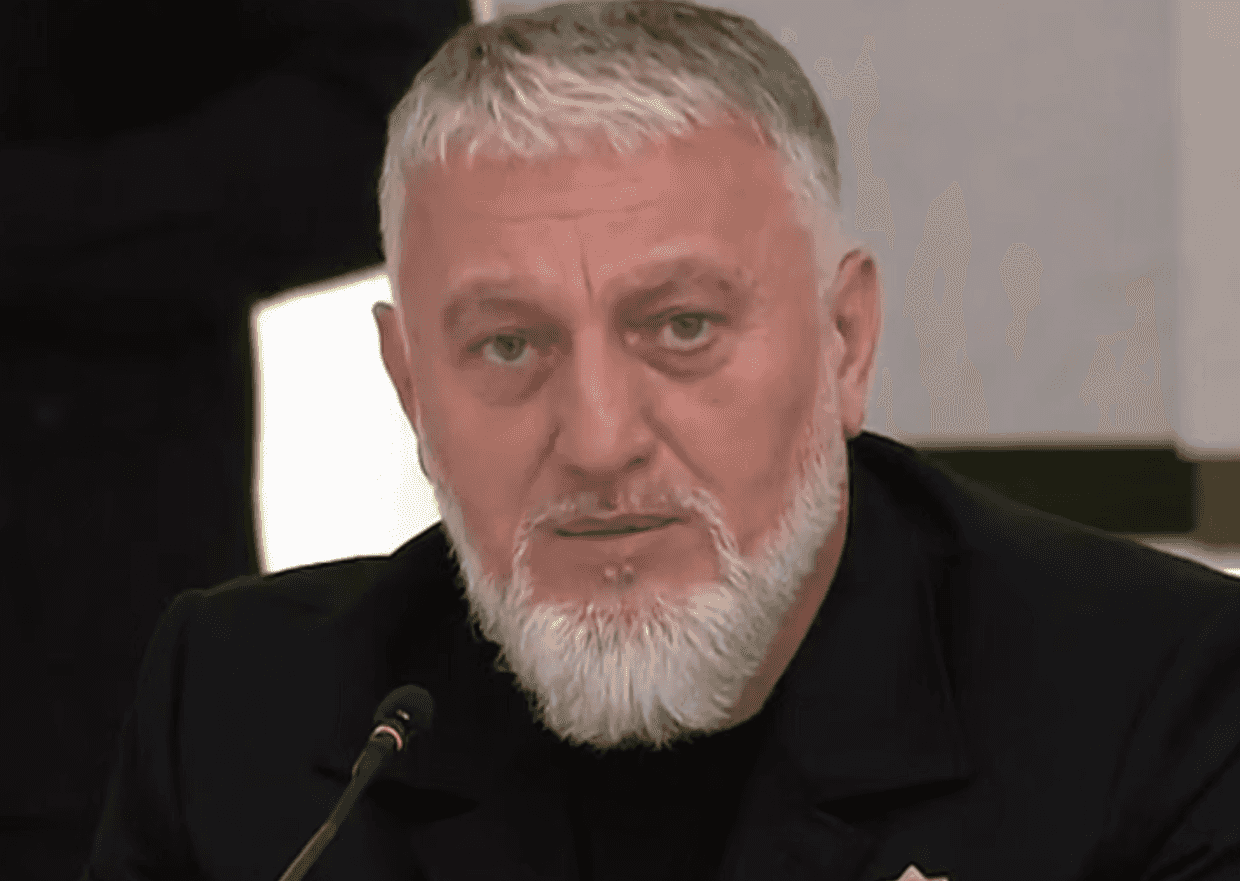

Roza Dunaeva, a representative of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria in Austria, has spent years highlighting the cases of Chechens deported to Russia.

After 12 years of fighting, the Second Chechen War officially ended in 2009. Yet the conflict left deep scars — an entire decade of death, disappearing cities and villages, and shattered families. Children were born into war, boys became men too soon, and whole generations grew up in the shadow of violence. Those who refused to join the Russian side were forced to leave their homeland and seek a new life in exile, watching from afar as their native land slowly turned into an extended arm of the Kremlin.

Roza Dunaeva, a representative of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria in Austria, is a mother of the next generation that has grown up abroad. Yet she herself has never forgotten what it means to be Chechen — and the risks it entails.

‘I see [Chechen youth] every day — growing up, learning, dreaming, and planning their futures. They speak several languages, have embraced the culture of this country, and consider it their home. Yet I also see how their lives can collapse in a single moment’, she tells OC Media.

Dunaeva has dedicated herself to raising awareness of the cases of Chechens deported to Russia, something that has continued despite repeated warnings by activists that they face persecution, and even death if they go back.

‘One by one, the boys are taken away and sent to Russia; what remains are broken families, fear, and the cries of mothers. These children grew up here, received their education here, Austria is their second homeland — and yet they are being sent back. That is a betrayal. Either accept us as equals or treat us humanely’, she says.

She argues that instead, European countries should give the new generations a chance to live, learn, and work in the society to which they already belong.

‘We do not live in a dictatorship but in a democracy — so we have the right to speak out. Punish justly, but do not hand people over to a place where they face destruction’.

Dunaeva describes the process of deportation as, above all, a personal catastrophe.

‘A person has served their sentence, realised their mistakes, tried to build a normal life — they have a family, friends, education, they are integrated into society — and then suddenly, they receive a deportation notice literally a day before they are taken away’, she says emphasising that the current legislation does not take social rehabilitation into account.

‘For us, who fled war and violence, this is effectively a handover into the hands of the FSB system and the occupation administration. Europe knows this. This is not only about law — it’s about humanity. For the person themselves, it feels like complete betrayal: they have built a life, tried to become part of society, and now they are seen as a threat or a problem that simply needs to be “removed” ’.

Dunaeva emphasises that many countries do not understand, or do not wish to understand, the situation on the ground, telling activists that ‘there is no danger in Russia’.

‘For Chechens, that is false — and a deadly risk’, she says.

While in the past, the EU acted according to UN standards, Dunaeva argues that today it signs agreements with official Russian structures, labelling the situation: ‘safe’, despite evidence to the contrary. She believes this is due in large part to changing political and economic interests, including trade and energy. In any case, one result of this is that Chechen applicants are advised to extend their visas at Russian embassies and otherwise have contact with Russian state structures, which can be ‘fatally dangerous’.

Dunaeva uses the case of Umar Bibulatov as an example of this:

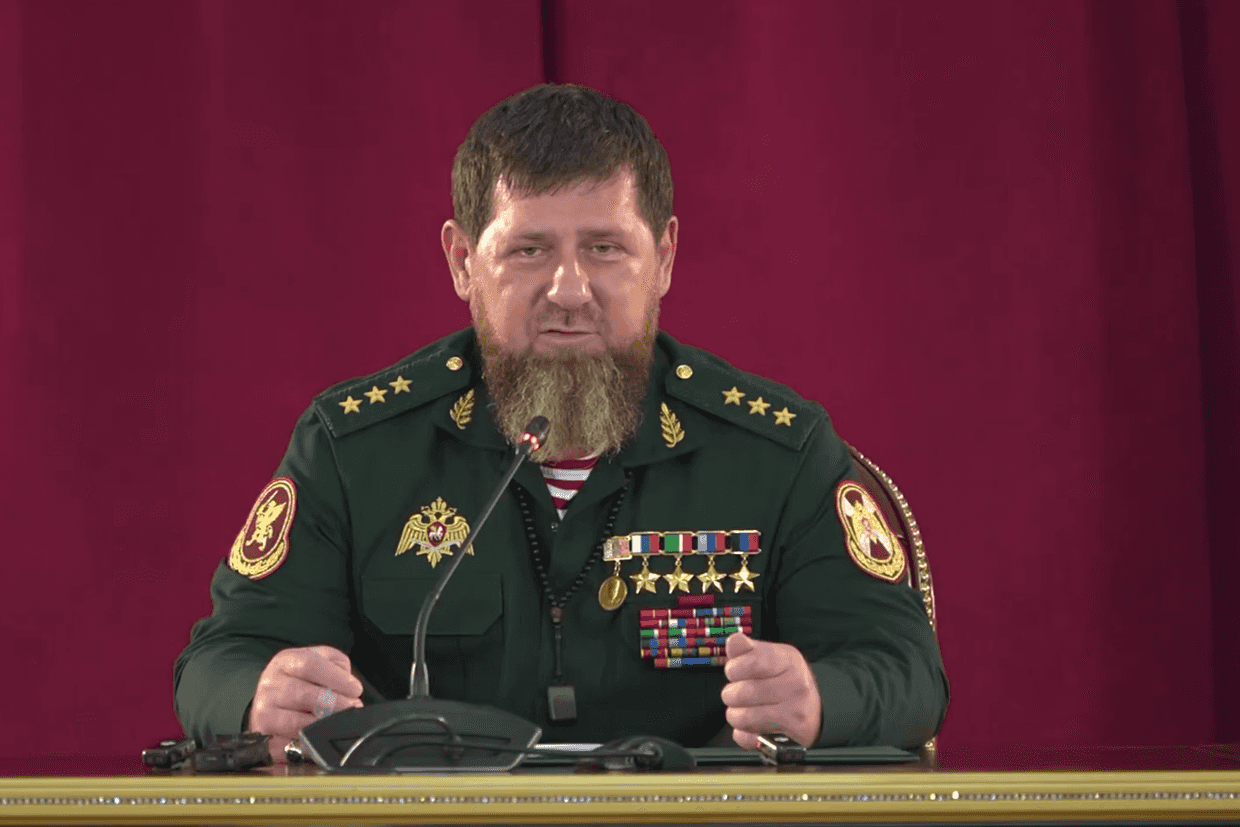

‘He was deported from Austria, then from Germany, handed over to Russian security forces, who then passed him to [Chechen Head Ramzan] Kadyrov’s men. He was “fined”, and in the end, sent to the front against Ukraine, where he was killed’.

Dunaeva highlights that Bibulatov’s case was not an exception, but ‘part of a chain of tragedies’.

‘Behind these decisions stand political, bureaucratic, and economic factors — and the ignorance of the real risk of torture and forced mobilisation. People who fled violence are being turned into weapons in foreign wars’.

While Dunaeva believes there is still a chance for change, she emphasises it must come as real action, not just on paper.

‘If Europe stands for democracy and human rights, it must stand with the Chechen nation, discuss the Chechen question, and provide protection. Today, it is unacceptable to hand Chechens over to Russia or to leave the North Caucasus without protection. Otherwise, Europe becomes an accomplice. If it wants to remain true to its values, it must stop this practice’.

She is particularly pained by the behaviour of some lawyers:

‘They take money, promise help, and reassure people that according to the law everything can be resolved, because the case is clear — where there is guilt and where there isn’t. If a person is in danger, they must not be deported — that is written in the law. But as soon as the lawyer receives a certain “signal” or pressure, they disappear’, Dunaeva says.

She argues that behind certain legal phrases, such as a ‘threat to public safety’ or ‘previous convictions’, lies an attempt to avoid tension. In practice, she says, these mechanisms are applied selectively — within the Chechen diaspora, this creates the feeling that Chechens have become nothing more than a bargaining chip in great power politics.

Indeed, Dunaeva notes that tools such as Interpol notices and extradition requests are often being misused, citing repeated cases in Bosnia and Herzegovina where Chechen refugees were detained on what was later determined to be fabricated and politically motivated charges.

‘These are not isolated incidents but a systemic problem encountered by lawyers, judges, and human rights activists. Moreover, similar requests are made even against people who have lived in European countries for 20–25 years, hold citizenship, are fully integrated, and have never faced criminal prosecution. Yet they are forced to undergo new court processes and face pressure and fear’.

Dunaeva also notes with disappointment how deeply silence is rooted within the system.

‘Intelligence services possess a great deal of information, but most of it remains classified. European countries avoid direct confrontation with Russia over issues they consider “secondary”, and the protection of Chechen political refugees is often sacrificed to diplomatic interests’, she says.

She argues that such intelligence agencies are certainly monitoring networks connected to Kadyrov, but says this information is rarely made public, given that it is considered to be part of ‘ongoing operational processes’.

Although Kadyrov’s agents rarely appear openly in Europe, their presence is palpable, she says. They operate mostly in the background — through investments, business, and cultural events that serve as instruments of soft power. The older generation in the diaspora perceives these connections more sensitively, while the younger ones focus more on education, work, and integration into society.

‘When Russian artists who support the occupation [of Ukraine] come to Europe, we organise protests — because there must be no place for propaganda here’, she adds.

Dunaeva also believes that European states are striving to keep communication channels with Moscow open, with deportations sometimes operating as ‘a quiet political signal of loyalty or neutrality.’

‘Silence is not ignorance — it is a strategy,’ she says. ‘The political benefits of inaction often outweigh the risks of breaking that silence. But we understand very well how international politics works — the fate of small nations is often subordinated to the interests of the great powers’.

Even so, Dunaeva emphasises that she, and other activists, continue.

‘We document persecution, apply for political refugee status, appeal to EU and UN human rights bodies, and involve independent media and legal networks. This is our way of remaining visible — and of not disappearing into silence’.

As she puts it: ‘We have made our choice’.

‘We often have no direct contact with our closest ones; we only learn that they are still alive. We feel their pain, as well as the pain of the entire nation. We fight for the sake of future generations. This struggle is not just a word or an idea. It is life, it is hope, it is the longing for freedom. And we will continue it, no matter what happens’.