Along the Armenian–Azerbaijani border, ceasefire violations occur frequently from both sides. In the villages of Gazakh and Tovuz districts of Azerbaijan closest to the frontline, some report the shooting has become less frequent, but the violence can still mean a loss of livelihood or even a loss of life.

Jumshud Mursalov, 53, was born in Bala Jafarli; there are currently six members of his family still living in the village.

Lying near the border with Armenia in Azerbaijan’s north-western Gazakh District, the village frequently comes under fire from over the border, and it faces a lack of irrigation water.

‘We have to live here, we have nowhere else to go’, Mursalov tells OC Media. ‘When the roof of our house was full of holes, the executive head of Gazakh came to our village and ordered the replacement of our house’s slate. But the roof got holes again, as the shooting continued. We are not afraid in the daylight, but the darkness has become a nightmare and we call sleeping a “small death” ’.

There used to be a railway line going through Bala Jafarli that connected western Azerbaijan to Baku. When war broke out, the railroad stopped operating; only the electric power poles and disassembled railway tracks remain.

In the nearby village of Jafarli, local residents have similar complaints. Though most of the population raise livestock, there are few pastures available. What’s worse, when the war began, water flowing from Armenia through a pipe system stopped, and a drought began. An artesian well has since been built to provide water for both drinking and irrigation.

The village also comes under fire — in 2015, a shell landed in the yard of local resident Ahad Asgarov, damaging his car. A few remnants of the shell are clearly visible in his bedroom wall.

‘In 1992, a missile fell on my dad’s house, completely collapsing it’, Asgarov tells OC Media. ‘At the same time, another missile fell on the back house, which my father built for us. It also collapsed.’

‘For a year, we lived in a secondary school in Gazakh. Then we settled down in the old kindergarten opposite our destroyed house. We are three brothers; we grew up, we worked. In 2008, we dismantled the old kindergarten and built our own home’, Asgarov says.

The Aghstafachay Water Reservoir was completed in 1969. Residents of the village of Chakhmakli, which was flooded in order to form it, were transferred to Jafarli. The reservoir now provides irrigation water to several districts in north-western Azerbaijan.

The reservoir is fed by the River Aghstafachay (Aghstev in Armenian), which originates deep in Armenia.

The Ministry of Natural Resources of Azerbaijan has repeatedly claimed that the river is polluted from the Armenian side. From winter to spring, the dam is full, but in summer and autumn, when the water levels drop, household waste featuring Armenian text is left behind.

Sadiga Jafarova, 60, has been living in the village of Kamarli, to the north of Jafarli, for the past 12 years. She says that for over a year, there have been no sounds of gunfire in the village.

[Read from the village of Barekamavan, 4 kilometres from Kamarli on the Armenian side of the border: No friendship in Armenia’s ‘village of friendship’]

‘Before, the situation was unbearable; our home was repeatedly fired at’, Jafarova tells OC Media. ‘During the shooting, we would hide in the corner of the house. After the situation reached a certain point, we rebuilt the ceiling of the house using concrete.’

Jafarova currently lives at her older brother-in-law’s house. In 1993 and 1995, he got lost while working with his sheep and was captured. The first time, he spent six months in captivity. He passed away in 2007.

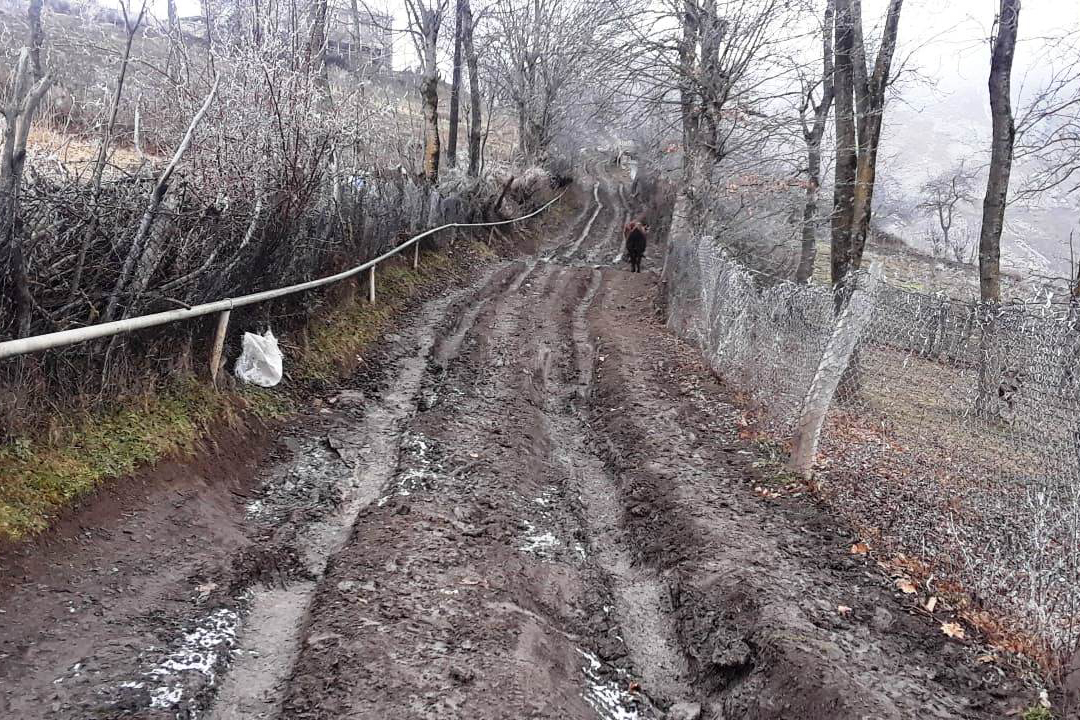

Munjuglu, in the Tovuz District also lies close to the Armenian border, nestled in the mountains. No one wants to live in the areas of the village closest to the frontline, leaving only 19 of the village’s 30 houses occupied. Local resident and farmer Ilgar Musayev says the reason most of the population has emigrated is mainly the lack of a real road.

‘The road from the [bottom of the valley] to the village is just three kilometres. but we cannot use it when it rains, due to the mud, or during winter, due to the snow. A special vehicle is needed to get to the district centre.’

‘Whenever someone falls ill, or even when women are pregnant, we get them out of the village a long time in advance. If we had a road, people would stay here and there could even be opportunities for tourism’, Musayev says.

‘Though we have no real fear of Armenian soldiers, there are problems when grazing animals, because Armenian soldiers will open fire on the grazing lands if they see people.’

Because the population make use of dryland farming techniques, there is no problem with irrigation water, though drinking water is still an issue.

‘Three to five neighbours came together and built a two-kilometre water line, carrying water from 200 metres away with wagons’, Musayev said.

The village of Aghdam, in Tovuz District, is another settlement close to the frontline. Mathematics teacher Zamig Askerov, 32, has lived and worked in Agdham for nine years.

‘For the last year, it has been calm. It was very difficult before. The shootings continue, but it’s not as intense as before. In the village, there are homes that have collapsed after being hit by a missile. Five of them have recently been repaired. The school I work at is also guarded by a retaining wall.’

Askerov adds that the villagers have suffered a lot from the war; there were civilian casualties. There are also residents that are ‘disabled and who have bullet fragments in their body’, he says.

According to Askerov, the population is mainly engaged in raising cattle and producing grain. Some fields, however, are too close to the battlefield, meaning the grain cannot be harvested.

‘Another problem is fires on the Armenian side. During autumn, when the grass is yellow, they burn areas. If the fire is not extinguished on time, people’s lives and property are in danger.’

This article is published as part of International Alert’s work on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which is part of the European Partnership for the Peaceful Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (EPNK), a European Union Initiative. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media, International Alert or its donors.

This article is published as part of International Alert’s work on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which is part of the European Partnership for the Peaceful Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (EPNK), a European Union Initiative. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media, International Alert or its donors.