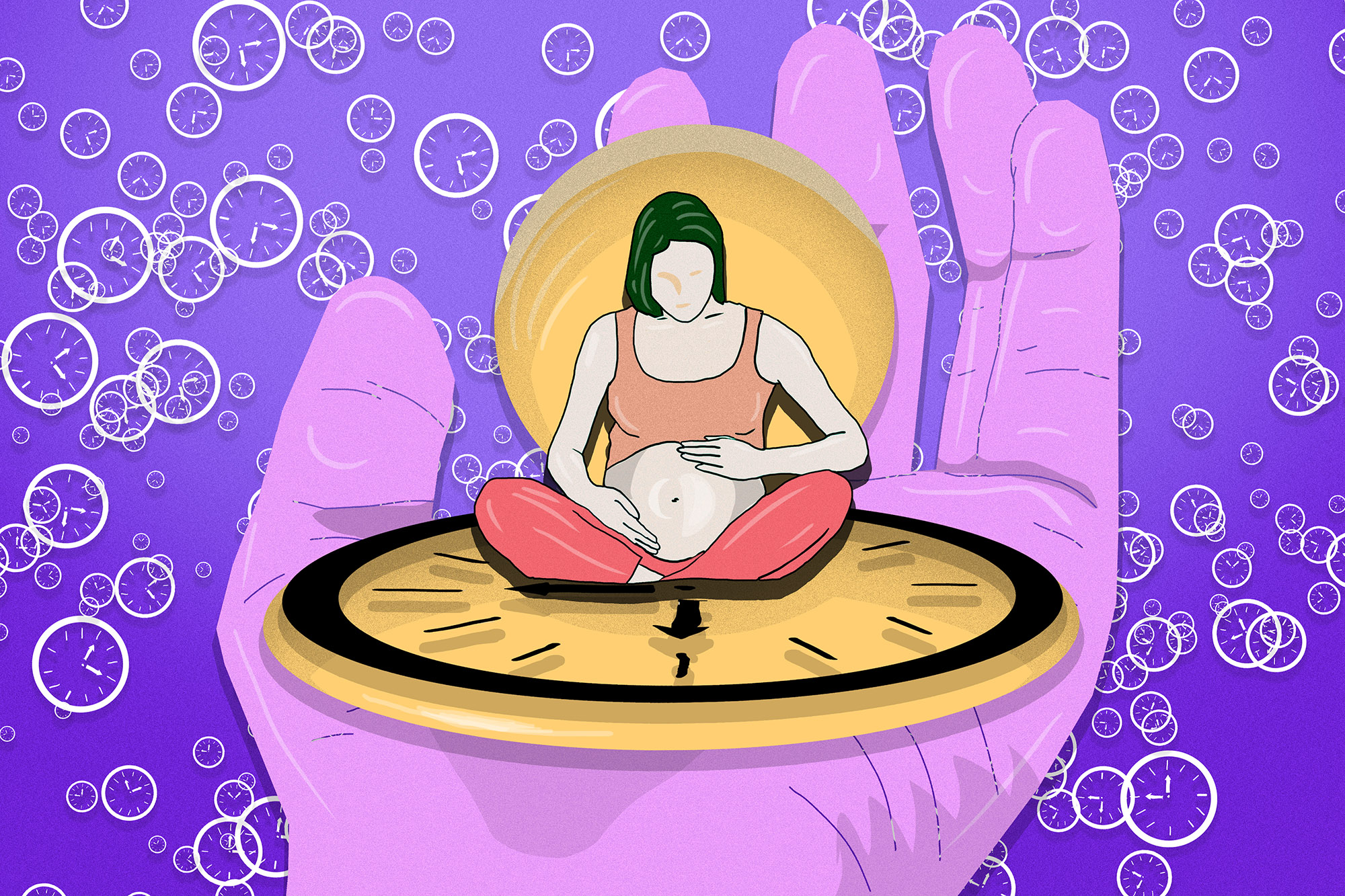

For some in Armenia, surrogacy represents a chance at happiness for an infertile couple. But for the women who become surrogates, the experience can be challenging.

Gayane (not her real name) is a 30-year-old woman from Armenia’s southeastern Vayots Dzor Province. Gayane says she divides her life into two parts: that of ‘ordinary Gayane’ and ‘surrogate mother Gayane’.

‘I got married at the age of 20; I was a happy woman’, she tells OC Media. ‘At 21, I was already a mum and I was sure I’d have two more kids, that we’d be a big, happy family and live carefreely but…’

Gayane’s dreams faded within a year. The family fell into financial trouble and in order to put food on the table, Gayane’s husband left to work abroad.

‘He worked abroad for a year; we lived quite well during that time but we missed him a lot. He came back a year later, stayed a month, and then left again. He was working in construction. Then an accident happened; he acquired a disability and couldn’t do any physical work.’

[Read on OC Media: The manless villages of Lake Sevan]

In the hope of finding a job, Gayane says she applied to different employment agencies, bought newspapers, followed the news.

‘I started looking for a job and realised that I could make a lot of money by providing great benefits for others.’

‘I had an acquaintance who had not had children for many years: one day I saw her with a child in her arms walking in the yard. I was very glad and congratulated her, and she told me that she had her baby with the help of a surrogate mother.’

‘She was talking about how much she had paid, which gave me an idea. I began to study the topic. Half a year later I was already a surrogate mother. Half a year after that, the second phase of my life began’.

Surrogacy: the last hope of motherhood

Surrogacy is a procedure whereby a woman agrees to carry a pregnancy for another person or people who will become the newborn child’s parent(s) after birth.

In their 10 years of marriage, Lilit and Sedrak (not their real names) have knocked on the doors of dozens of doctors in their attempts to have children.

‘Hundreds of times we took various tests. We tried artificial insemination twice and nothing came of it. For the first five years, we weren’t so worried about it, but after that, the real panic began’, Lilit tells OC Media.

She says that every visit to the doctor cost them a large sum of money. They spent roughly ֏150,000–֏200,000 ($300–$400) on tests alone. A similar sum was spent on various drugs. The couple paid about $4,000 for artificial insemination.

‘We collected the money with great difficulty, I was working at a school at the time. My salary was about $150 [per month]. My husband was working at several places at the same time. After the second failed attempt [at artificial insemination] we realised that we didn’t have any money left and decided to try to adopt a baby.’

But here too, the family was met with failure. They wanted to adopt a newborn baby, but they told OC Media that they were informed that not a single newborn was up for adoption in Armenia at the time. Without children, Lilit was ready to give up on her marriage.

‘I had decided to seek a divorce when one of my friends advised me to seek the help of a surrogate mother. I had a long discussion with my husband about the issue, we chose a clinic, made some financial adjustments, and began collecting money.’

‘It took us two years to psychologically prepare ourselves and to collect the required sum.’

Lilit and Sedrak paid around $20,000 for the service. This included both legal services and payment to the surrogate mother — Gayane. Gayane did not wish to disclose how much of that sum was apportioned to her.

At the clinic, the couple was introduced to Gayane, who was to be their child’s surrogate mother.

The responsibilities of a surrogate

The Surrogate Motherhood Institute, like all surrogacy institutions in Armenia, is regulated by the 2002 Law on Human Reproductive Health and Reproductive Rights.

The law places a number of rules and restrictions on potential surrogate mothers. A woman must be aged 18–35, she must undergo medical and genetic testing to ensure she is healthy. A surrogate mother cannot also be an egg donor. A married woman can only be a surrogate if her husband consents. Finally, the same woman can become a surrogate mother only twice.

‘We rented a separate apartment for Gayane, as we had jointly decided that she would live separately during the pregnancy and be closer to us in Yerevan’, Sedrak says. ‘For the whole 9 months, Gayane was our focus. We provided her with everything she needed — quality food, clothes, and other essentials.’

‘Now we thank God we met Gayane at the clinic and thanks to her, we have felt the pleasure of becoming parents.’

He says that when they decided to seek the help of a surrogate mother, they were given another option: instead of using the candidate offered by the clinic, to find a woman themselves.

‘In this case, we could save money. But it was also risky and difficult to find a woman in accordance with the law.’

According to the law, the relationships between surrogates and those paying for their services are governed by written agreements.

A surrogate mother is obliged to have a medical registration in the early period of pregnancy (before 12 weeks), constantly be under a doctor’s supervision, strictly follow their recommendations, and to take care of her health.

If she lives separately, the surrogate mother must keep the person or spouses using her services informed about the pregnancy.

‘I felt his first moves’

Zara Hovhannisyan, a human rights activist from the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Women, says that the topic of surrogacy remains taboo in Armenia.

She says that parents do not want their child to know they were born with the help of a surrogate mother, while surrogates themselves often feel ashamed of resorting to the procedure to make money.

The process can also be psychologically challenging for a surrogate.

‘Serious psychological work is done with a surrogate mother from the very first moment’, psychologist Araks Karapetyan tells OC Media.

‘It is very important from the outset to prepare a woman psychologically for the idea that though she is bearing the foetus, it is not her child. Although physiological alterations during pregnancy can cause psychological problems for the surrogate mother.’

‘Yes, she may not be psychologically ready to hand over the baby, but the problem here is regulated by law’, Karapetyan says.

The law states that a surrogate mother has no parental rights to, and no responsibility for the child once they are born; she cannot refuse to hand them over.

Hovhannisyan recalls a case several years ago in which an 18-year-old surrogate unsuccessfully tried to refuse to hand over a baby she had carried to term to its biological parents. She says that after this, the government introduced rules in which only women who have already given birth to a biological child of their own can become surrogates.

Gayane, who has not seen the baby she carried since he was born, admits that she herself had trouble dealing with letting go.

‘I carried the baby inside me, I felt his first moves’, she says. ‘It was hard for me. I don’t think I’ll become a surrogate mother for the second time.’