Opinion | As the Church and government clash in Armenia, democracy falls victim

A bitter feud between state and church risks eroding public trust and weakening Armenia’s democratic institutions.

After the Velvet Revolution in Armenia, it was clear that the relationship between the new government led by Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and the Armenian Apostolic Church would not be smooth. The post-revolutionary authorities were unlikely to show tolerance toward an institution that had been closely tied to the former regime and, in many ways, enabled its corrupt practices. Many senior clerics, including Catholicos Karekin II, had longstanding ties to the previous leadership, remaining silent on injustice while benefiting from political proximity.

Since then, Church-state relations have gone through predictable cycles, sometimes cold, sometimes confrontational. But what we are witnessing now is something far more serious: a public clash that has become vulgar, personal, and destabilising, as the Prime Minister and his wife have accused the Catholicos and other clergymen of pedophilia and violating celibacy vows. And in this escalating conflict, it is Armenia’s fragile democracy that falls victim.

In a healthy democracy, no institution, be it the Church, the Army, or civil society, should be immune from criticism. Public scrutiny and open discourse are essential for institutional growth and public trust. However, the aggressive and inappropriate language used by Prime Minister Pashinyan in addressing certain clergymen has not served reform, it has only deepened polarisation. Many citizens find it hard to see how this rhetoric contributes to constructive change. His tone has been echoed by his wife, Anna Hakobyan, and political allies, further degrading the level of public discourse.

At a certain point, this ceased to be political critique and became a personal campaign to humiliate and delegitimise the Church, an institution that, for many Armenians, remains a core element of national identity. Unsurprisingly, this provoked a backlash. Regardless of whether Catholicos Karekin II would pass a ‘background check’, many Armenians still view him as the face of the Church, and an attack on him is widely seen as an attack on the Church itself. In a society already fractured and in need of unity, this approach is not only unnecessary but politically damaging.

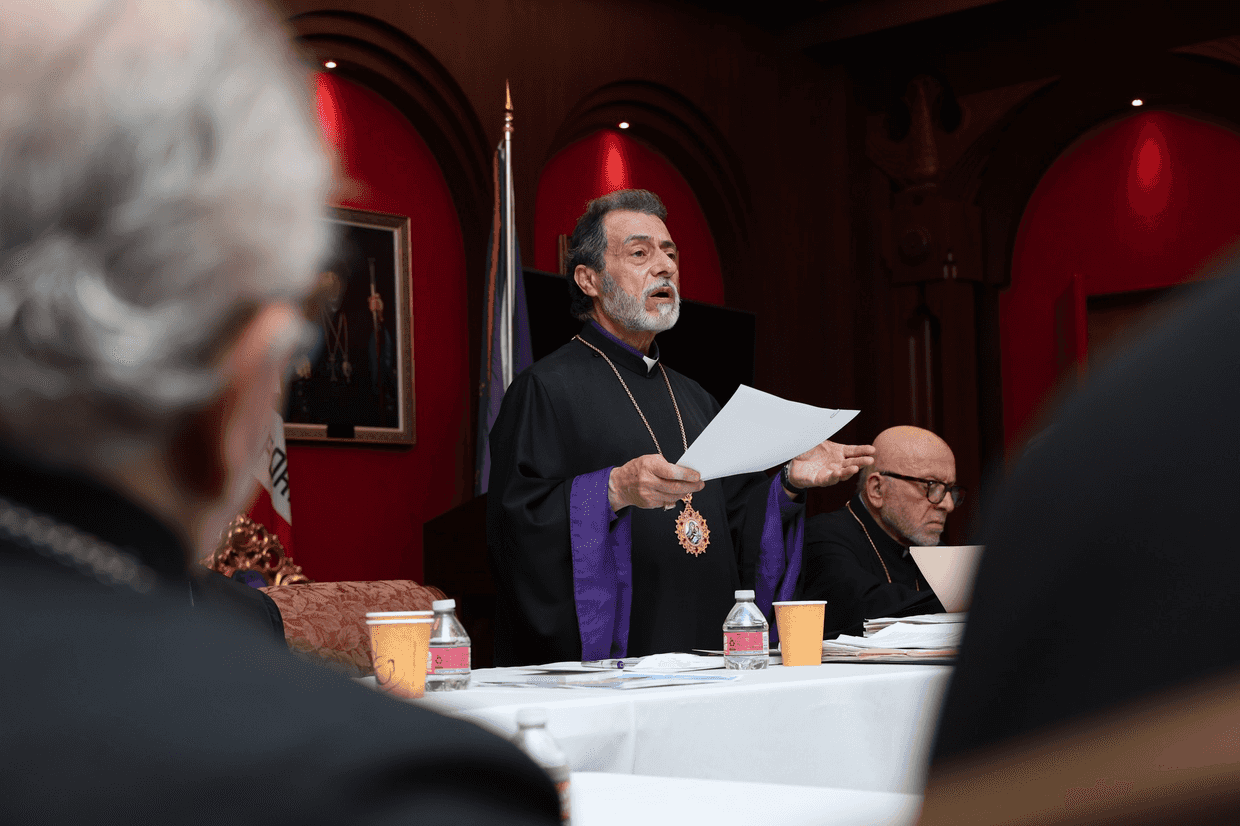

From pulpit to the podium

Some speculate that the government seeks to weaken a historically respected and independent institution to consolidate control. Yet two points must be made. First, while the Church retains symbolic power, Catholicos Karekin II is not uniformly respected, largely due to his associations with the discredited former regime, and the ever existing accusations of clergymen being corrupt, involved in fraud and scandals. Second, the Church can hardly be seen as an independent institution when its leading figures have openly aligned with political forces, including elements of the regime rejected by the Armenian people in 2018.

Since the revolution and especially after the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, the Church has not remained a neutral actor. Its longstanding alliance with the previous regime damaged its moral credibility. During the years of authoritarian rule, it often turned a blind eye to corruption, social injustice, and human rights violations. In some cases, it even lent legitimacy to these abuses. Rather than reckoning with this legacy, the Church has become increasingly political.

In 2019, a working group was formed on State-Church relations, which became dysfunctional largely due to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. Following the 2020 war, the Church moved further into the public sphere. In 2023, Bishop Bagrat Galstanyan emerged as a leading opposition figure under the ‘Tavush for the Homeland’ movement, blurring the line between spiritual guidance and political activism. The Catholicos himself has offered platforms and blessings to political leaders, reinforcing the Church’s partisan stance.

In doing so, the Church has weakened its claim to be a unifying force in national life. By taking sides in the political struggle, it has contributed to polarisation rather than healing it.

A secular state under strain

Armenia is a secular state with no official religion. The Constitution recognises the historical role of the Armenian Apostolic Church while enshrining the principle of separation between Church and state. This should be the foundation for mutual respect and institutional restraint. While the Church may engage in public debate, it should not become an active participant in party politics, especially alongside forces that have shown little respect for democracy or human rights.

The constitutional balance is now being undermined by both sides. The government, with its antagonistic rhetoric, has failed to maintain the dignity of institutional interaction. The Church, by aligning with opposition movements and directly engaging in political struggle, has abandoned the political neutrality expected of a religious institution.

The legal framework regulating Church–state relations, adopted in 2007, is vague and outdated. It needs to be revised, but through respectful and transparent dialogue between both institutions. Without clear legal boundaries, institutions fall into power politics and in this case, democratic norms are the first to erode.

There are no winners in such a conflict, but public life suffers. Members of the public watching this spectacle are left disillusioned. When they see state officials mocking clergy and clergy campaigning in the streets, they do not see this as populism, they see it as a failure of democracy, a sign that all power is self-serving and no institution represents their interests.

Armenia has held multiple free and fair elections since the revolution, but that is not enough. Democracy also requires trust in institutions, norms of civility, and mutual restraint. It is the responsibility of the government to treat other institutions with respect, and of the Church to act in the public interest rather than as a political faction. Without this, democratic culture cannot survive.

This conflict must be resolved through the rule of law. Armenia needs a modernised legal framework on Church–state relations, one that defines institutional roles, safeguards independence, and enables constructive dialogue. A commission convened by Parliament in consultation with the Church could be a starting point. Restoring civility and constitutional order will not come from victories in the streets or on social media.

Democracy rarely collapses in a single dramatic moment. More often, it is eroded over time through disrespect, polarisation, and institutional decay. This crisis is a test of Armenia’s democratic maturity. If Church and State continue this path of provocation, the greatest casualty will be public life itself — the very foundation of democracy.