With universities and research institutes failing to attract young people, the sciences in Armenia are becoming the realm of the aged. But could a boost to funding, opportunities to study abroad, and attracting foreign scholars reverse the demographic trends in the country’s ageing sciences?

In a small classroom at Yerevan State University’s Faculty of Physics, Hrachya Asatryan tells a group of teenagers about black holes, the structure of the solar system, and what exactly a ‘light-year’ is. The students sit silently, with rapt attention.

Asatryan, who is studying for a Master’s degree in Physics at Yerevan State University, is teaching the youngsters not only because he has a passion for physics, but because he wants to inspire those same feelings in the younger generation.

If they don’t become Armenia’s next generation of physicists, who will? This is not an abstract question for someone like Hrachya — out of five master’s students who joined the department of theoretical physics along with Hrachya, he is one of only two who remains; the rest dropped out or went to study abroad.

His experience is emblematic of a wider crisis facing the sciences in Armenia, with a lack of students resulting in empty lecture halls, unfilled jobs, and a community of scientists that is quite literally dying out.

Hrachya has loved physics since his school years; both his father and grandfather are also theoretical physicists, and his grandfather was once the director of the Alikhanyan National Laboratory. He says he wants to pursue a career in science despite the lack of financial rewards.

‘Adults say that when you do something you don’t like, you won’t last long: you have to do what you love, then your job won’t be a duty for you.’

Declining opportunities

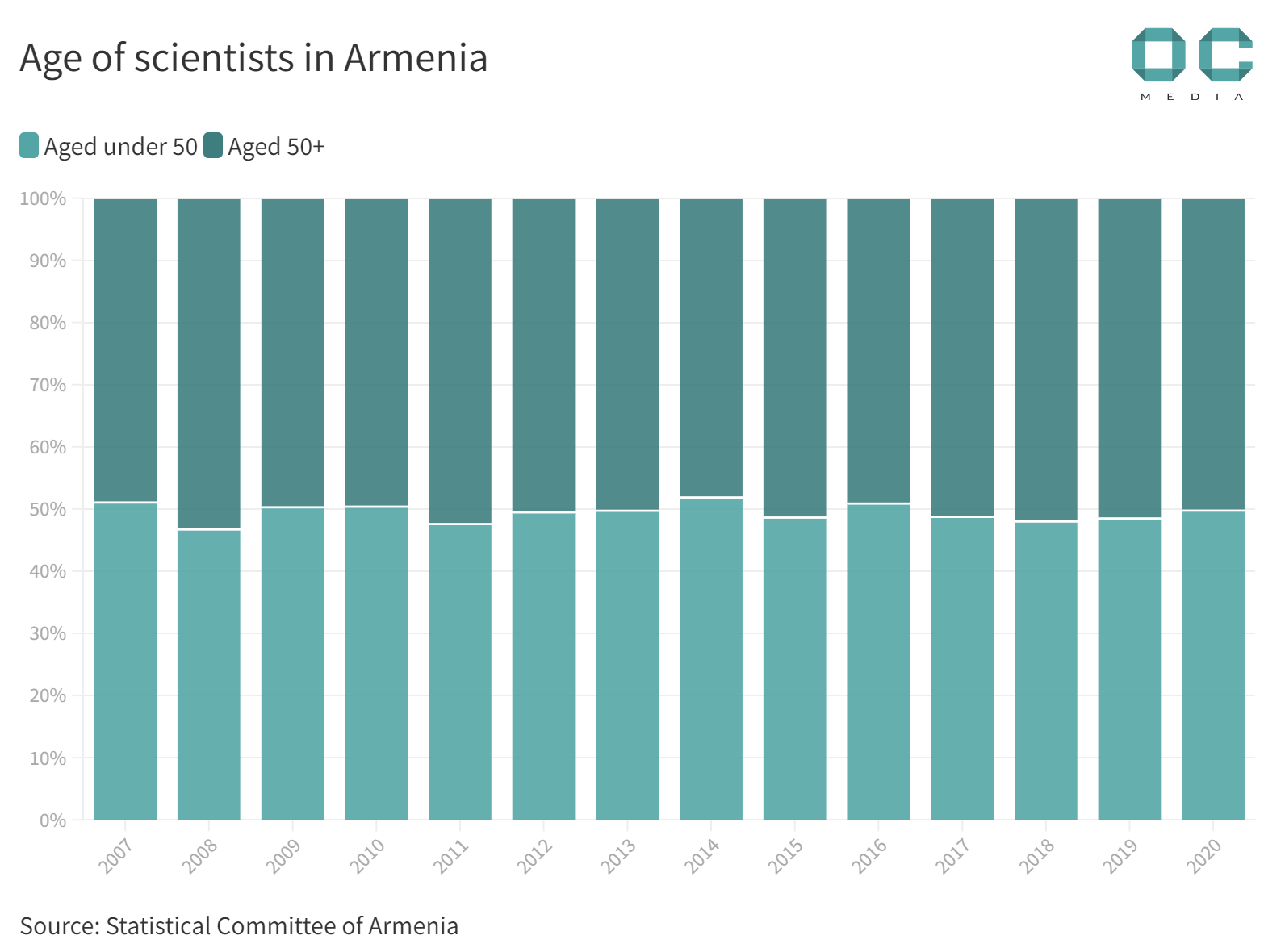

According to data from the Statistical Committee of Armenia, in 2020, more than half of scientists in Armenia were over 50 years old; a figure that has remained practically unchanged since 2007.

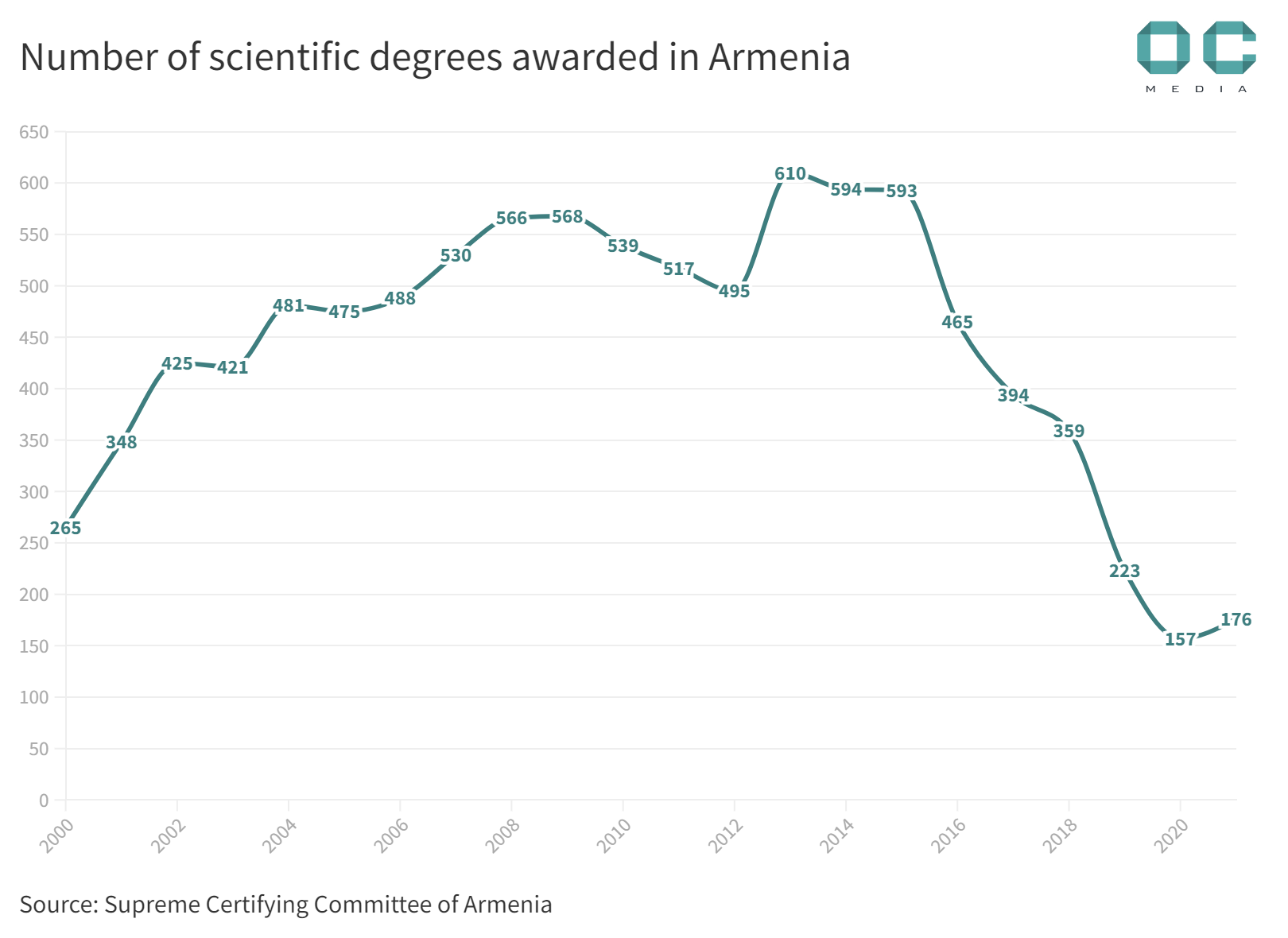

The scope of the crisis was stressed by Karen Keryan, Chair of the Supreme Certifying Committee of Armenia (SCC), which is responsible for certifying scientific degrees in the country. In a 2021 press conference, Keryan warned that the number of graduating students was ‘not even enough to replace the last generation of scientists and replenish the teaching staff’.

According to the SCC, the number of doctorates awarded across all fields has precipitously dropped in recent years, with 70% fewer students receiving doctorates in 2021 as compared to 2016.

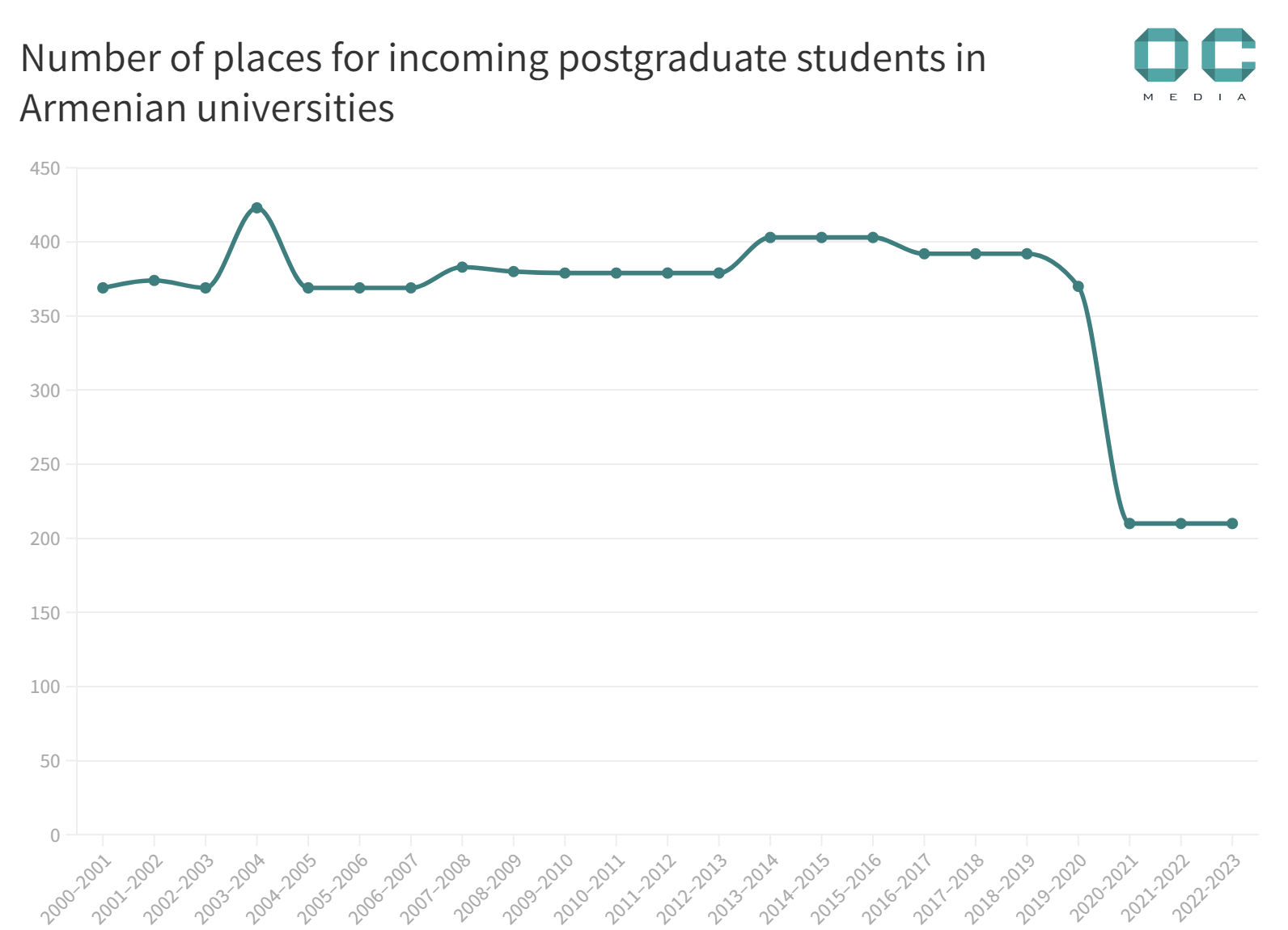

The Gituzh initiative, which periodically voices the problems of science in Armenia and offers solutions, called for increasing the number of places in doctoral education this year. However, the government has left the number of new places for postgraduate education unchanged.

There is also the issue of pay. Postgraduate bursaries in Armenia are low, with the highest scholarship available just ֏65,000 ($160) per month. Prior to 2020, this figure was less than half that.

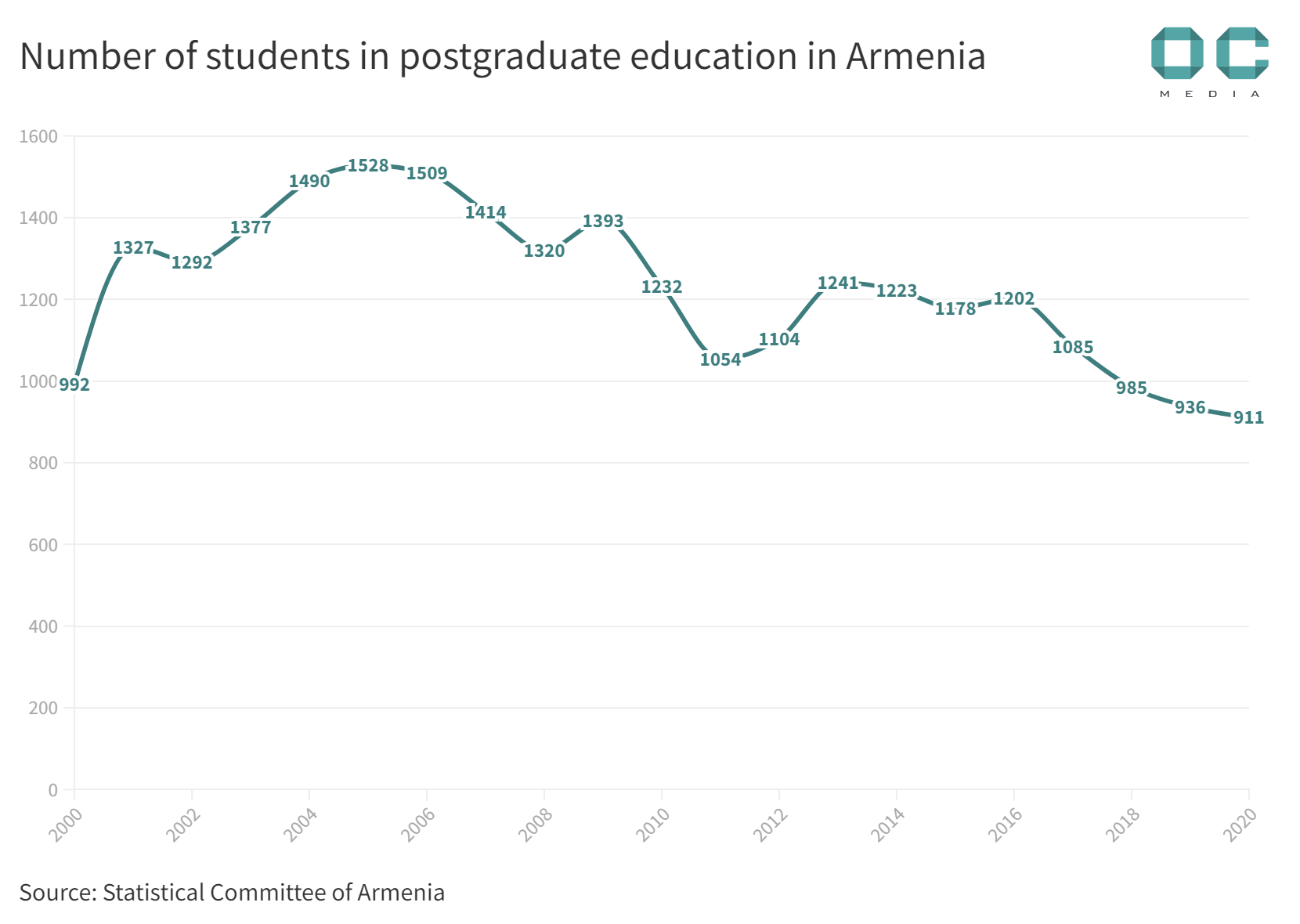

The number of postgraduate students has also decreased in recent years. In the early 2000s, some years saw the number of students pursuing postgraduate degrees at any one time reaching over 1,500; In 2020, there were only 911.

Structural problems

Hrant Khachatrian, director of the YerevaNN machine learning research lab, identifies more than university policy as the cause of the current shortage of young scientists.

One major reason he cites is that state-run scientific organisations in Armenia keep on older employees out of a sense of obligation.

‘If there is someone who has devoted their life to science for many years and today, perhaps, doesn’t work so effectively, the institute takes responsibility for ensuring the social status of these people’, he explains. ‘Because, for example, pensions in the country are low, and if you leave these people only on pensions, it would not be right.’

‘Scientific growth potential is not the most important factor in the allocation of staff or financial resources within the institute’.

Khachatrian says that it’s difficult to blame managers for such social or emotional approaches. But, he says that not all scientific institutes have the same situation — there are some in which the percentage of younger scientists is quite high․

‘This is because managers find some ways to direct funds to promising young people. But in many places, this problem is not even raised, and this leads to the fact that [institutes] have great difficulty hiring young people’, he says.

Young people see that many institutions will not provide them with a decent career path, Khachatrian says, which contributes to them choosing another career or emigrating.

Steps forward?

In an attempt to reverse the trends, the scientific community in Armenia has for years raised the problem of insufficient funding for science. The approach may be bearing fruit. This year, the government raised the salaries of researchers, promising to continue to increase them gradually through to 2025.

According to Khachatrian, these are the right messages, and many young people are beginning to see that there may be opportunities opening up in the sciences. But, he says, these steps have not yet had much of an impact.

Artur Movsisyan, the Deputy Chair of the Science Committee at the Ministry of Education and Science, Culture, and Sports told OC Media that on top of the low salaries, the dilapidated state of research institutions and shortages of scientific equipment also posed a problem.

Movsisyan said that increasing grant funding at every stage — from education through to late career — would be a powerful tool to increase the retention of young scientists in the country.

Steps in this direction have already been made — since 2020, the government budget for grants has increased by a factor of four.

There have also been moves to bring international scientists to Armenia. This year, the Science Committee announced a series of international grants. The main targets of this funding are postdoctoral researchers, who are eligible for five-year grants to work as guest researchers at any scientific institute in Armenia. Another grant is available for foreign scientists to form groups in Armenia, and then lead them remotely.

The capacities of host organisations to welcome these guests, however, may remain an issue.

‘There is an idea that, perhaps, it is not necessary to limit this only to existing institutions, but it is possible to try to create opportunities for the creation of new scientific structures that are not poorly managed’, Khachatrian told OC Media, adding that scientific funding was also not yet competitive for non-Armenians.

To address this problem, the Science Committee is implementing two programmes aimed at sending postgraduate students and post-doctoral researchers abroad, provided they return to work in Armenia.

According to Artur Movsisyan, they want to ensure that 60 people are sent a year by 2025.

The goal, Movisisyan said, is to integrate into the European scientific community — and to bring the sciences in Armenia up to the standards of the average European country.

For now, for many of the young people pursuing science in Armenia, passion and a wish to change things for the better are the main motivators.

Lilit Nersisyan studied biology against the advice of her parents — both biologists — who saw little opportunity in their field. After completing a postdoc in Sweden, Nersisyan returned to Armenia and established the Bioinformatics Institute, which both conducts research and is training a new generation of researchers.

Lilit hopes that their institute will be able to create an environment that will attract foreign scientists to come to Armenia to pursue a postdoc or lead scientific groups, with this attract more young scientists.

‘I realised that doing science alone, writing articles alone, creating scientific innovations alone without social consequences is not something of interest to me’, says Nersisyan.