Georgia’s textile industry is plagued by low salaries and rife with labour abuses. In this multi-part series, OC Media went inside the factories for a first-hand account. In part I, we look at how employees are organising and how the unions work (or don’t) at the Kutex and Imeri factories in Kutaisi.

‘Who has been told, “If you don’t like it, go home?” ’ the union organiser asks.

All the women raise their hands.

Later they add that they have heard harsher things too — ‘Fuck off’ or, ‘I’ll come over and drag you by the hair’ are just some of the things they report being told by their superiors.

On 15 July, in front of the Kutex textile factory in Kutaisi, nearly all of the factory’s 120 workers have gathered as part of a one-day protest to express discontent over the multitude of offences they have been subjected to from the factory’s management: late salaries, humiliation, an unclear management structure, and cut working hours.

Kutex, which began operations in 2016, used to produce jeans for Turkish retailer LC Waikiki from the day it was opened. In July 2019 the factory’s acting director Giorgi Gogolashvili told RFE/RL that the company revoked the contract after the last stock of product was turned in with many flaws.

OC Media reached out to LC Waikiki for comment. The company refused to go into detail about the revocation of the contract, stating simply: ‘LC Waikiki does not have a commercial or organic relation with the company [Kutex]’.

The factory’s owner, Mehmet Kurt, a Turkish citizen, is expected to come to the negotiations, and more importantly, to give out the salaries that were due five days ago.

Today is Monday — ‘bank day’ — when many of those with loans are supposed to pay.

Workers directly confronting the director is uncommon in Georgian factories. The director is usually an unapproachable authority, who at one and the same time has almost total control over the fate of their workers but rarely ever comes into contact with them.

In the case of Kutex, the separation is enforced not only by company structure but also by language, with the Turkish-speaking director surrounded by a coterie of bilingual managers who ensure that workers do not have direct access to the top of the company’s hierarchy.

Finding a voice

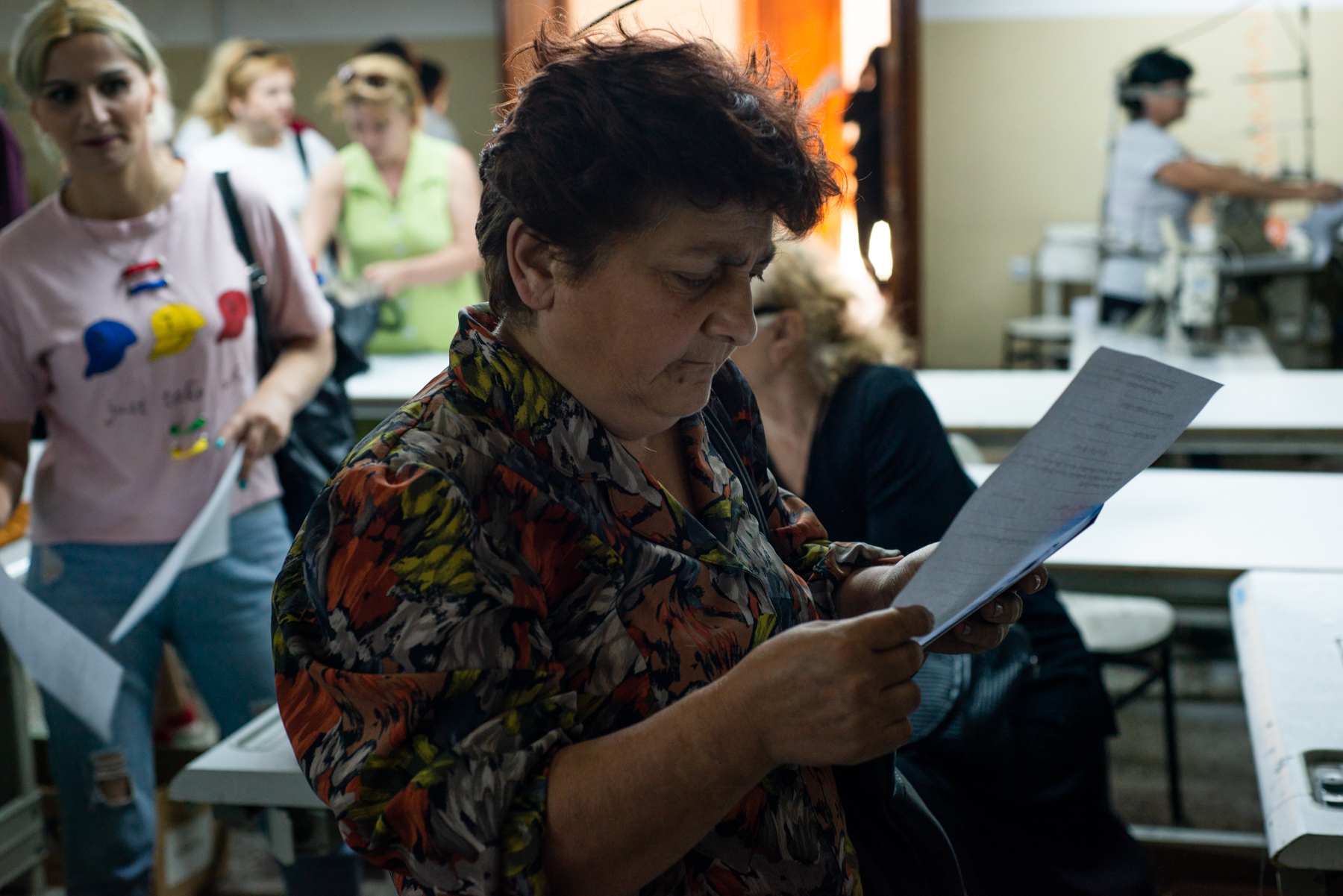

The women anxiously discuss all the wrongs that have been done to them at the factory with Irakli Mkheidze, director of the Kutaisi Trade Union, and Giorgi Diasamidze, who chairs the Agriculture, Light Industry, Nutrition Industry and Manufacturing Industry Workers’ Union. This is the first time they’ve done so openly. Before they banded together, the company’s heavy-handed response to any hint of worker dissent ensured an atmosphere of repressive silence.

‘It seems like everyone is our boss here’, one woman said. ‘The director, the quality controllers, the regular administration workers — everyone has the right to come and yell at us. They’re overstepping their authority, but it doesn’t matter to anyone. The situation is very tense and unhealthy. They think they stand above the workers and have the right to humiliate us.’

‘There is an inhuman attitude here’, another worker chimes in. ‘Starting from the director and ending with the foreman. We sometimes resist, but they find the most vulnerable worker to attack.’

The women recall one tailor who left an extra thread on a pair of jeans and the technologist threw them in her face — she started crying from the pain and humiliation.

‘I don’t need to be yelled at, I am a human being, just explain what I’ve done wrong’, another says. ‘The other day, the new model [of jeans] came in and I was so scared of making a mistake that I just stood up and said — I cannot sew this.’

‘The owner demands a certain quantity. But our contract is based on hours, quantity has nothing to do with it — yet people still believe him’, another woman says. ‘This man has studied our psychology and acts accordingly. He wants us to feel worthless because we “haven’t learned how to work” in two years.’

Despite the accumulation of grievances, it was the late salaries that finally united everyone.

Diasamidze came to Kutaisi from Tbilisi in the hopes of forming a new union in Kutex. In an industry where staff turnover is high, it’s a rare opportunity — there are currently only two unions in Georgia’s textile industry.

The spark

Tea Tsnobiladze, a tailor at Kutex, was the first to begin organising. The weekend before the protest, she collected 90 signatures from employees, alongside a collective list of grievances. The petition was meant for union organisers, to show them that the workers were ready to unite. But, more than that, it was also meant to show her fellow workers that their struggles were not theirs alone — to break them out of their solitude.

‘I started working [at Kutex] without prior experience’, Tsnobiladze told OC Media. ‘For a year, everything was fine. When the problems began and I started talking, people sat scared and silent. I always pointed out what I didn’t like. People saw that what I was saying was what was in their hearts and minds. You just need to give them a single impulse.’

Ultimately, Tsnobiladze was moved to action not by her own experience with the company, but what she saw happening to the women around her.

‘When I witnessed my coworkers being humiliated, I couldn’t stand this — I could never stand such things even from childhood. I always get in trouble because of others. I should have been a human rights advocate, probably.’

To organise and express discontent in Georgia is considered almost uncouth — with unemployment levels high (officially 13% but with surveys putting it as high as 21%) workers feel indebted to the factory for providing them with the opportunity of a job, even if it means up to 10 hours of work each day, for a mere ₾300 ($100) per month.

When problems arise, workers usually try to adapt to the conditions or they simply leave. ‘The staff turnover in the textile sector is high and that makes it vulnerable — like the hospitality sector or construction’, union head Giorgi Diasamidze says. ‘For employers, these people are just machines.’

When there’s no material to work on, tailors were dismissed and would have to remain idle until new orders arrived. They would not be paid during this period, even though their contract remained in force — a violation of Georgia’s Labour Code.

‘Mehmet [Kurt] blames us for it. He says we’re producing flawed stock which he can’t sell and therefore can’t get new orders. These “flaws” are something he manipulates us with. Sewing is a kind of a craft where it’s impossible to go without flaws — but there’s hardly ever a flaw you can’t fix’, Tea Tsnobiladze said.

The majority of the workers that spoke with OC Media said that during the first year the factory was open, the flaws were not a problem, and that the management only started to bring up the allegedly shoddy workmanship of employees when they stopped paying salaries on time.

According to the Georgian Labour Code, employees are entitled to 0.07% of interest on their salary for each day it is late; Kutex has not delivered on this obligation.

The day of the protest, Tsnobiladze is elected to lead the negotiations with management alongside two other women from the factory. But soon it becomes clear that the owner won’t be present at the table — and there will be no salaries today.

After going through the problems in the air-conditioned office upstairs, negotiators announce the news to the women who are waiting below, in the dark, stuffy factory hall.

It is clear that many of them expected immediate results, but the workers manage to overcome their disappointment and sign on to create a new union. So far, all of them are unhappy and eager to unite — but it’s unclear whether they’ll manage to keep together under pressure from the management, refuse the quick deals, and distribute responsibilities within the union committee.

All of these are problems that usually emerge soon after workers’ primary demands have been satisfied.

Solidarity forever?

Imeri Ltd is one of Georgia’s oldest textile companies — it was founded as a joint-stock cooperative in 1928 and survived through the collapse of the Soviet Union. In 1997, they got their first international client. They’ve also been supported with a ₾812,700 ($275,000) investment from the Enterprise Georgia programme to create an additional 120 workplaces.

At the moment, Imeri is one of the largest textile factories in the country and works with both international and domestic brands.

The factory employs around 450 people, of which 320 are tailors.

On paper, it is also one of the labour-friendliest workplaces in the country. In 2016, they received the WRAP-gold certificate of compliance from the Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP), a not-for-profit labour standards advocacy group initially created for American clothing companies. They were also named employer of the year by Kutaisi City Hall in 2015–2016.

A former worker who has since relocated to France told OC Media that in her experience of working at Imeri, the company was far from worker-friendly.

Ana (not her real name) began work at Imeri as a tailor in 2013. She stayed at the company for four years. She describes the experience as four years of ‘living in a madhouse’.

When she was hired, Ana was told she would work from 9:00 to 18:00, but she often stayed longer. According to her, nothing she was told at her job interview turned out to be true.

Her salary depended on fulfilling a monthly quota, which, she said, was set so high as to be impossible for a person to accomplish.

‘The most I made in that factory [in one month] was ₾445 ($150) — after we worked for five days a week from 9:00 till 22:00. Other times I would receive anything from ₾250–₾300 ($84–$100), but I was doing far more work than I was being paid for.’

Ana told OC Media that the company took pains to hide the reality of working conditions in order to protect its reputation.

‘There was a WRAP commission that came for a checkup in 2016. We were told by the directors to [tell the inspectors] we didn’t work Saturdays and that our working hours were normal, that we were satisfied’, Ana said. ‘We went to the interview room one by one, and on our way out, someone from the administration would meet us at the door, asking what we had said.’

Factory Director Maia Simonidze, who is also Imeri shareholder and the chair of Imeri’s board of directors, confirmed to OC Media that the management could have requested the workers to give positive feedback. She said, however, that the interviews themselves were confidential and the staff could have expressed their concerns openly, if they so chose.

She also claims that, according to the contract they have signed with the workers, the company pays 30% more for every extra hour of work, and that often, they pay even more than that.

Workers at the factory went on strike repeatedly but found that their union refused to stand by them.

‘What could we do? There was no unity’, Ana said, adding that it was mostly Imeri old-timers that were the union leaders, 70–75 year-olds, who didn’t want to jeopardise their positions in the union for the sake of younger workers.

Yellow unions and a bad economy

In Georgia, many industrial unions do not represent the workers, but rather serve the interest of business owners. Such ‘fake’ organisations are known as ‘yellow trade unions’.

Eto Saginadze, who has worked at Imeri for over six years, says that the Imeri union is firmly on the side of the factory owners. She says that any recent improvements in working conditions have happened in spite of the union, not because of it.

‘[The trade unions representatives] were not chosen by the people and they don’t serve the people, I’m not afraid to say it openly’, Saginadze told OC Media, adding that the union leadership had been staffed with company managers.

Maia Simonidze told OC Media that since the collapse of the USSR, the company has been engaged in a battle for survival.

‘This area was seriously developed in Georgia during [the Soviet period] — there were 40 large-scale textile factories here, and Imeri was one of them’, she said. ‘From those large factories, only two are left — Batumtex, which was sold to Austrian investors, and us, who remained Georgian.’

With little connection to outside markets and little demand within Georgia, the company first produced military uniforms, even though, Simonidze says, ‘we knew it was not “real” work’. It was only in 1997 that they received their first international orders, from German company Barbara Lebek.

Since then, the company has produced clothing for a variety of international companies and has recently inked a deal to produce clothing for luxury Italian brand Moncler.

Despite the company’s success, Simonidze said that they have struggled with high staff turnover and a labour shortage — trained specialists in particular.

In an interview with a Mkhare, a Kutaisi-based media outlet, she blamed the shortage on a lack of motivation among job-seekers and an ‘epidemic’ of workers choosing to seek employment abroad.

But when speaking with OC Media, she admitted that low wages are also to blame.

‘At the moment, we can accept 20 more people to work here, but they are not coming, and I understand why. Because the salary is not as high as the work demanded from them.’

As for the role of the unions, Simonidze said she saw it as entirely positive.

‘Our factory has always been unionised — since 1921’, she said. ‘I am a union member myself and I believe that it has serious power.’

She added that she also understands that workers may also be frustrated with the union and its leadership, but ultimately it is not the company’s fault, as the union is not under the responsibility of company management.

‘It’s quite possible that workers might be unhappy with union’s current chair – it was not selected by them but by the [union’s] head office in Tbilisi’, she said.’

Giorgi Diasamidze, told OC Media that Simonidze’s claim is spurious and that the union’s chair is never appointed by the head office. Rather, he said, the chair should always be elected by a general vote of union members at the worksite.

However, he added that he doesn’t know how the union chair at Imeri came into her position.

The union’s current chair, Manana Deisadze, who has been in her position since 2014, told OC Media that she was neither appointed by the union office, nor elected by a general vote. Rather she said that she was elected by a ‘committee’ of five employees of the factory.

A losing battle

However, even when a trade union is rooted in the workers and is of the sort where the chair of a company’s board of directors cannot be a member, it does not guarantee success.

Marina Oboladze, a 61-year old former worker and union activist at Georgian Textile Ltd, was fired in 2018 along with 15 workers due to what the company called a ‘staff reduction’ — though Oboladze believes the company had an ulterior motive.

‘They just got rid of me because I couldn’t stand iniquity and was always voicing my concerns’, she told OC Media. She was fired shortly after requesting to speak to the factory owner about working extra hours, for which she says said she and other workers had not been compensated.

With legal help from the union’s head office, Marina appealed to the court, but instead of rehiring them, the company has paid them two months compensation. However, the payout only included the base rate.

‘Our salary was ₾1.30 per hour, plus bonuses for good quality’, Oboladze said. ‘Discipline, and performance — we never got compensated for those. Just ₾250 ($84) each’.

Oboladze and two other workers decided to lodge another appeal and are still waiting for the results.

‘The others didn’t go to the court’, Marina said. ‘They didn’t want to pay the expenses.’

Marina works in another textile factory now, where the salaries are low. Even though she’s dissatisfied, she refrains from discussing it with the management.

‘After what happened, I’m afraid to raise my voice. I’m scared to lose this job too’.

Small victories

After the owner of Kutex was a no show on the day of the protest, the newly unionised workforce took their battle against the company to court. With the help of the legal team at the Agriculture, Light Industry, Nutrition Industry, and Manufacturing Industry Workers union’s headquarters in Tbilisi, a court case was started.

The judge ruled in favour of the workers and the company was ordered to sequester (i.e. sell-off) assets in order to pay the workers the wages they are owed.

Kutaisi labour union head Irakli Mkheidze believes that the sequester is more than just a financial victory.

‘After the sequester, the people of Kutex realised that the court can be a way to achieve justice’, Mkheidze told OC Media. ‘These people often think that the employer, being financially powerful, can bribe the court. These prejudices make them lose hope that the court can defend those who are weaker’.

Mkheidze sees reasons for optimism for the Kutex workers, despite the difficult conditions for organised labour in Georgia.

‘First of all, there are several leaders here who believe they will achieve justice. People like Tea ignite faith in others and that means a lot. [Secondly], the employees believe that if they lose this job, with their skills and experience it will be easy to find a new one in the same field.’

But despite the victory, Mkheidze believes the Kutex case showcases the weakness of labour in Georgia, which can only be addressed by wider systemic change.

‘Labour litigations appear when labour condition abuses are large-scaled’, Mkheidze said. ‘Employees prefer to endure small violations and stay silent and not spoil their relationship with the employer. This fear accumulates the problems that result in the final explosion [a strike].’

As a result, grievances, he said, are only addressed after prolonged suffering by the workers. He says that international examples show that wider unionisation among the Georgian workforce would ensure that such grievances would be addressed earlier, or not occur in the first place.

For this to happen, however, the social attitude towards unions must change.

‘There are remnants of Soviet cliches that a person who raises their voice for justice is just a skilful manipulator that seeks their own benefit’, he said. ‘This mentality affects a whole range of industries in the country.’

For the moment though, he concludes, it is, in fact, Kutex’s poor treatment of workers that gives them leverage. By violating their rights to the extent that it has, the company has lost their ability to punish them for any further organising and mobilisation — now the workers ‘have nothing to lose’.

This was the first part of a multi-part investigation into Georgia’s textile industry. It was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of FES.