Georgia’s Anti-Corruption Bureau has demanded that five prominent civil society organisations hand over extensive financial records and information about their beneficiaries, including data about domestic abuse victims.

The groups that received requests for information from the bureau were the Civil Society Foundation, women’s rights group Safari, Transparency International — Georgia (TI), the Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC), and the Future Academy, which implements educational youth projects.

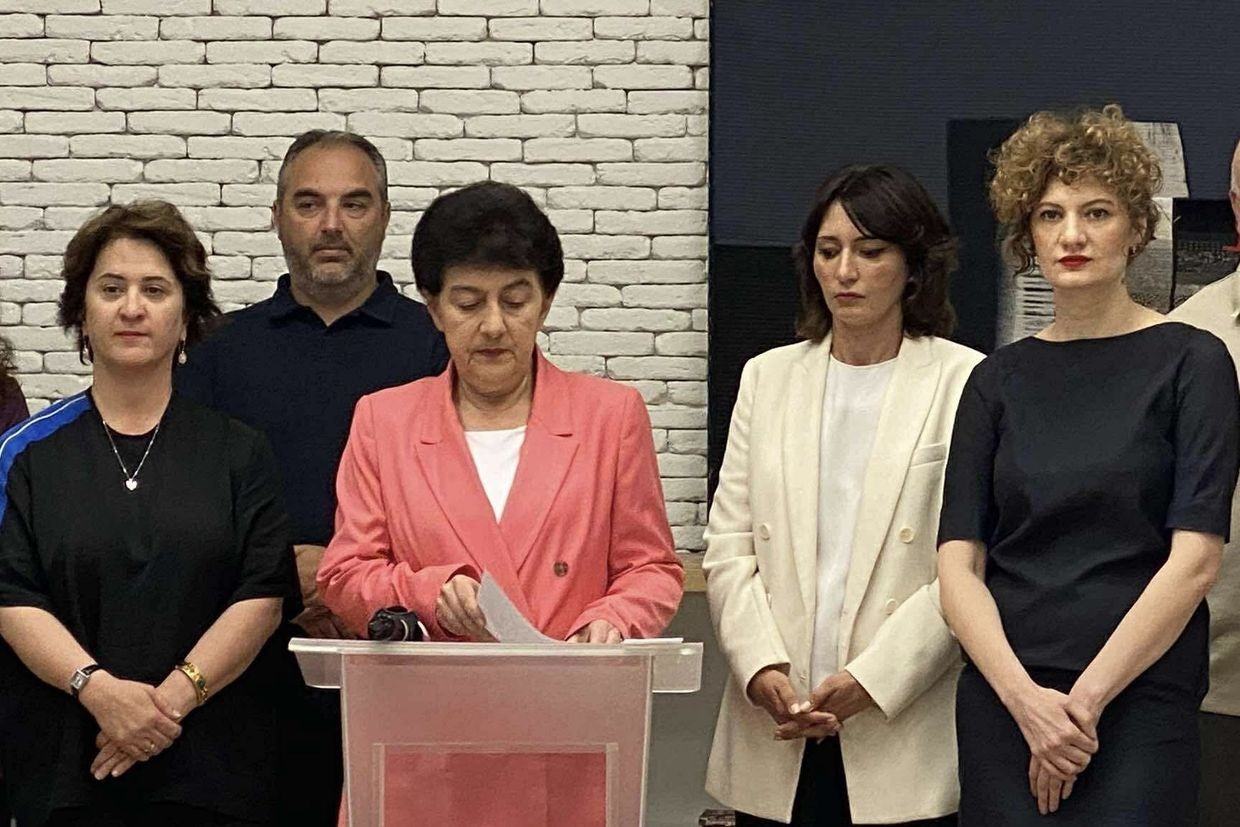

The organisations have announced they will not comply with the bureau’s request.

In a joint press briefing on Wednesday, the groups stated that the government had now begun enforcing legislation targeting civil society — laws that critics have dubbed the ‘Russian laws’, comparing them to the draconian regulations enacted by the Kremlin.

The organisations received an order from the Tbilisi City Court, which granted the Anti-Corruption Bureau’s request for the data.

According to the groups, personal information has been requested about their beneficiaries, encompassing a wide range of categories, including victims of torture, female survivors of violence, teachers, journalists, unlawfully dismissed public servants, and their family members.

‘[They have requested] the personal ID numbers, names, surnames, photographs, financial and banking information, as well as health data of everyone who trusted us and benefited from our assistance’, said Keti Khutsishvili, the executive director of the Civil Society Foundation.

In their statement, the organisations declared that they do not intend to ‘betray the trust’ of their beneficiaries — even if it leads to their prosecution or imprisonment.

‘Once again, we declare that we will not live under Russian laws, we will not accept the sabotage of Georgia’s European future, and we will continue to fight for the rights of the Georgian people’, the statement read, emphasising that the government’s goal was the destruction of a free civil society.

The five groups did not specify which laws the Anti-Corruption Bureau used as a legal basis to request the information. However, OC Media understands that the agency used three laws: the law on political associations of citizens, the law on combating corruption, and a provision in the law on grants that was recently approved by Georgian Dream.

According to the court orders seen by OC Media, the request covered the period from 1 January 2024 to 10 June 2025, and demanded information not only about the organisations’ beneficiaries, but also large volumes of other kinds of data.

The requested data ranged from the organisations’ bank transactions to grant agreements and contracts signed in cooperation with international charitable, humanitarian, or other public organisations, financial institutions, foreign governments, and both legal and natural persons registered either abroad or in Georgia.

The bureau has also requested detailed information about work plans related to the agreements and contracts, disbursement schedules, and comprehensive project budgets. It also sought information on activities carried out under these agreements — including details about beneficiaries. According to the order, all of this must be accompanied by photo and video documentation of the activities implemented under the agreements and contracts.

The order demanded interim and final financial reports on payments made within the scope of the contracts, as well as ‘records of correspondence and related written communication, in cases where agreements exist in the form of correspondence between the parties’.

Later, the head of the bureau, Razhden Kuprashvili, responded to the organisations, accusing them of ‘deliberately spreading false information’ and denying that the bureau was requesting personal data without legitimate grounds.

‘The legal and financial documentation we have requested does not go beyond the boundaries of the law and is aimed solely at examining the purpose of the activities of organisations that receive grants or engage in political activity’, he said, adding that ‘the confidentiality of both professional and personal data will be fully ensured’.

Kuprashvili also said the bureau’s work would focus on identifying organisations whose activities do not align with their declared objectives and are ‘covertly engaged in political activity’.

In recent months, the ruling Georgian Dream party has adopted a series of restrictive laws and amendments, several of which have specifically targeted civil society organisations and independent media.

One of the amendments made to the law on grants in April required civil society organisations to obtain ‘the consent of the government or an authorised person/body designated by the government’ before receiving a grant from outside of Georgia. In addition, donor organisations must also submit a copy of the grant to the Georgian government beforehand.

During the same period, the ruling party introduced what it called a word-for-word translation of the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). Under the law, a foreign agent is defined as any person who is under the control of, or acts at the direction of, a foreign power and acts in the interests of that foreign power.

The enforcement of both laws — including decisions about who is ‘acting at the direction of a foreign power’ and who is receiving unauthorised grants — has been entrusted to the Anti-Corruption Bureau: the agency that requested beneficiary data from the five organisations.

Georgian Dream has repeatedly claimed that the new bills are necessary to fight the ‘influence of external powers’. Nonetheless, critics of the ruling party have insisted that these changes aim to undermine the media and civil society in an already fragile democracy.

The restrictive laws are being passed in a parliament where opposition is virtually nonexistent. Following the disputed 2024 elections, opposition parties refused to participate in parliamentary sessions.

Since then, the ruling party has been initiating and passing several new restrictive pieces of legislation without any obstacles, targeting media, civil society, and other critics.