Georgian watchdog groups are becoming increasingly worried about bogus user accounts that frequently praise the government and target their critics, especially in times critical for the ruling Georgian Dream Party. Negative campaigns, online trolls, and fake news agencies, which dominated the last presidential election and indicated murky campaign finances, have now become a part of daily political news.

The backlash from residents of Pankisi Valley against the use of police force to secure a construction site for a new dam in the valley sparked heated debate among Georgians. But not all who actively engaged on Facebook to defend the police’s actions and reprimand residents of Pankisi and their supporters were authentic.

At least this is what the latest report from the Media Development Foundation (MDF), a Georgian watchdog group that monitors disinformation and their sources, suggests.

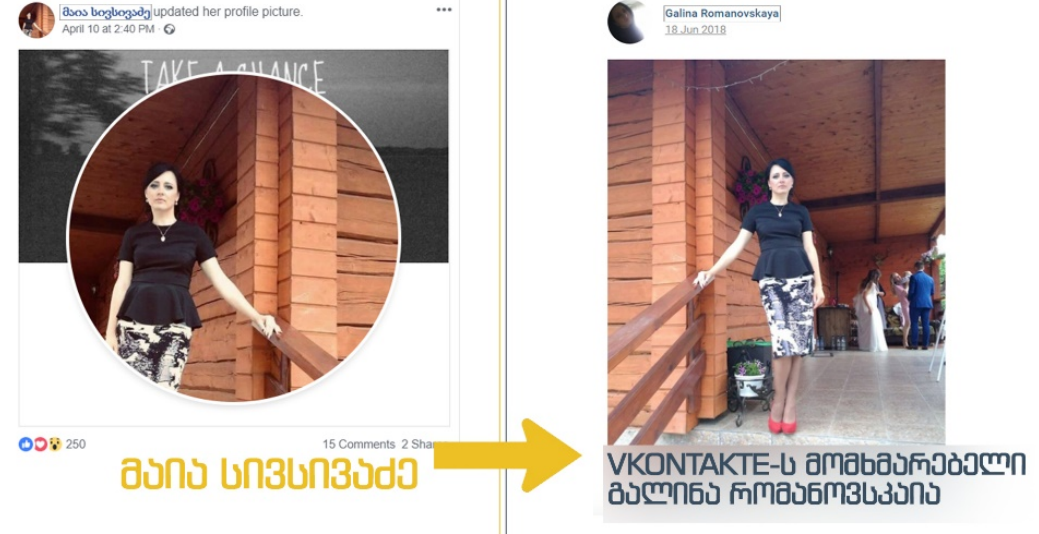

After looking closer at some of the Facebook users who tried to save face for the government online, MDF discovered seemingly fake accounts that used pictures of random people in their profiles.

These alleged trolls advocated for the Khadori 3 hydropower project planned in Pankisi Valley as safe for the environment and insisted it was necessary to ensure Georgia’s energy independence — identical to the current talking points of the Georgian government.

These Facebook accounts, according to MDF, actively distributed talking points from Ghia Abashidze, an expert frequently characterised by critics, including the former ruling party the United National Movement (UNM), as loyal to Georgian Dream.

Following the anti-police riot in Pankisi, Abashidze accused advocacy groups critical of the government’s policies in Pankisi of ‘spreading fake news’ and being alarmists over hydropower plants. His targets included rights group the Human Rights Education and Monitoring Centre and environmental group the Green Alternative, both of which have been highly critical of the government’s actions in the valley. He labelled a list of 20 non-governmental organisations ‘situational allies’ of the UNM.

Accounts suspected by MDF to be trolls also spread Islamophobic messages about Kists, an ethnic Chechen sub-group that makes up the overwhelming majority of the population of Pankisi, with some accusing them of separatism.

Hackers and trolls vs the banker: ‘investigation pending’

In early March, Mamuka Khazaradze, the founder of one of Georgia’s two largest banks, TBC, accused Georgian law enforcement agencies of failing to find the hackers that attacked his bank. According to Khazaradze, a security breach in the summer of 2018 coincided with the start of a probe into his bank by four state agencies.

According to letters made public by TV Pirveli in March, Khazaradze notified the authorities about the hacking on 17 July 2018.

According to his follow up letter to the interior ministry in mid-August, TBC’s IT team traced the origin of the Trojan virus they were infected with to an IP address associated with Gravity Ltd’s office located on Tbilisi’s Rustaveli Avenue. Speaking to lawmakers on 4 March, Khazaradze alleged that the office was likely home to the ‘bots and [troll] factories’ that had targeted him online.

According to Khazaradze, the trolling began several days after the Prosecutor’s Office publicly disclosed in mid-January that they were investigating him and his deputy.

The Interior Ministry has maintained that a ‘comprehensive’ investigation is underway, though no specific charges have been brought against anyone.

State-employed troll-masters?

Last summer, the UNM accused Shalva Ramishvili, an anchor at pro-government channel POSTV, of running a ‘troll factory’ from his office. In June, a month before TBC’s hacking, the UNM insisted that the journalist employed ‘about 200’ people working from their homes, instructing them to attack government critics online.

On 9 March, opposition-leaning TV channel Rustavi 2 claimed that Gravity Ltd’s office on Rustaveli was run by ‘Georgian Dream PR manager’ Koka Kandiashvili and the founder of POSTV Lasha Natsvlishvili, who is a former senior official who served under Georgian Dream.

These three individuals, all known as fierce critics of the UNM and third Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili, vehemently denied the allegations.

During the October–November 2018 presidential elections, it became apparent that following both IP addresses as well as money is key when it comes to Georgia’s cyber-world.

According to MDF, who followed the online anti-Khazaradze campaign closely in January and February, several of the pages and groups on Facebook ‘exposing’ the TBC founder were run by bogus accounts.

For instance, according to their report, one of the Facebook accounts actively engaged in the anti-TBC campaign online, which used a typical Georgian name, ‘Avtandil Kereselidze’, was fake, using images of Karo Manukyan, a random Armenian living in Yerevan. The account was later taken down by Facebook on Manukyan’s request.

Targets: government critics

Pankisi Kists and Khazaradze were among several other targets of negative Facebook pages. All of the targets shared one common feature: they all posed a problem for the Georgian government in one way or another.

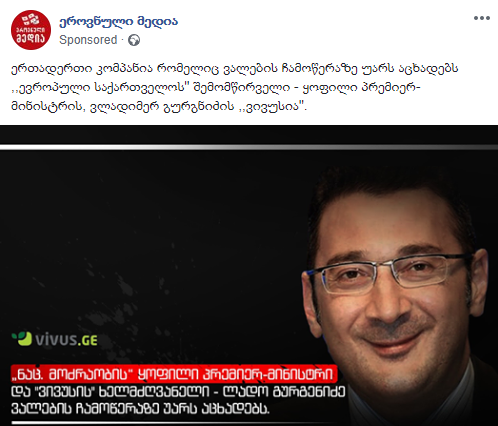

For example, Vivus.ge, a micro-credit lending company, was targetted by pages after they refused to sell their debts to Ivanishvili’s charity, the Cartu Foundation, as part of the Georgian government’s mass debt relief prior to the 2018 presidential elections.

According to the MDF report, these pages, most of them created in 2018, praised Georgian Dream officials and criticised political opposition groups and TV channel Rustavi 2.

MP Eka Beselia, the main target of recent sex tapes leaks — yet another ‘ongoing investigation’ into a cyber-crime — was also targeted by several Facebook pages.

They started ‘exposing her corruption’ right after her public fallout with the party secretary Irakli Kobakhidze in January, which was followed by Beselia’s departure from Georgian Dream.

Other targets have included prominent government critics such as Zaza Saralidze, whose son’s murder was never solved, and Nona Mikhelidze, the author of a September 2018 independent report to the European Parliament that was critical of Georgia’s democratic progress.

Both main parties have embraced fake news

Two out of the nine anti-Khazaradze Facebook pages were run by ‘Kereselidze’, who previously ran sponsored smear posts against presidential runner-up Grigol Vashadze, the UNM’s candidate.

A December report by ISFED noted the increase of new Facebook attack pages during the election campaign. From mid-October to late November, the peak of the campaign season, the number of such pages went from 54 to 160.

ISFED’s study suggests the camps of both presidential candidates benefited from, if not directed, the Facebook pages that tried to discredit their opposition: by the presidential run-off in November, there were 72 explicitly anti-Vashadze pages and 43 anti-Zurabishvili pages.

In a live Q&A session on Facebook on 20 December, former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili stated that Guram Donadze, a former public relations official at the Interior Ministry, and Parnaoz Chkadua, an activist of the pro-UNM Free Zone youth group, were being ‘persecuted’ by law enforcement for their Facebook pages.

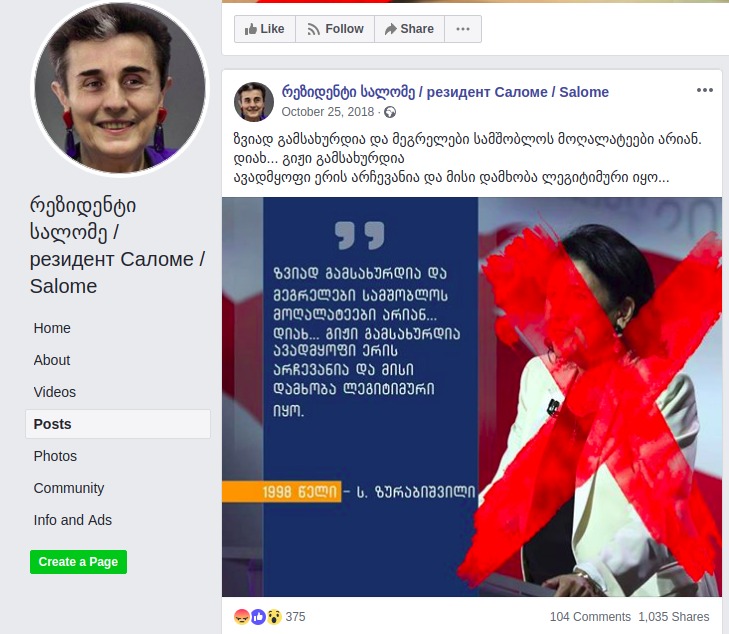

Saakashvili hailed Donadze for running the ‘Resident Salome’ page, and Chkadua for his popular Facebook page ‘Official Agency for Mocking the Kotsis’ (Kotsi is a pejorative term for members and supporters of Georgian Dream).

These pages targeted Zurabishvili with quotes falsely attributed to her.

Non-transparent financing and false news media

The anonymity of Facebook pages that use paid posts to engage in smear campaigns suggests a growing problem of undeclared money being used in election campaigns.

According to the same ISFED report cited above, 19 pages engaged in negative campaigns against presidential candidates pretended to be real news agencies. Ten of these appeared after the first round of the 2018 presidential elections.

While the official Facebook pages of candidates did not directly attack their rivals, the emergence of fake pages suggests this dirty work could have been outsourced to ‘independent’ and anonymous Facebook pages.

The problems do not stop with undeclared money and anonymity.

There were also at least eight Facebook pages that tried to misrepresent candidates’ positions by posing as their official pages or their supporters, such as ‘Unity of the supporters of the National Movement’, misrepresenting Vashadze’s camp, or ‘Salome Zurabishvili’, misleading voters about Zurabishvili’s positions.

The most notable piece of false information was the ‘discovery’ of Grigol Vashadze’s ID that suggested he was a Soviet KGB agent. There was also a fake story alleging that in 1998, Zurabishvili called Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the first Georgian president, and Mingrelians, an ethnic subgroup in Western Georgia, ‘traitors’.

Not all of the Facebook pages that engaged in political attacks in November produced and disseminated fake news. Some of the attack posts were satirical and only partisan in nature. But considering the large involvement of sponsored posts during the elections, watchdog groups like ISFED suspect that both Georgian Dream and UNM spent undeclared money to attack each other during the elections.

Fake news is here to stay

While most of the Facebook pages targeting presidential candidates became less active following the 29 November vote, by mid-January, specific pages that posed as news organisations on Facebook rose from 19 to 32.

Facebook pages like AllPress.ge, Newspaper.ge, and Fastnews.ge lie about the years they have been active; the domains included in their names are not used, and they cannot be reached through the phone numbers listed.

While social media channels of far-right groups do frequently spread ‘underreported’ (fake) reports on demographics and alleged crimes committed by immigrants, and some openly attack the Georgian Dream government on a number of issues (e.g. the anti-discrimination law, legalisation of marijuana, ‘selling’ residence permits to rich foreigners), the newer fake news agencies pose as more objective, regular, registered news organisations.

In March, after being elected president, Zurabishvili called the online slander and fake news ‘flooding social networks’ the new enemies of democracy.

But while Zurabishvili herself was targeted by a negative online campaign last year, the Georgian public has yet to see a clearer demand from the ruling party and their allies for a more transparent and effective investigation over organised and clearly financed campaigns waged against all critics of Georgian Dream.

Georgian Dream failed to respond to repeated requests for comment.