Explainer | After a month of simmering protests, Georgia erupted: why now?

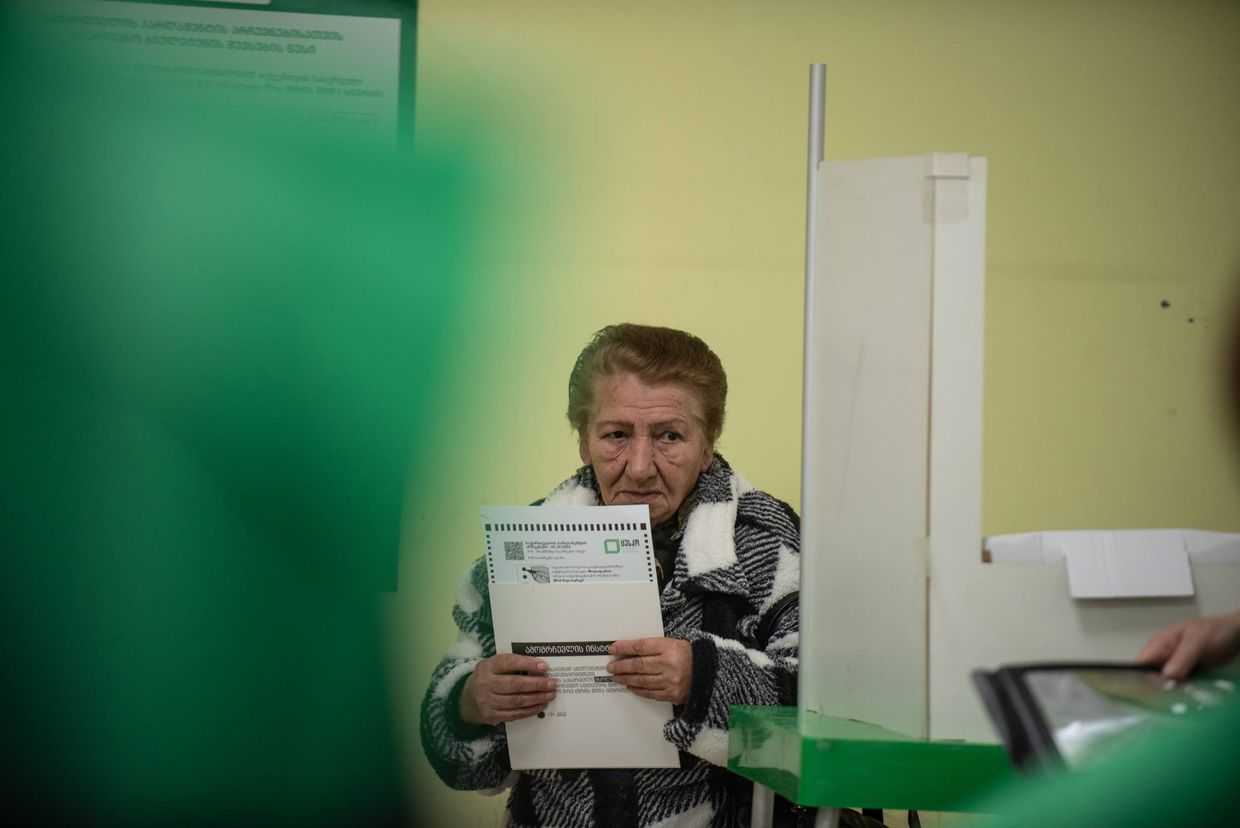

At a moment when it appeared as if demonstrations against electoral fraud and democratic backsliding had fallen into a feeling of bitter acceptance, protests in Georgia exploded suddenly on 28 November after Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced the government was suspending its bid for EU accession until 2028. But why did the government choose to take such an unpopular move? And why was this the trigger for such mass discontent?

In Tbilisi and other cities and towns across the country, the mood — and the stakes — feel fundamentally different than in the past year of political turmoil.

The EU U-turn seems to have struck a deep nerve across the spectrum of Georgian society, as it goes against perhaps the most commonly held position in the country.

The pledge to seek Euro-Atlantic integration is both enshrined in the constitution and supported, at least rhetorically, by Georgian Dream and the opposition alike.

According to various polls conducted in recent years, public support for joining the EU has hovered somewhere in the high 70s to more than 80%.

Despite disagreements over approaches and tactics, Georgia’s EU accession has remained a consistent through line spanning from Mikheil Saakashvili’s tenure to the current day.

‘Throughout [Georgian Dream’s] rule in Georgia there has been an unspoken contract between the government and the people – Georgia’s pro-Western stance is a non-negotiable and anyone who crosses that red line will commit political suicide’, says Maia Otarashvili, Director of the Eurasia program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Until Thursday’s announcement, Georgian Dream has repeatedly emphasised accession is one of the party’s main priorities. Moreover, it used this pledge as an ostensible cover to obfuscate its shift away from the West. ‘Georgian Dream got away with mocking and bullying the Western partners and even feuding with the government of embattled Ukraine, as long as formally it was actively involved in EU accession talks and guaranteeing the safety of Georgia’s visa-free EU travel deal’, Otarashvili tells OC Media.

Even the U-turn itself was accompanied by a doubling-down on the promise for Georgia to join the EU by 2030. As the immediate backlash mounted, Kobakhidze and other Georgian Dream officials claimed the about face did not mean the party has abandoned the EU, but rather that it would give the country more time to properly enact reforms and enter the bloc with ‘dignity’.

Kobakhidze’s haphazard explanations did little to convince the public that the government still intended to follow through on its constitutionally-defined promise.

Why the EU U-turn was so controversial

The current political crisis in Georgia has different starting points depending on one’s perspective, but the most commonly accepted trigger was the initial introduction of the foreign agents law in the spring of 2023, which sparked large-scale protests and the eventual scrapping of the law. It was then brought back a year later, with the government steamrolling the legislation through parliament despite a repeat of the previous year’s protests.

While the protests over the law accumulated hundreds of thousands of participants, it did not lead to the type of government defections happening currently.

Similarly, protests against electoral fraud led to mass gatherings in Tbilisi, but not in other cities, and without the type of vitriolic response the EU U-turn has caused.

According to Eto Buziashvili, a researcher at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, Georgia’s ‘EU bid was different — it touched on a core aspiration that unites Georgians’.

‘For many, the mission and dream of joining the EU is deeply tied to their national identity and future. The denial of this goal marked a breaking point for public frustration,’ Buziashvili tells OC Media.

While society was prepared for some level of electoral irregularities, ‘the sheer audacity and scale of [Georgian Dream’s] manipulation caused widespread shock’, and when coupled with the seeming failure of the opposition to effectively respond to the fraud, it led to ‘a sense of helplessness and a growing nihilism among the public’, Buziashvili says.

There was a feeling that Georgian Dream so effectively planned the electoral fraud that revealing the truth would be ‘nearly impossible’, Buziashvili tells OC Media, which ‘may explain the absence of a massive and sustained wave of protests right after the elections’.

The EU U-turn was ‘the final straw in a series of actions by [Georgian Dream] that had infuriated the public’ and inflamed the simmering anger below the surface.

As Otarashvili explained, Georgian Dream ‘crossed the red line it had previously dared not cross’.

Georgians are now ‘demonstrating that they are willing to fight for a European future, because without it they feel they have nothing left to lose’, she tells OC Media.

At a time when protests were waning, Georgian Dream decides to poke the bear

From the perspective of Georgian Dream, the decision to come out and openly declare the halting of EU accession seems perplexing.

Protests against the election had already begun to wane, with several key dates, such as the official certification of the vote and the inauguration of the new parliament, passing with diminished protest turnout.

Opposition leaders and President Salome Zourabichvili had announced a boycott of the new parliament and declared it to be illegitimate, but there was no clearly defined plan to push back against the government official means. Parliament was convened without a single opposition member present in what was characterised as a violation of the constitution. Georgian Dream appeared to be untroubled by the opposition backlash and international condemnation of the election, and determined to push forward, illustrated by the selection of the controversial lawmaker Mikheil Kavelashvili to be the next president.

But just as Georgian Dream appeared to have consolidated its rule, the EU U-turn announcement reignited the protests, which immediately grew into a movement surpassing what had been seen throughout 2024.

In practice, the EU U-turn had already happened many months, or even years earlier, as the government revived the controversial foreign agents law despite explicit statements from EU officials saying it would halt Georgia’s path toward accession.

Following its passage in spring, the EU said Georgia’s accession had been effectively frozen.

Nonetheless, Georgian Dream continued to say it would seek to join the bloc while taking few actual steps to do so.

As a result, it is unclear why Kobakhidze decided to openly state the obvious instead of continuing on the same path of promises with no action.

Analysts who spoke to OC Media concurred that the EU U-turn appears to have been a miscalculation on the part of Georgian Dream; a hasty decision based on a variety of factors.

Otarashvili says it likely ‘has to do with the short-sightedness of the increasingly authoritarian and egotistical [Georgian Dream] leadership’. The party wanted to make it ‘look like the Georgian government was breaking up with the EU, not the other way around. The decision was made to soothe [Georgian Dream] leadership’s ego, not as a serious strategic move’.

Nonetheless, given Ivanishvili’s personalistic control of the party, the true motivations behind the decision are likely known only by a small circle of confidants.

Possible Russian influence, a desire to avoid the heightened scrutiny that accompanies EU candidate countries, or simply counting on holiday-weariness to blunt the protest movement, are all potential explanations that should not be ruled out, analysts told OC Media.