Opinion | A year after I ran in Azerbaijan’s rigged election, militarism now shapes politics

The ‘victory cult’ is the latest tool being weaponised by the government in Azerbaijan’s electoral politics.

In Azerbaijan, the electoral institution suffered its final and most decisive blow in the aftermath of the 2020 parliamentary elections, which witnessed the active participation of a relatively larger number of independent-minded young candidates.

Held on 9 February, just months before the outbreak of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, these elections briefly revived a fragile hope that the authorities might tolerate the democratic election of a handful of critical young voices as MPs. It was widely believed that such an outcome could soften the political environment, address certain deep-rooted social issues, and even bring incremental reforms within state institutions. Consequently, both civil society actors and parts of the wider public regained a limited sense of trust in the electoral process. Several youth activists and organisations even formed electoral blocs to run collectively.

Yet, contrary to expectations, the authorities refused to recognise the elected young deputies and instead appointed, in their place, their own hand-picked candidates. According to the preliminary assessment of the International Election Observation Mission of the OSCE/ODIHR, PACE, and the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly, ‘restrictive legislation and the political environment prevented genuine competition in the 9 February 2020 early parliamentary elections in Azerbaijan, despite the high number of candidates’.

For many, this marked the last election in which civil society still held even residual faith in the possibility of change through formal political institutions. By the time of the snap parliamentary elections on 1 September 2024, this trust had vanished. The political atmosphere was devoid of genuine electoral competition, and unlike in earlier contests, civil society displayed little engagement.

The pre-election campaign was marked by the detention of one peace activist who was later released, the arrest of another, the disqualification of independent candidates on technical grounds, and a widespread sense that the results were already predetermined.

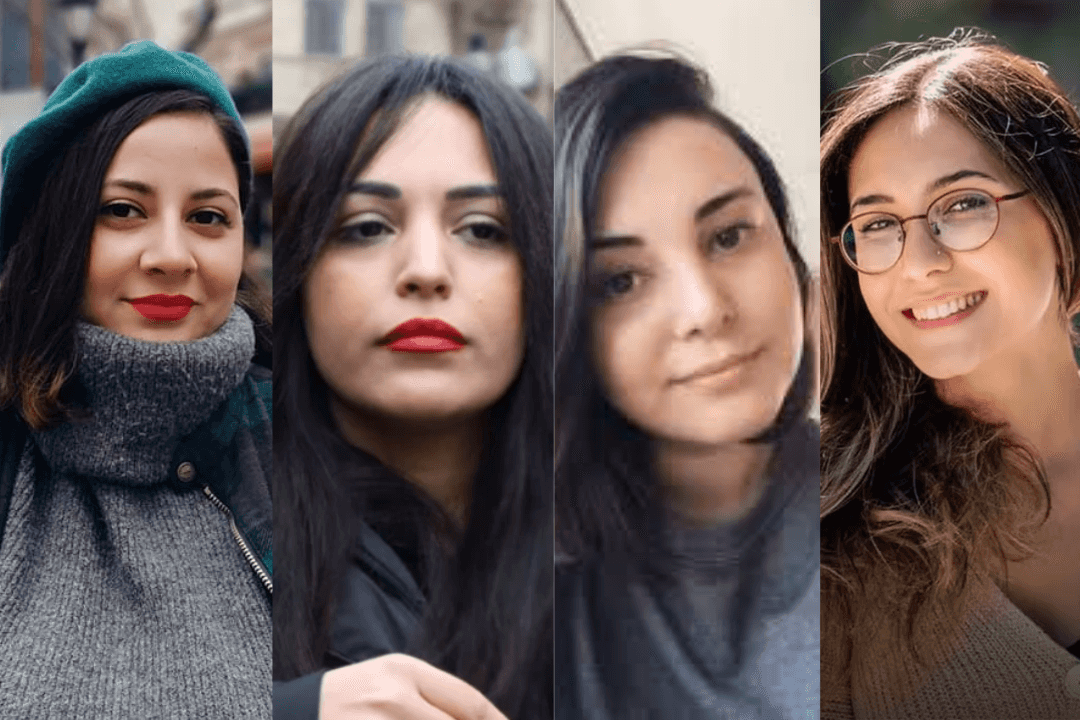

Those few independents whose candidacies were formally registered understood in advance that they would not be allowed to win. I was among them.

Running from the 70th Neftchala electoral district, my candidacy was officially registered, and I secured 2,300 votes. Nevertheless, the authorities artificially inflated the votes of my opponent and declared them the winner, once again reinforcing the perception that elections in Azerbaijan serve as instruments of control rather than vehicles of representation. Despite the fact that all evidence and video recordings of electoral fraud were submitted to the Central Election Commission (CEC) after the election, the CEC annulled results in only six polling stations. In response, we collected and submitted all the documented evidence and materials to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

During the campaign period, I also learned that a criminal case had been opened against me by the State Security Service (SSS). Apparently, the SSS was angered by the success of my campaign in the Neftchala district.

As for the other candidates in the election, although there were a total of eleven candidates in my district, nine of them were effectively representatives of the ruling authorities. To stage the appearance of competition, the authorities placed their own candidates on billboards under the label of ‘independent’. One such candidate, whose victory was predetermined and well-known both to herself and to the local population, was Tenzila Rustamkhanli, wife of Sabir Rustamkhanli, the former deputy of Neftchala district and chair of the Citizens’ Solidarity Party, a party portrayed in Azerbaijan as ‘independent’, yet in reality functioning as a pocket opposition.

Throughout the campaign, Tenzila Rustamkhanli carried out her propaganda by framing me as ‘pro-Armenian’, a ‘Soros agent’, and an ‘LGBT supporter’, engaging in smear campaigns among local residents. She openly argued before government officials that a criminal case should be launched against me, deliberately portraying me as an ‘enemy within’.

Nevertheless, despite being pre-selected by the authorities, her reliance on such shallow narratives failed to capture the genuine interest of the local population. The people of Neftchala largely ignored her propaganda, seeing her as an instrument of the system rather than a genuine representative.

Yet, as expected, although I had been democratically elected by local voters, the authorities appointed their pre-selected candidate, Tenzila Rustamkhanli, to parliament.

What was different, however, was that alongside the old mechanisms of electoral fraud, the government increasingly deployed militarist values as political tools.

As American feminist international relations scholar Cynthia Enloe reminds us, militarism does not stay on the battlefield; it spills into everyday life, shaping how people and institutions function. Building on this perspective, the 2020 war marked not only a decisive military and political victory for Azerbaijan, but also the beginning of a new discursive era in its media and politics.

Practices once tied to Soviet commemoration of 9 May, the ‘sacred history’ of victory in the Great Patriotic War (the term used by the Soviet Union and its successor states to refer to World War II), were repurposed to glorify Azerbaijan’s new ‘victory’.

Television, films, and other cultural productions were mobilised to anchor the politics of remembrance around Nagorno-Karabakh. References to the triumph over fascism, long used rhetorically in the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, gained renewed prominence during and after the 2020 war, reflecting the regime’s increasing reliance on militarised symbolism to consolidate its authority. Public intellectuals who enthusiastically embraced the ‘victory in war’ narrative described it as the emergence of a new nation. They claimed that the people had been ‘reborn’, through suffering, battles, and horrors, yet also with excitement and even euphoria, this time as a political nation. The parents of fallen soldiers, ‘martyrs’, were turned into symbols of loyalty and instruments of political pressure.

Across the country, new ‘martyrs fountains’, giant posters of soldiers hanging from supermarket ceilings, ‘victory’ signs in front of wedding halls, and school performances where children were forced to dress up and play ‘wounded soldiers’ became ways of embedding militarism into everyday life and values.

This visual and symbolic environment did not heal society’s wounds; instead, it turned into a mechanism of state control.

Slogans such as ‘Iron Fist’, ‘Victory’, and ‘Karabakh’ were not merely rhetorical devices in the government’s political vocabulary, they also functioned as displays of power for the domestic audience. The authorities worked to ensure that citizens would encounter these values constantly in daily life, internalise them, and refrain from questioning them.

Criticism, meanwhile, was equated with treason. Anyone who challenged state officials or political authority was branded ‘pro-Armenian’, and those who opposed the war were accused of betraying the homeland.

The snap elections of 1 September 2024 provided stark examples of this trend.

In one polling station, when an observer attempted to flee with fake ballots as evidence, the station chair threatened him by saying: ‘If you don’t return the box, I will report you to the police for insulting a martyr’s mother’. This incident clearly illustrated how nationalist and militarist values had been weaponised as protective shields for electoral fraud.

In my electoral district, the ruling party’s candidate, Tenzila Rustamkhanli, deployed martyr families as ‘observers’ in all polling stations. Their presence not only created a symbolic image of respect, but in practice, turned them into participants in the execution of electoral fraud. Independent observers who protested were accused of ‘insulting the families of martyrs’.

Ultimately, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War brought Azerbaijan not only military victory but also the consolidation of militarist values as a systematic mechanism of control.

The Azerbaijani case demonstrates that in post-war contexts, militarist values function not merely as a constitutive element of national identity, but also as a technology of authoritarian legitimation.

The snap parliamentary elections of 1 September 2024 are already a year behind us. Yet their consequences remain. The 125 MPs gathered in the parliament were not chosen by the people, and the price of this absence of representation is still paid by the many citizens whose voices are missing.