Nagorno-Karabakh’s government announced on Saturday that the region would accept humanitarian aid sent by the Russian Red Cross through Azerbaijan-controlled territory. The announcement came hours after the parliament’s election of a new president.

While Azerbaijan has pushed for Nagorno-Karabakh to accept aid sent via the Aghdam–Stepanakert road for weeks, sending an aid convoy to the line of contact in late August, the government in Stepanakert had previously maintained that it would only accept humanitarian aid sent through the Lachin Corridor.

[Read more: Azerbaijan blocks French convoy from reaching Nagorno-Karabakh, sends its own]

Hours after former National Security Service head Samvel Shahramanyan took on the presidency, Nagorno-Karabakh’s government information agency announced that aid delivered via the Aghdam–Stepanakert road would be accepted due to ‘acute humanitarian problems’.

Shahramanyan replaced Arayik Harutyunyan, who resigned on 31 August after suggesting that his continued presence in the role could be an obstacle to negotiations with Azerbaijan.

According to the statement, the Russian government launched the initiative to provide humanitarian aid to the region, and was accepted by Nagorno-Karabakh’s government due to the need to address the humanitarian issues caused by Azerbaijan’s blockade of the region.

It added that an agreement was reached ‘at the same time’ to allow Russian peacekeepers and the Red Cross to resume their transport of humanitarian aid via the Lachin Corridor, which connects Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

Later that night, Hikmat Hajiyev, the assistant to Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, told media that Russian Red Cross aid deliveries would go via the Aghdam road ‘in coordination’ with the Azerbaijani Red Crescent Society.

‘This is a separate agreement and should not be confused with the ICRC’s proposal to simultaneously open the Aghdam–Khankendi [Stepanakert] and Lachin–Khankendi roads for the delivery of humanitarian aid’, said Hajiyev.

Hajiyev added both that the government in Stepanakert had ‘refused’ the offer to simultaneously open the Aghdam and Lachin roads, and that, were the Lachin road opened, Azerbaijan’s ‘customs and border control [regime]’ would need to be observed.

As of Monday evening, Armenian and Azerbaijani media reported that a Russian Red Cross lorry remained stationed in Barda, north-east of Aghdam.

According to Azerbaijani media, the Russian Red Cross was awaiting approval from the Red Cross headquarters in Geneva to enter Nagorno-Karabakh via Aghdam, as it only had existing approval to enter via the Lachin road.

Tigran Abrahamyan, an Armenian opposition MP, on Monday told Armenian media that the delivery of aid had stalled because Azerbaijan had introduced new conditions regarding the opening of roads.

‘It [offers] only the opening of the Aghdam road and [stipulates] the entry of Azerbaijani [Red] Crescent trucks into the territory of the Republic of Artsakh, in addition to the Russian truck. Naturally, this was not acceptable by the authorities of Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh]’, said Abrahamyan.

Azerbaijani Red Crescent vehicles remain stationed on the line of contact in Askeran.

The Lachin Corridor, the only road connecting Nagorno Karabakh to Armenia, has been blocked since December 2022, with delivery of humanitarian aid blocked since June.

[Read more: ‘Bread is all we have’: Nagorno-Karabakh’s population faces threat of starvation]

Azerbaijan has blocked multiple attempts to deliver aid to the region via the Lachin road, stopping an Armenian delivery of aid in July, and two French humanitarian convoys in August.

Civil obstruction

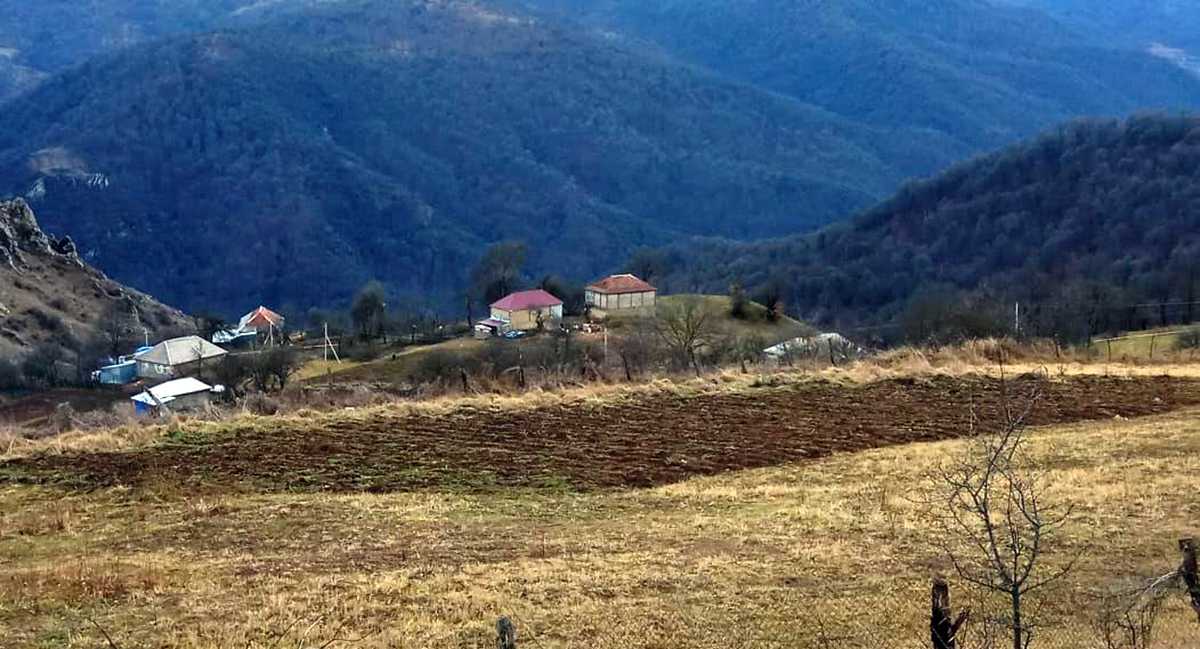

On 18 July, residents of Nagorno-Karabakh gathered to establish a barrier on the Aghdam–Askeran road, demonstrating their objection to Azerbaijan’s suggestions that the region receive humanitarian aid from Baku. They returned to the point at the entrance to Askeran on 29 August, after Azerbaijan sent a shipment of humanitarian aid from Baku.

On Sunday, Armenian media reported that Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians continued to obstruct the Aghdam road.

One participant told Civilnet that the aim was to prevent any cargo entering Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijani territory.

‘Azerbaijan will try to show that Artsakh is not surrounded, and force all of Artsakh’s food supply to come from the territory of Azerbaijan’.

They also stated that senior government officials had visited the site, and told protesters that if the Aghdam road was opened, the Lachin corridor would be opened ‘immediately’ afterwards, while if goods were not accepted via that road, it was possible that Azerbaijan might escalate the conflict at the border and potentially launch a full-scale war.

On Monday afternoon, the German Embassy in Yerevan announced that it would be providing the Red Cross with a €2 million ($2.1 million) for ‘its life-saving work in the region’.

‘It is important that the aid arrives now, which is why we are committed to open humanitarian access’, the tweet read.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.