Medical authorities and community groups in Georgia are cooperating in their endeavour to prepare the public, and first and foremost, the most at-risk groups, for yet another epidemic. Experts say that if managed right, monkeypox should be easier to contain than COVID-19; this, however, would take early preparations and proper messaging.

Around 40 days ago, following the first major outbreak outside the African continent, the Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, declared monkeypox a ‘global health emergency of international concern’.

The virus is currently largely affecting gay and bisexual men, transgender women, and also men who engage in homosexual contact but who self-identify as heterosexuals.

Despite reasonable fears that overfocusing on queer men or the larger group of men having sex with men (MSM) may stigmatise the community further, there is a growing consensus that sunlight is the best disinfectant against hate and prejudice, which are exasperated by health disinformation.

‘It is paramount that the groups of society that are currently most at risk of infection are aware of monkeypox’, Vasily Esenamanov, Hub Coordinator for the Southern Caucasus at the WHO Health Emergencies Programme told OC Media.

Esenamanov underlined that ‘any person, whether an MSM or not, can get monkeypox’.

An open conversation about monkeypox and the groups it affects the most at this stage could also mitigate the risk that governments end up dragging their feet in taking timely preventive measures.

In Georgia, social and political homophobia may indeed be another hazard to public health efforts, and local healthcare authorities seem aware of this challenge.

It would likely take a coordinated effort by medical authorities, top political decision-makers, and community leaders to strike a balance in public messaging and also to secure at least some vaccines to spare Georgia from a large outbreak.

Meet the new guy in town

On 15 June, Georgia’s National Centre for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC) joined other countries in reporting the first monkeypox case, only to inform the public soon after that they had tested their rapid response system just fine.

Monkeypox, or MPXV, is a new genetic relative of the well-known smallpox virus, which the globe had eradicated by the 1980s due to a successful transnational campaign for mass vaccination.

According to the NCDC, patient zero in Georgia, who had recently travelled to Europe, was isolated, tested, and discharged from hospital shortly after. They also closely watched their recent contacts for typical symptoms.

The NCDC told OC Media that they did not see an elevated risk of a monkeypox outbreak, but warned that this would ultimately come down to ‘the intensity of its transmission globally and a possible change of its transmissibility rate as a result of a possible mutation of the virus’.

Most people recover from monkeypox within a few weeks without needing any treatment or a vaccine, but its symptoms are anything but nice.

While they may typically start with fever and swollen lymph nodes, skin rashes escalating to lesions seem to be the worst recurring memory among recently recovered patients; they occur not only on the face but often also on the genitals and anus, and usually cause strong discomfort and pain.

Managing suspected and presumed cases

In May, the Georgian healthcare authorities devised a Monkeypox Outbreak Response Plan, a set of tentative guidelines to prevent and manage monkeypox cases, including a contact tracking protocol.

The plan identified ‘pregnant women, children, immunocompromised individuals, men having sex with other men (MSM), travellers, and medical personnel’ as high-risk groups and stated that formulating a Risk Communication and Community Engagement strategy and action plan was their next goal.

According to the guidelines, Georgian medical workers would treat any unexplained acute rash that is combined with either a headache, high fever, inflamed lymph nodes, muscle aches, joint stiffness, back pain, or abnormal physical weakness as a suspected monkeypox case.

Where a patient had had multiple anonymous sexual encounters or a history of travel to countries where monkeypox is endemic 21 days before symptoms emerged, they would be considered a ‘presumed’ monkeypox case.

Georgian medical authorities seem to be treating airborne contamination as unlikely, as the official Georgian protocol advises that someone who has ‘low-risk contact’ with an infected or possibly infected person should go on with their daily routine. The only requirement would be to stay in the same geographical area in order to be monitored.

Those who may have come in contact with potentially contaminated objects would be treated as ‘medium-risk contacts’, and they would be instructed to keep away from children under 11, pregnant women, and heavily immunosuppressed people.

Those directly exposed to a monkeypox patient would be ‘recommended’ to undergo a 21-day quarantine, closely monitored for seven days. Where skin or respiratory symptoms are present, a person will be told to stay away from other household members, including pets, ‘as far as possible’.

While the guidelines set out criteria for discharging a monkeypox patient from hospital, they remain vague if hospitalisation would be compulsory for isolation.

In cases of hospitalisation of unconfirmed but possible monkeypox cases, the NCDC instructed health services to isolate the patient in a separate room with a separate bathroom, with limited access to other sections of the premises and moving only with a protective face mask and with any lesions covered.

The NCDC would consider medical caretakers and lab staff as a high-risk category eligible for vaccination within four days of direct possible exposure, ‘if available’.

Anti-queer sentiments: a monkeypox ally

Until now, Georgia’s NCDC has tiptoed around the issue of the most at-risk groups for monkeypox, while the Health Ministry entirely refused to comment on the issue citing their wish ‘not to alarm the public’.

In late August, the NCDC became more forthcoming, and confirmed to OC Media that they considered MSM as a group of concern.

‘Globally, the outbreak primarily disadvantages men who have sex with other men. However, any person exposed to a virus is at risk of being infected, regardless of sexual orientation’, the NCDC underlined in a 29 August statement to OC Media.

The pool of those most at risk includes those with multiple sexual encounters regardless of sexual orientation, men on PrEP (pills that prevent contracting HIV), and sex workers, who rely on having multiple sexual encounters as a source of income.

Vasily Esenamanov from the WHO told OC Media that it was not yet known if monkeypox could be spread through sexual transmission routes, like semen or vaginal fluids.

‘But direct skin-to-skin contact with lesions during sexual activities can certainly spread the virus’, he added.

‘Stigma and discrimination in Georgian society is certainly a recognised issue, which can hamper access to diagnostics and treatment’.

That the current outbreak globally is centred among MSM can be explained by closed and highly active networks and sexual culture: the demographic group statistically has more multiple or anonymous intimate contacts.

At the crossroad between health disinformation and hate

The risks that misunderstanding monkeypox may lead to even higher levels of anti-queer stigma in Georgia seem real, especially considering that anti-queer hate groups dominated the anti-vaxxer movement in Georgia that actively spread healthcare disinformation.

In late July, Tina Topuria, a self-described medical worker who misinformed the public on the COVID-19 pandemic through her TV show on channel Tavisupali Arkhi (‘free channel’), resurfaced again to allege that person-to-person transmission of monkeypox was possible only through same-sex contact.

‘The vulnerable group is also being identified. The same WHO Director said, the same head of the WHO’s European Division said it before, and ours [sic] also say the same — that this is a disease of a specific group… The common population is not at risk’, Topuria incorrectly claimed.

‘The risk group, as they say, and I’m citing, are men who came in sexual contact with men […] so the transmitters and those vulnerable to it are this group’, she continued.

In fact, monkeypox poses a danger to the population at large, and the stigma attached to male-to-male sexual contact may only help the virus, as it can instil a false sense of safety among others.

‘There is still a widespread perception that only men who have sex with men are at risk of monkeypox, which is certainly not true’, the WHO’s Vasily Esenamanov said.

‘While currently monkeypox is mainly spread among MSM communities, in principle it is not limited to this group of the population. Monkeypox transmission occurs through close physical contact with respiratory secretions, skin lesions of an infected person, or recently contaminated objects such as bedsheets, for example’.

In their 29 August response to OC Media, the NCDC gave a strong-worded message against stigma, highlighting how it can complicate healthcare efforts.

‘We should remember that access to medical service is a fundamental right while stigma and discrimination lower rates of referrals to medical institutions leading to delayed confirmations of cases and hence, to adequate medical care; In terms of healthcare, they also hinder the effective management of an epidemic outbreak’.

Working with the community

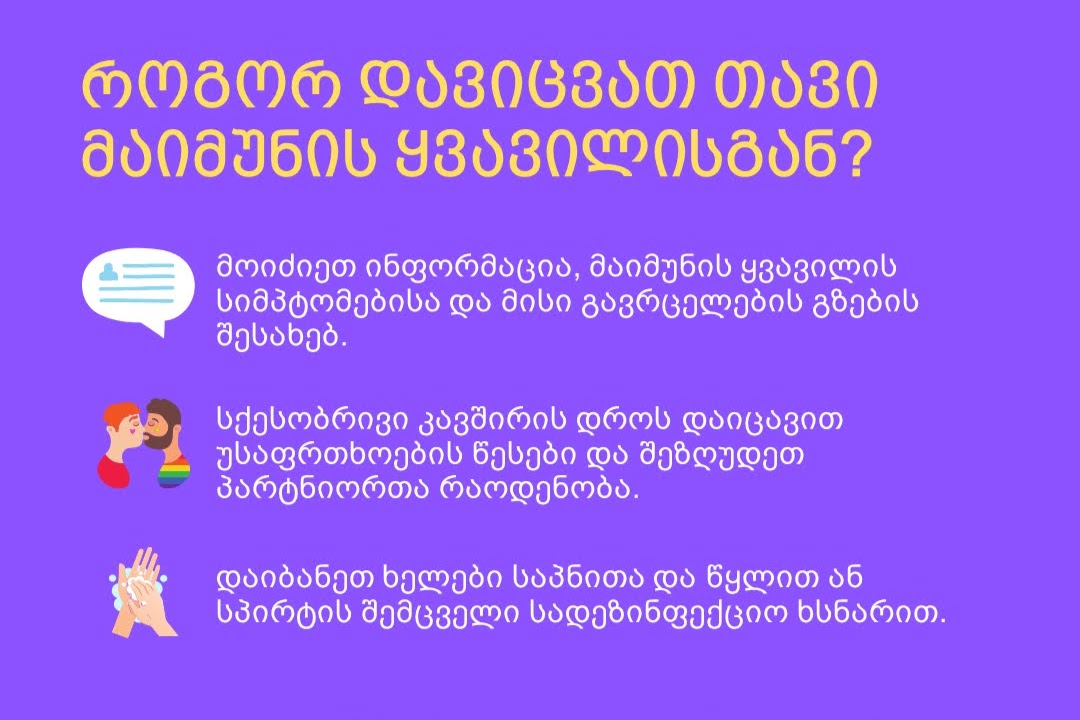

In May and July, the NCDC provided the Equality Movement and Tanadgoma, two community-based service providers, with a set of recommendations on the prevention of monkeypox to disseminate further.

Giorgi Khobua, HIV/AIDS programme manager at queer rights advocacy group the Equality Movement, confirmed to OC Media that the NCDC reached out to his organisation first with an appeal to ‘actively work’ on this issue.

Khobua noted that the appeal strongly urged them ‘not to enhance stigma’ in any material they came up with.

For the NCDC, like the WHO, avoiding ‘risky sexual behaviour’ by limiting multiple sexual contacts is their best advice apart from vaccination.

The NCDC told OC Media that in any case, ‘retaining contact information of partners so that if it is needed, contacting them is possible’ was crucial.

The Equality Movement said they were considering toning down some of the advice on having fewer sexual partners to avoid ‘sex-negativity’.

‘If one does not feel safe or just wants to act relatively more careful, we expect an adult to arrive at such a personal decision independently’, the Equality Movement’s Giorgi Khobua told OC Media.

He added that otherwise, they planned to follow the healthcare recommendations they were given and convey messages underscoring hygiene and keeping contact details of partners.

Improved trust and safe channels

Stigma, prejudice, expectations of being judged and shamed by medical workers, and a wish to prioritise privacy and confidentiality over health safety even if a doctor is queer-friendly may be strong factors pushing queer people in Georgia to avoid healthcare providers.

Earlier this year, the Georgian Public Defender’s Office reported that ‘even when members of the LBGT+ community had no negative experiences with medical personnel, they frequently avoided visiting the doctor, except in cases of absolute necessity’.

A 2020 study by Tanadgoma commissioned by the UN Population Fund highlighted that limited resources for testing for sexually transmitted diseases and confidentiality breaches were also more acute in rural areas.

While the situation for queer people in the wider medical sector remains dire, advocacy groups like the Equality Movement, Tanadgoma, and the Harm Reduction Network, have a track record of providing key healthcare products and services to queer people.

This is often done entirely anonymously, including online.

OC Media learnt from community centres that brochures about monkeypox would soon be added to ‘Kiki boxes’, available to order for free through the selftest.ge platform. The boxes have so far included self-test kits for HIV/AIDS, sexual health items, and brochures on sexually transmitted infections and diseases.

Sexual health advocates have also prioritised cooperation with Georgia’s Infectious Diseases, AIDS, and Clinical Immunology Research Centre, commonly referred to as the AIDS Center.

‘Speaking from my experience in case management, beneficiaries, including trans women who most frequently experience discrimination, actually love them’, the Equality Movement’s Giorgi Khobua told OC Media.

According to Khobua, community members have found accessing PrEP pills through community centres where ‘peer educators’ offer risk assessment before providing them or forwarding their cases to trusted medical workers far more comfortable.

Any hope for monkeypox vaccines for Georgians?

Beka Gabadadze, a Georgian queer community organiser and social worker at Tanadgoma, told OC Media that he was not as much concerned about queer men’s hesitancy to refer to healthcare providers as about the lack of preventive mechanisms currently at hand.

‘I see a problem in that we don’t have anything for prevention, including vaccines that are already available in other countries… I’m under the impression that it’s not even planned’.

Currently, there’s a race among many economically developed countries like the US, Australia, and the UK to secure stockpiles of Jynneos (also known as Imvanex or Imvamune), a smallpox vaccine that is effective against monkeypox.

At present, the WHO does not recommend mass vaccination against monkeypox, but there is an increasing demand for it for target groups.

At the early stage of a potential monkeypox outbreak, Georgia seems to be partially relying on the legacy of a late-Soviet era smallpox vaccination campaign. Both the WHO and Georgian health authorities regard this as largely effective against monkeypox.

Georgia’s NCDC confirmed to OC Media that they had recommended the Health Ministry acquire monkeypox vaccines.

The NCDC said they were also closely following an emerging global ramp-up in vaccine production.

Recently, users of Grindr, a popular queer dating app, started seeing an online survey form on their mobile screens. The questionnaire idea originally came from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, translated by the NCDC into Georgian.

The survey includes questions about possible inoculation against monkeypox, indicating that the availability of smallpox vaccines, the best case scenario, could additionally be connected to the propensity of target groups who would actually use them.

This is to be expected amidst a global vaccine shortage, inequality of access, and Georgia’s poor record of using the coronavirus vaccines they received through the international vaccine-sharing mechanism, COVAX.

For the Equality Movement’s Giorgi Khobua, it is a promising sign that Georgia procuring the monkeypox vaccines was not a hopeless prospect.