![Armenia’s ‘patronage democracy’ [Analysis]](/_next/image/?url=https%3A%2F%2Foc-media.org%2Fcontent%2Fimages%2Fwordpress%2F2019%2F12%2Felection-armenia-cropped.jpg&w=3840&q=90)

Armenia’s recent parliamentary election delivered a resounding victory to the incumbent Republican Party. However, behind the numbers lies a growing sense of discontent at a patron–client system that serves only certain elites.

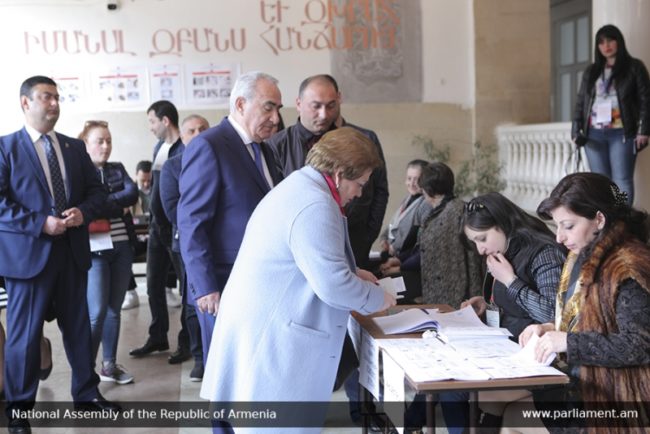

Armenia’s parliamentary election on 2 April was the election that changed everything, and yet seemed to change nothing at all. It was the first election held under a parliamentary, rather than presidential system, and the first major election held under a new constitution. And yet, the mood on the streets of Armenia was that of resignation and apathy; the results of the election no surprise to anyone.

The ruling Republican Party was the clear winner, winning 49% of votes. In distant second was the Tsarukyan Bloc, with 27%; in third, the newcomer Yelk (Exit) Bloc with 8%, led by Nikol Pashinyan’s Civic Contract Party; and in fourth, the Dashnaktsutyun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) with 7%.

Behind these numbers lies the complicated reality of a shifting political landscape in Armenia, one in which the dominant elements of the Republican Party have consolidated their political position within both the party and the state, while simultaneously disempowering and subordinating possible rival elites. This was accomplished by honing the Republican Party’s electoral techniques, which leverage the structures of patronage that the Republican Party has developed over an increasingly ineffective opposition.

Retrenchment in the Republican Party

Alexander Iskandaryan, Director of the Caucasus Institute, an independent Yerevan-based think tank, argues that since 2010, the Republican Party has engaged in a process of transformation and consolidation. According to Iskandaryan, in the 2000’s, the party gradually merged with oligarchs and Armenian economic elites to become a sort of countrywide trade-union for capitalists.

But, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the core of the Republican Party — a coterie of wealthy oligarchs and professional politicians — changed tack and began to consolidate their position, at the expense of their erstwhile allies. This process of consolidation began in 2010, with economic measures implemented by the Republican government under the auspices of preparing to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union, and continued with the electoral reforms that came into effect with the 2015 constitution.

Excluding business elites

These economic measures led to a partial de-monopolisation in the Armenian economy, reducing the personal financial resources that could be mobilised by the the now excluded business elites. This has made them more reliant on the party’s patronage, and weakened their positions versus the ostensibly more ‘loyal’ party apparatchiks.

Electoral reforms were a further attack on this once-dominant social stratum. By replacing a system which mixed proportional representation and single mandate constituencies with a system based entirely on proportional representation, they party has prevented regional bigwigs from converting capital into political power outside of a political party.

The emergence of the Tsarukyan Bloc is one result of this process. Representing the interests of powerful businessmen disempowered by the Republican Party’s core (particularly of its eponymous leader, oligarch Gagik Tsarukyan), it has emerged as the political voice of Armenia’s oligarchs and businessmen.

It should not, however, be seen as a true opposition in the strict sense of the term. Tsarukyan and his allies are still dependent on the benevolence of the Republican Party. Their businesses still function with a great degree of privilege (for instance with de facto tax exemptions) which the Republican Party can and has used as leverage when they step out of line. The future role of the Tsarukyan Bloc will thus likely be that of a junior coalition partner or ‘pocket opposition’, as the economic benefits of accepting this subordinate position far outweigh the costs of political disenfranchisement.

‘The will of the people’

The day after polls closed, the European Union praised Armenia’s election, with Federica Mogherini, the EU’s foreign policy chief, stating that despite reports of vote-buying and other irregularities, the election expressed ‘the overall will of the Armenian people’. This overly rosy assessment is undoubtedly coloured by the close ties that certain EU business interests have with the Republican Party, still, at a cursory glance, it looks like it might actually be correct.

Elections in Armenia have long been dogged by claims of fraud and manipulation. Vote-buying, ballot-stuffing, votes cast by deceased or non-eligible voters, and outright manipulation of the election results have been frequently documented over the years. Prior to this election, the EU made a €7 million investment to rectify some of these issues. Using this money, the Armenian government installed cameras in all polling stations, and bought electronic voter authentication devices — they also took further steps, such as publishing voter lists, and allowing independent observers to monitor the election process throughout the country.

As far as outright fraud was concerned, these measures worked. The electoral results matched the votes cast. Additionally, voter turnout, while not spectacular, was nonetheless impressive — over 60%, higher than the turnout in the last US presidential election.

And yet, popular discontent has been simmering in Armenia for years. Each summer, successively more disruptive protests erupt. In 2015, demonstrators staged the largest protest since Armenia’s independence, against a hike in electricity prices. In 2016, an armed group calling themselves the Sasna Tsrer (Daredevils of Sasun) stormed a police station in Yerevan’s Erebuni neighbourhood and called for a popular uprising against the government. Despite the violence of their actions (two police officers were killed in the ensuing stand-off), thousands of young people came out to the streets, even clashing with police in support of the group.

Patron–client democracy

How can this apparent contradiction be explained?

Vote-buying is part of the equation, after all, the exchange of cash for electoral support occurs outside of the view polling station cameras, and cannot be caught by voter-ID technology or voter lists. The deeper reason lies in the Republican Party’s almost total domination of Armenia’s state apparatus, which grants them both the vast financial resources needed for vote-buying and the institutional tools to pressure and otherwise extract votes from a sizeable portion of Armenia’s population.

The Armenian state, and by extension the Republican Party, serves as the employer for a large portion of the Armenian population. As a result, teachers, civil servants, and other government employees and their families are pressured into ‘returning the favour’ by voting for the ruling party. Additionally, the Republican Party’s utilises ‘gifts’, like the maintenance and construction of new infrastructure, such as roads or schools, or investment into agriculture, for example, purchasing tractors for a particular village.

In this, the Republican Party does not act as the representative of the Armenian people; it does not even pretend to enact their will. Rather, they are the patrons of the country and the public their clients. In return for patronage — a single cash payment, a steady wage, or a road — the Armenian people give them their votes.

‘Anti-corruption’ is not an ideology

The Republican Party’s success as a party of patronage has a great deal to do with the non-ideological nature of Armenian politics. Parties represent little more than their own interests, and elections are just the stage on which competition between different elites plays out. During election times, this manifests in the complete lack of substantive discourse.

All parties, including the Republican Party, come out publicly in support of such uncontroversial concepts as ‘growth’, ‘security’, and ‘anti-corruption’. When the parliamentary opposition criticises the government, it aims at individuals rather than the system — ‘the party in power is filled with corruption, our party however is not, elect us and Armenia will prosper’.

The Republic of Armenia is now over 25 years old, so it is to be expected that such a tired pitch falls on deaf ears. In an environment where no political party is trusted to serve the interests of the electorate, patronage wins by default. The greater the resources of a party to buy votes, institutionally pressure voters, and gift much needed infrastructure and amenities, the larger their share of the vote.

A new opening for genuine opposition

But, all this said, there is still room for an effective and popular opposition to emerge. The success of the Republican Party depends in large part on the apathy of Armenians. By establishing an electoral process which is in many ways more transparent than in the past, the government has given up much of the leeway they previously had to manipulate the results of an election once the ballots have been cast.

This provides an opening for a genuinely ideological party to come to power in future; a party whose promises and programme the Armenian people can really believe in. For that to occur, this party must go beyond the limited politics of personalities. It must have a concrete ideology that is not only attuned to the interests of the Armenian people, but is organically woven into their lives. Such a party is not likely to emerge from above, but much like the parties of the working class in late 19th century Western Europe, it will emerge from self-organisation by the Armenian public.

If the momentary explosions of Armenian protest movements can take on a less transient form, and transform into enduring structures of real popular will, then the chances are, even the formidable state apparatus of the Republican Party will not be able to stop them.