CRRC Georgia data found that individual political polarisation — how committedly partisan a person is — is relatively low in Georgia, despite concerns about the country’s polarisation as a whole.

Political polarisation is seen as a critical issue in Georgia, so much so that overcoming it is a condition for Georgia’s bid to secure candidate status in the European Union. Indeed, many argue that political polarisation is one of the main causes of Georgia’s democratic backsliding.

Past research has shown that political polarisation has not led to diverging views on policy or ideology in society. Rather, views seemingly only diverge on individual politicians and explicitly partisan events, like the Rose Revolution and major elections. .

Newly released research from CRRC Georgia suggests that at most three in ten Georgians can be categorised as affectively polarised, meaning that they distrust an opposing party regardless of their views on policy.

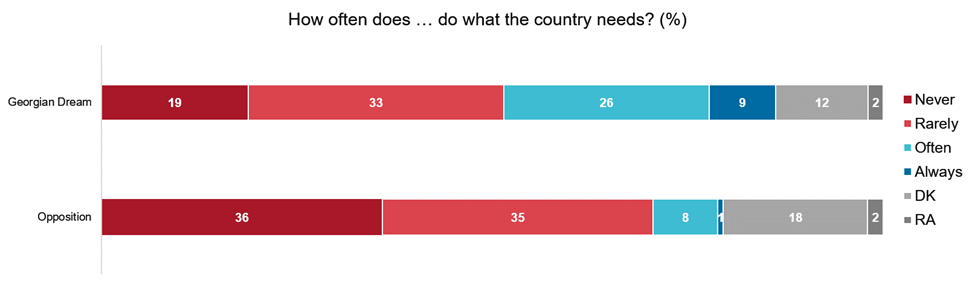

In the newly released study, respondents were asked how often they thought the ruling party and opposition did what the country needed.

Half of the electorate (52%) thought that the ruling Georgian Dream party rarely or never did what the country needed, while 35% reported that the ruling party often or always does what the country needs. As for the opposition, 71% of the public thinks that the opposition rarely or never does what the country needs, and only 9% of Georgians believe the opposition often or always does what the country needs.

To measure polarisation, the two questions were combined to construct a variable that measures whether an individual is politically polarised.

The logic behind the approach is that people who respond similarly to the two questions can be considered less polarised — they believe that both parties either work for the country or do not. In contrast, people who assess one of the two positively and the other negatively can be considered polarised.

This produces a scale ranging from zero to four, with zero meaning that the respondent was not polarised at all, reporting identical responses to the two questions, and four meaning that the respondent was very polarised, reporting a very positive attitude towards one party and a very negative attitude towards the other.

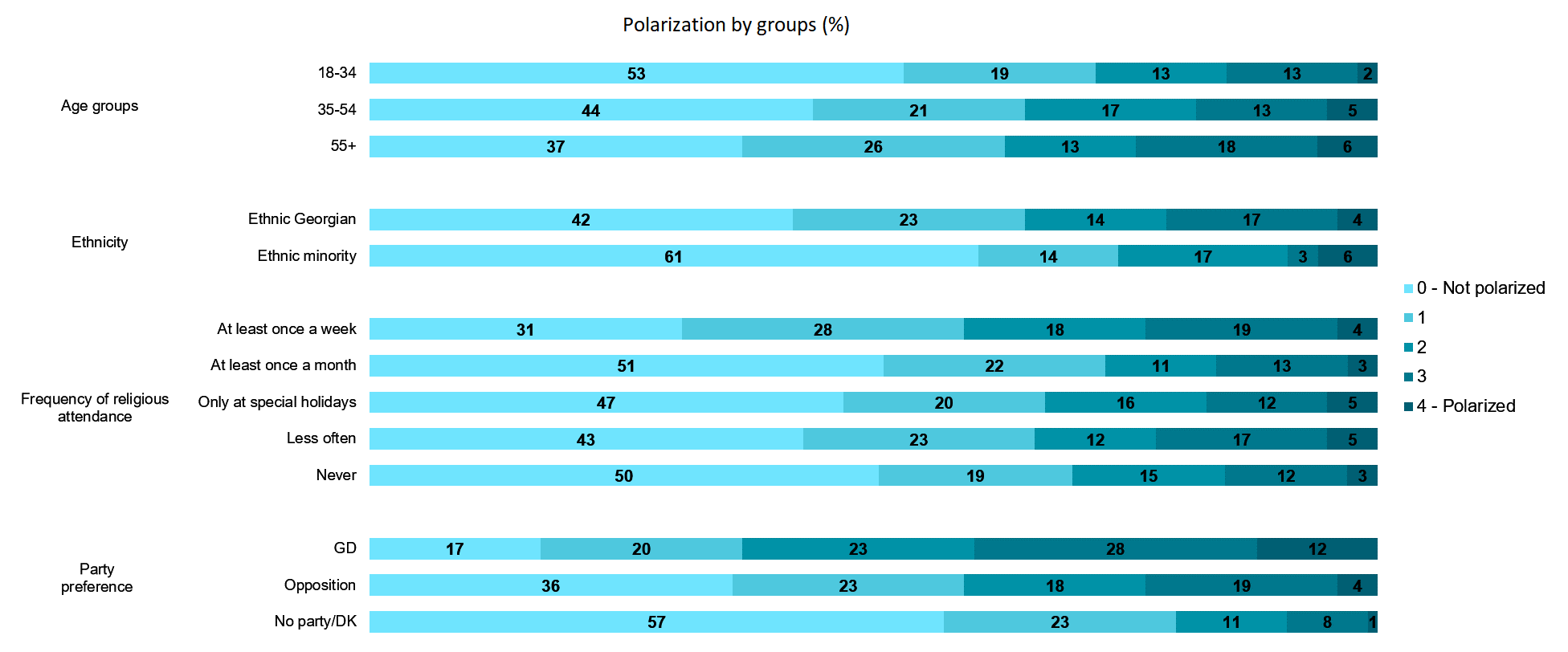

On this scale, almost half of the electorate (45%) was not polarised at all, while 4% was highly polarised. A further 15% was quite polarised, scoring 3 out of 4 on the scale.

A regression analysis suggests that someone’s polarisation is not associated with their sex, education, settlement type, employment status, or frequency of praying (a measure of religiosity).

On the other hand, respondent polarisation was related to age, ethnicity, frequency of religious attendance, and party preference. Older people, ethnic Georgians, people who attend religious services once a week, and partisans all tend to be more polarised than other individuals.

It is worth noting that the analysis used two different measures of religiosity because they behave differently with respect to polarisation.

People who attend religious services often tend to be more polarised than people who attend less frequently or do not attend religious services at all. However, when it comes to frequency of praying, people who pray often are not different from people who pray less often or never when it comes to polarisation.

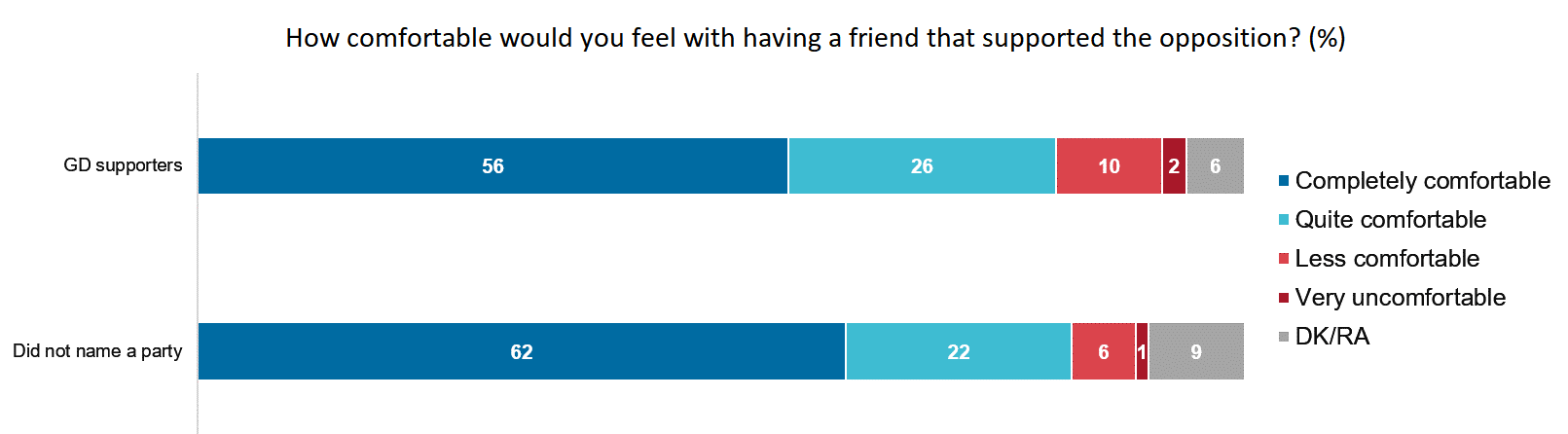

Measuring social distance among people with a party allegiance suggested that partisanship only has a moderate impact on friendships.

Georgian Dream supporters were more likely to say that they would feel uncomfortable with an opposition-leaning friend than voters who did not support any particular party. Similarly, opposition supporters were more likely to report that they would feel uncomfortable with a Georgian Dream-supporting friend than those with no party preference.

Regardless of these statistically significant differences, a very large majority of the public said that they would feel quite or completely comfortable with a friend with either political leaning.

While Georgian political discourse is often dominated by discussion of polarisation, the data suggests that a majority of Georgians are not polarised.

This article was written by Givi Siligadze, a researcher at CRRC Georgia. The views expressed within this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, the National Endowment for Democracy, or any related entity.