The social and political integration of ethnic minorities remains a challenge for the long-term democratic development of Georgia. But could ethnonationalist sentiments be hindering such integration?

Considering that one in seven Georgian citizens is of non-Georgian ethnic descent, ethnonationalism has the potential to estrange significant sections of society, presenting barriers to social cohesion and stability.

Although the failure to address this problem can be partially attributed to government and political institutions, the public’s attitudes and beliefs also likely serve as an impediment.

Data from the 2020 Future of Georgia survey suggest that about a third of the electorate exhibit some form of ethnonationalist sentiment.

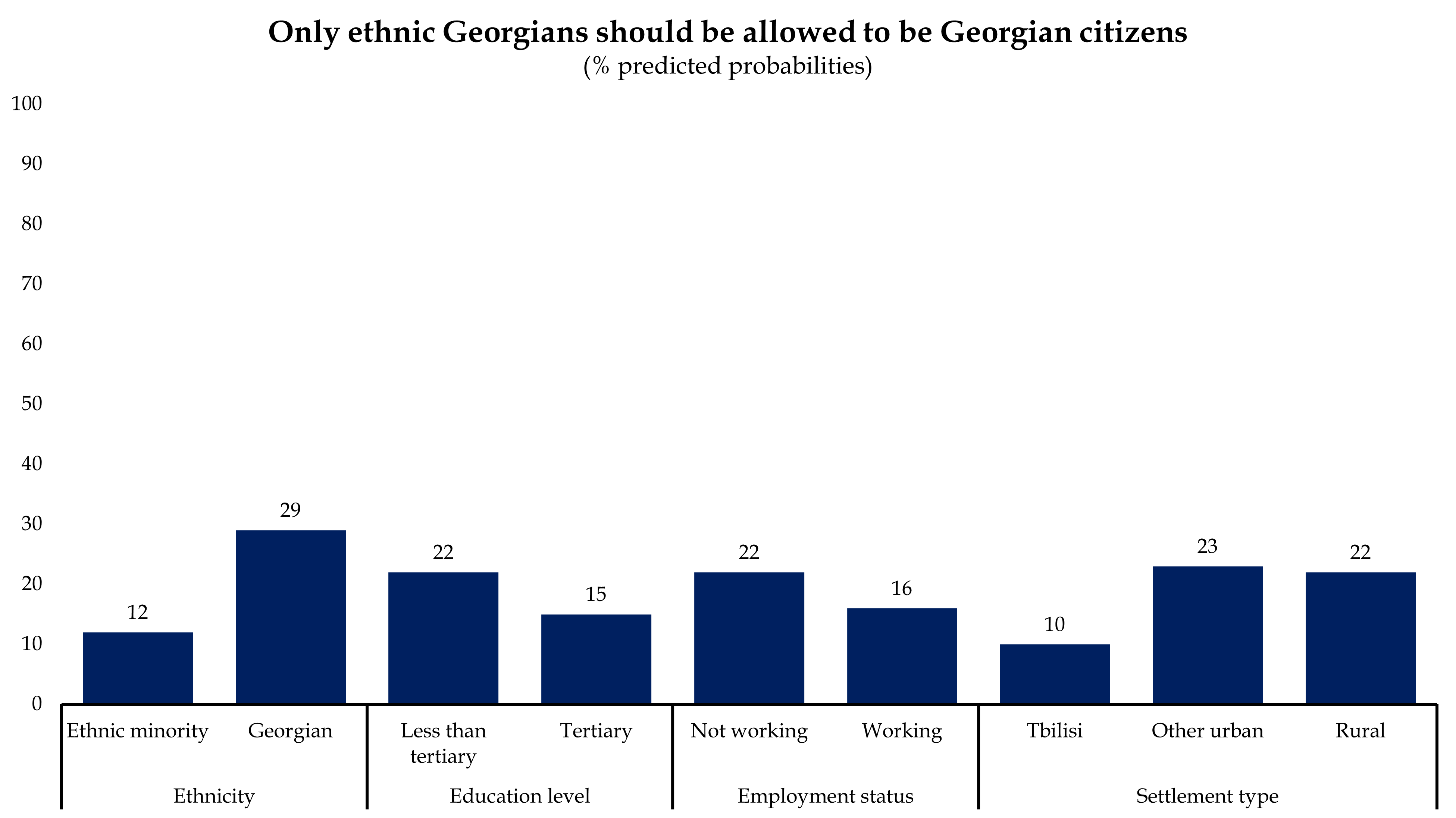

The survey found that around a third of the adult population (30%) think only ethnic Georgians should be allowed to be Georgian citizens, while around two-thirds disagree (61%).

A regression analysis suggests that some groups are more prone to equate nationality with ethnicity than the others.

Ethnic Georgians, people with lower levels of formal education, people without jobs, and those living outside of Tbilisi were found to be significantly more likely to report that only ethnic Georgians should be allowed to be Georgian citizens compared to ethnic minorities, people with tertiary education, employed people, and residents of Tbilisi.

Other socio-demographic variables, including age, sex, and IDP status were not associated with the above statement.

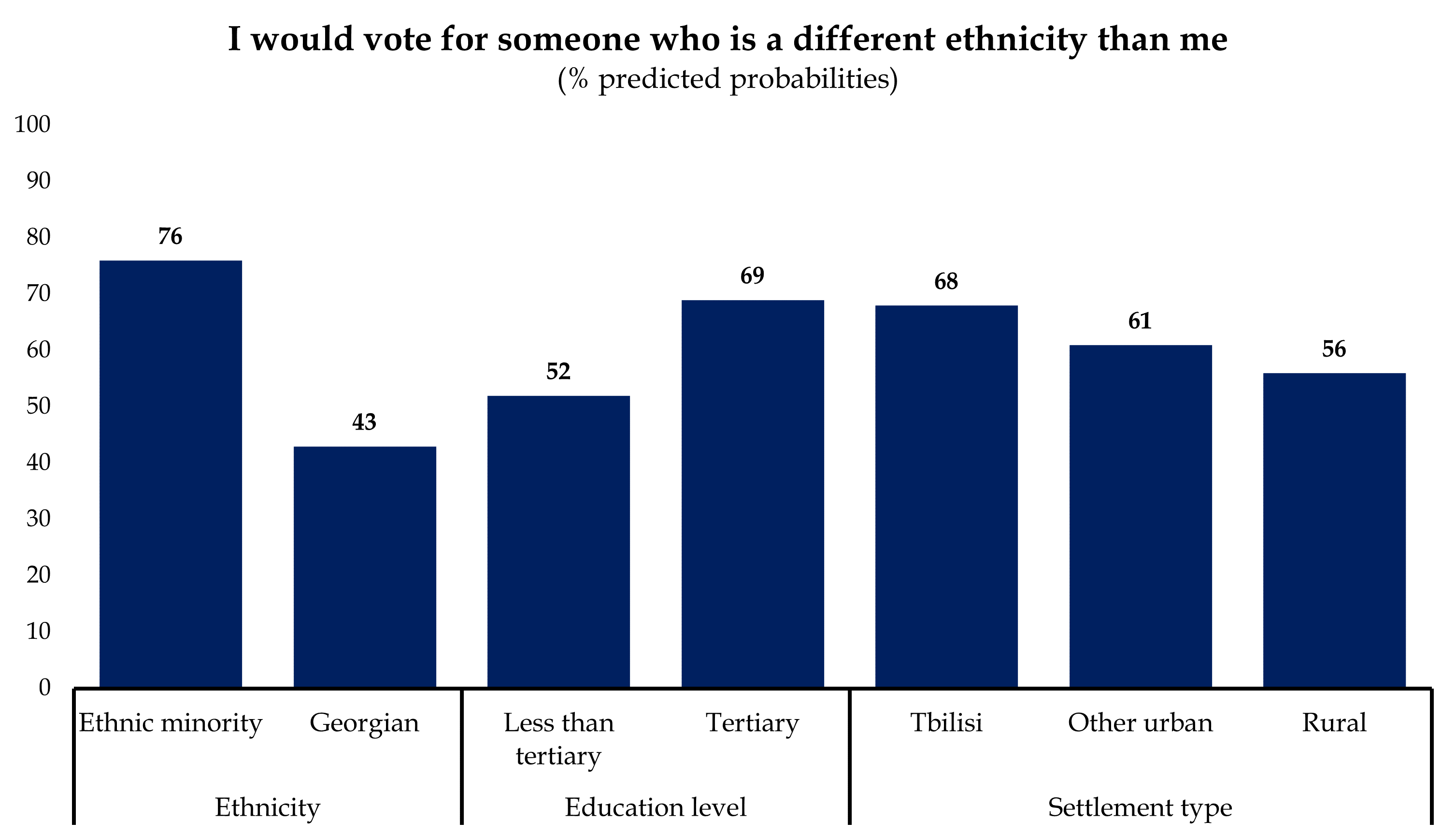

Respondents were also asked whether they would vote for someone of another ethnic group, with 46% reporting they would.

A regression model examining who would vote for someone of different ethnic descent suggests a similar pattern.

Ethnicity, formal education level, and settlement type appear to be associated with readiness to vote for someone of a different ethnicity than themselves.

Ethnic minorities were 33 percentage points more likely to report that they would vote for someone of a different ethnicity than themselves.

People with a higher education, residents of Tbilisi, and poorer individuals were also more willing to vote for someone who is a different ethnicity than people with lower levels of education and people living outside of the capital.

Willingness to vote for someone of a different ethnicity was not associated with other socio-demographic variables, including age, sex, employment situation, or IDP status.

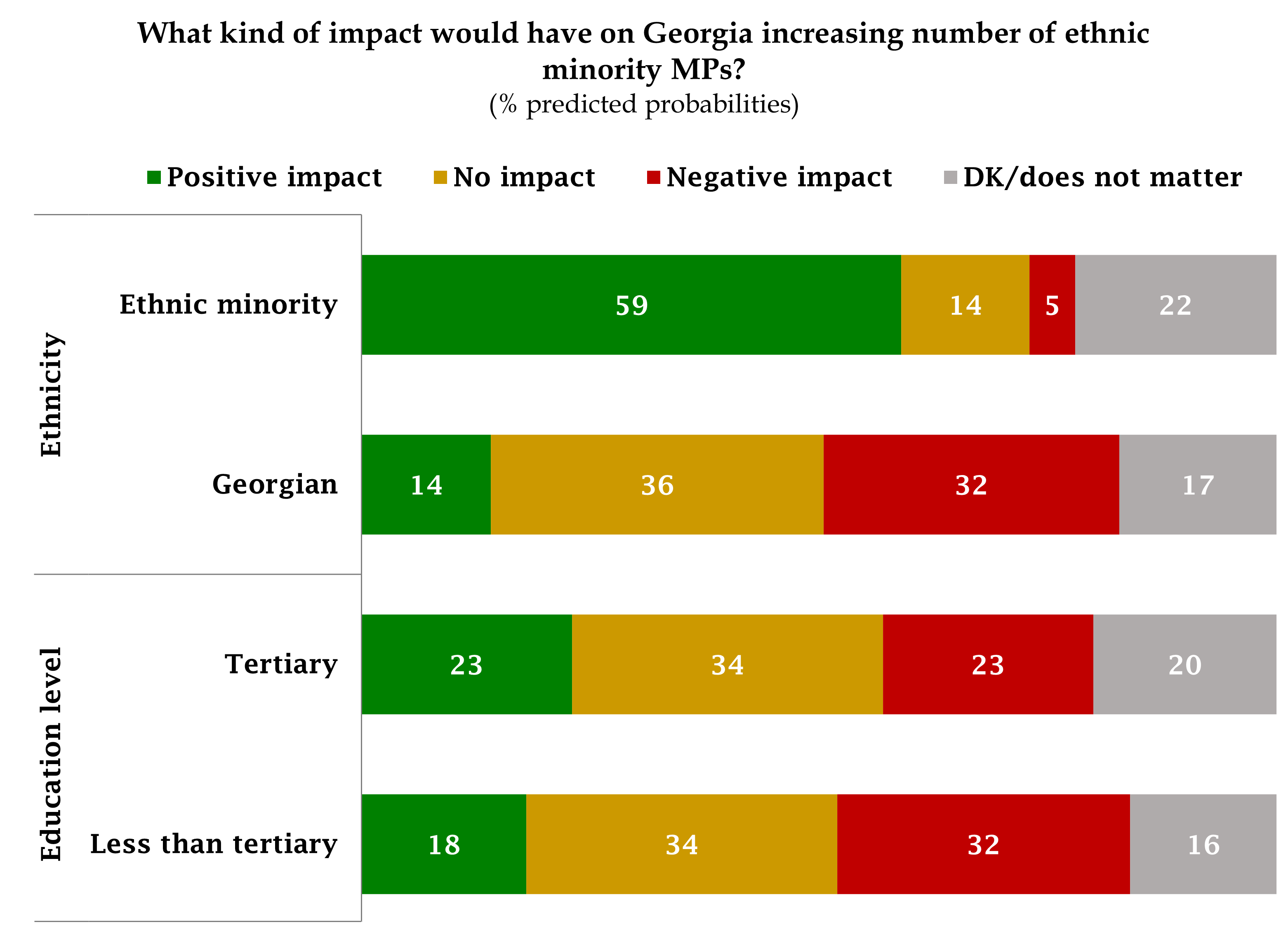

In terms of the perceived impact of the increased political presence of ethnic minorities in parliament, ethnic Georgians and people with lower education levels seem to differ from ethnic minorities and people with tertiary education.

More specifically, ethnic minorities were found to be four times more likely than ethnic Georgians to report that an increasing number of ethnic minority MPs would have a positive impact on Georgia.

Controlling for other factors, ethnic Georgians have a 14% chance of saying that having more ethnic minority MPs would have a positive impact on the country compared with a 32% chance of saying the impact would be negative.

People with tertiary education were more likely to see a positive impact of more ethnic minorities in the legislature and less likely to see a negative impact than people with less years of formal education.

Even though the majority of the adult population of Georgia do not seem to harbour explicitly ethnonationalist sentiments, a substantial section of the public do say that Georgian citizenship should be equated with Georgian ethnicity, that they would not vote for someone with a different ethnic background, and that increased presence of ethnic minorities in Parliament would negatively affect Georgia.

Considering that approximately every seventh Georgian citizen is not an ethnic Georgian, these ethnonationalist and ethnocentric sentiments pose a serious challenge to the long-term democratisation and state-building prospects of the country.

Furthermore, some groups tend to exhibit ethnonationalist sentiments more than others.

People with lower levels of formal education and people living outside of Tbilisi were less favourably inclined towards increased participation of ethnic minorities in politics compared to those with a higher education and residents of the capital.

Note: The above data analysis is based on logistic and multinomial regression models which included the following variables: age group (18-35, 35-55, 55+), sex (male or female), education (completed secondary/lower or incomplete higher education/higher), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), wealth (an additive index of ownership of 10 different items, a proxy variable), employment situation (working or not), IDP status (forced to move due to conflicts since 1989 or not) and ethnicity (ethnic Georgian or ethnic minority).

The data used in this analysis is available here. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.