Armenia’s housing policy continues to plague Nagorno-Karabakh refugees

Two years on, Nagorno-Karabakh refugees still struggle to navigate Armenia’s housing programme and successfully rebuild their lives.

When Arevik Balyan fled her hometown of Chartar (Guneychartar) in 2023, following Azerbaijan’s last large-scale military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh, she hoped to rebuild her life in Armenia.

‘I lived normally in my house in Chartar. We had a rural economy, but I worked as a cleaner at an art school in my hometown — we didn’t want for anything’, Balyan says of her past.

Following the mass exodus, she and her family found a new home in Yerevan. Recently, however, she received an ‘unexpected’ phone call from the owner asking her to vacate the house.

‘Now we are forced to find something else. I just want to be close to my son’, she says.

Both her son and brother were killed during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and are buried in the Yerablur military cemetery on the outskirts of Yerevan.

‘My husband and I have health issues and we want to be close to our son’s grave so that we can visit him’, she adds.

Like many refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh, Balyan relies on government support, particularly in regards to housing.

In May 2024, the Armenian government approved a programme providing the refugees with vouchers worth ֏2 million–֏5 million ($5,200-$13,000) each to spend on housing, depending on where they choose to settle. The largest funds are given to those choosing to live in settlements near the border with Azerbaijan or in remote areas.

Many Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh have criticised the programme for its emphasis on residing in rural areas, outside of the capital Yerevan where most jobs and educational opportunities are. The fact money is given per family member also gives larger families an advantage, which some don’t believe is equitable.

While criticisms abound, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has repeatedly denied that Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians are once again facing the threat of being deprived of their homes.

‘I absolutely deny it, there is no such thing. The programme has been opened for all our sisters and brothers by the latest government decision, and people can take advantage of the programme’, Pashinyan said in July.

Separately, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs has reported that as of 9 October, over 3,000 families had received vouchers within the programme, of whom over 1,050 had already used them.

‘May everyone’s family have six members’

According to Labour and Social Affairs Minister Zara Manucharyan, the amount given is more than sufficient, even allowing people to buy furniture and appliances with the surplus.

‘If a family with six members plans to build a house in a settlement that provides for ֏5,000,000 ($13,000), they will be provided with ֏30,000,000 ($78,000)’, Manucharyan said in a video message in July.

Yet the programme remains inaccessible to many, says Lianna Petrosyan, an activist from Nagorno-Karabakh. She notes that around half of those who have received vouchers have been unable to use them, for various reasons.

‘This programme does not work for small families — there should be another, additional option so that small families have the opportunity to purchase an apartment’, Petrosyan tells OC Media.

Balyan agrees, noting that she only has a three-person household since her other daughter got married and her son began studying medicine in Moscow.

‘Since the assistance programme was cut, it means that only my 12-year-old daughter will receive ֏30,000 ($80). What should we do with that?’, she asks.

In the spring, the eligibility criteria for a separate government assistance programme for the refugees was adjusted, excluding most working age people, while the monthly assistance was gradually reduced from ֏50,000 ($130) to ֏30,000 ($80). From 29 March, ahead of the date the reductions were supposed to begin, Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians held a series of protests, which eventually ended in July without achieving results.

Balyan emphasises that even though she is under the supervision of doctors, due to ongoing problems with her health, she still works as a cleaner in a canteen as her husband is not able to work at all. Besides earning for her own household, her wage also goes towards covering the expenses of her son in Moscow — she sends him ֏200,000 ($520) every month.

‘May God protect everyone’s children, may everyone’s family have six members — but when it turns out that there are too few of us in our family, do we have to suffer unfairly like this?’, Balyan asks.

‘I’m already going crazy, this situation is simply destroying what remains of my health’, she says.

Laura, a retired journalist who spent 40 years working and living in Nagorno-Karabakh, who did not wish to give her last name, also questions the government’s assumption that families from Nagorno-Karabakh all had six members.

‘That’s a really painful question for me. Tell me, please, how can I benefit from this programme?’, she asks.

Laura lives with her daughter, who earns a salary of only ֏140,000 ($365) per month, which barely covers their rent, let alone other expenses.

‘How can we buy a home with the ֏5,000,000 that they suggest?’, Laura asks.

‘How can a father of seven not worry?

In 2020, when Shushi (Shusha) came under Azerbaijani control, Karen and Lilit moved to Stepanakert, also in Nagorno-Karabakh where they at first lived with Lilit’s mother and relatives in a rural house in the city suburbs.

At the time, families were given $4,000 by the now-detained Russian–Armenian billionaire Samvel Karapetyan when their fourth child was born — later, his nephew Narek Karapetyan announced that if a fifth child was born, the family would be given an apartment.

‘It so happened that I took advantage of both charity programmes at that time’, Lilit says, adding with a laugh that she was told she could point her index finger at any apartment in Stepanakert and it would be hers.

Eventually, they were given an apartment in a newly-constructed building right in the city centre. Not even a year later, however, they were forced to leave the apartment, and Nagorno-Karabakh as a whole, in the mass exodus.

‘I can’t watch the videos posted by Azerbaijanis on social media from Stepanakert. How long did I have to fight, struggle against the government, until we got that apartment? My heart is breaking’, Karen says.

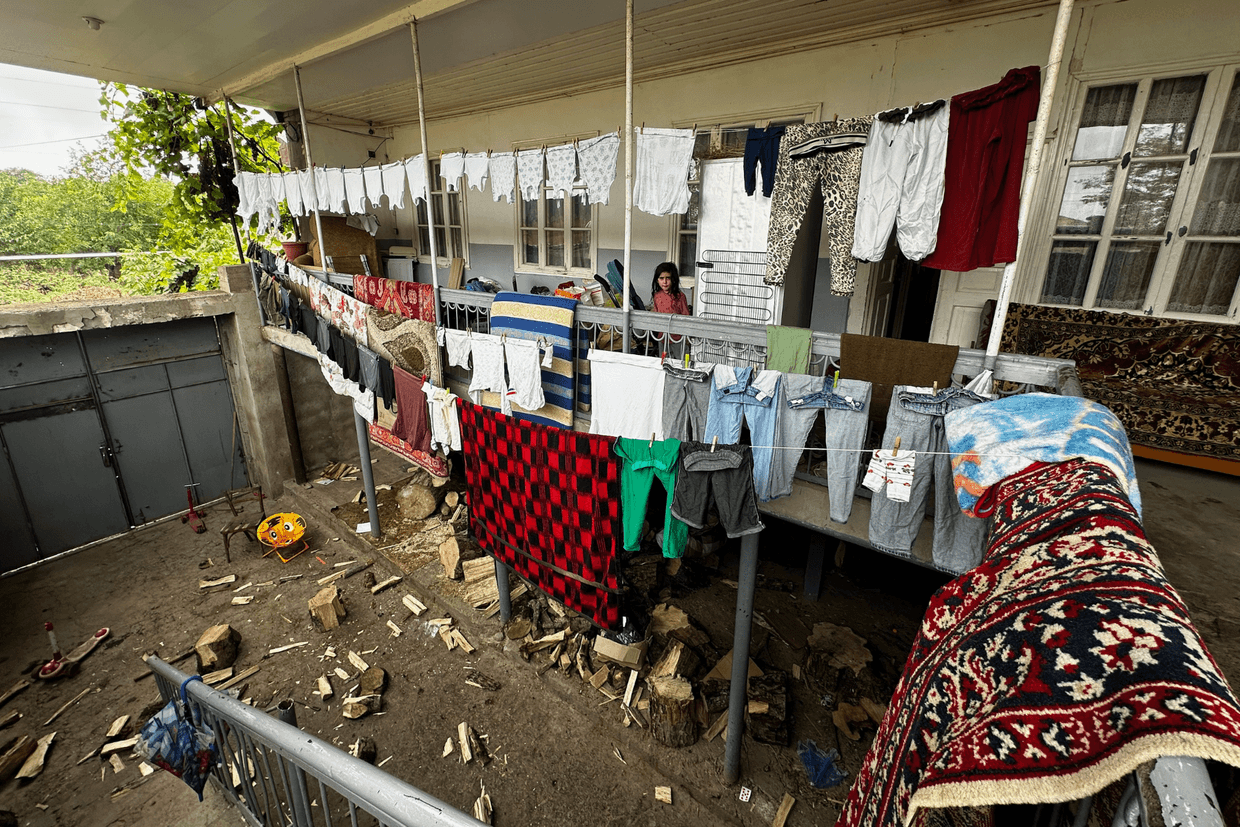

The couple, now with seven kids, first rented a house in Armenia’s southern border village of Tegh, but the conditions were poor.

‘Mice were running over the children’s clothes in the closet and bed, the walls weren’t even plastered. It was terrible, especially in winter’, Lilit says.

Karen adds that it gets as cold in Tegh as in Nagorno-Karabakh — they paid ֏160,000 ($420) for gas last winter.

‘The baby was just born, what could we do? He would get sick’, Karen says.

The family eventually moved to a slightly larger house in the same village, which, as Lilit says, ‘isn’t fancy either, as you can see, but at least there’s room to move around here’.

‘I have many children. What can we do? The whole month we are waiting for those two coins from the government to cover our expenses’, she says.

Preparing for the winter again, the family has already bought a square metre’s worth of firewood for their new house, costing ֏23,0000 ($60), but Karen believes they will need more. He also struggles with his health, making it hard to do the household chores.

‘I can’t chop [the wood], my children do. But I am scared that when they hold the axe, they could harm themselves’.

His doctors have diagnosed him with intervertebral disc disease, a condition characterised by the degeneration of one or more of the discs that separate the spinal bones, causing back and neck pain, and often pain in the legs and arms.

‘My wife has called the ambulance so much that they already recognise her voice, and immediately park in our yard’, Karen says.

‘They say that the cause of all these illnesses is anxiety, but how can a father of seven not worry?’.

He says that when they were still in Nagorno-Karabakh, they never suffered from any serious illnesses. It was only once they became refugees in Armenia that the troubles started.

‘There isn’t even a single pharmacy in the village — we regularly go to Yerevan to see doctors. There are so many troubles that I don’t know which one to think about’, Karen says.

Apart from the pharmacy, there are also no shops for household items, nor a supermarket. Locals often borrow goods and only pay at the end of the month once they receive a pension or salary.

Tegh is also considered a military buffer zone — locals recall that until 8 August and the initialling of the peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan, it was not uncommon to hear sounds of artillery fire or shelling.

Yet, Lilit and Karen prefer it over Yerevan, not just because Lilit’s mother and sister are based here as well.

‘From [my mother’s] kitchen window, Lachin is clearly visible at night when the electric lights are on over there. We experience great longing and pain as we look towards Nagorno-Karabakh’, Lilit says.

This article was translated into Russian and republished by our partner Jnews.