Opinion | Can Azerbaijan really seek peace while it continues to repress its own people?

For true peace to happen, Azerbaijan must go beyond external agreements and look within to create change.

On 8 August, a peace agreement was initialled between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Washington, DC. While this document represents an important step in the diplomatic sphere, the question of how it will be received domestically and translated into reality still remains open.

This contradiction recalls the Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung’s concept of peace: the cessation of war constitutes negative peace, while the elimination of structural violence, injustices, and discrimination constitutes positive peace. Thus, peace is not merely the end of war. If structural violence, corruption, discrimination, poverty, and restrictions on freedoms persist in society, this is only one side of the coin, a negative one.

Among Azerbaijani civil society, hope arose that after the Washington meeting that political prisoners would be released, including, most notably, peace activist Bahruz Samadov. Such expectations were fuelled by a recording of a conversation between Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and US President Donald Trump during which the issue of Armenian detainees in Azerbaijan was raised. According to the footage circulated on social media, Trump is heard telling Pashinyan: ‘Alright, I will tell him [an apparent reference to Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev] to do it’.

However, since then, nothing has happened. Neither Samadov nor any other political prisoners have been released, and no reports about future plans for their release have appeared in the media. Instead, in the Azerbaijani context, the initialled peace agreement has appeared only as a manifestation of negative peace. This is because political prisoners still remain in the country, independent media has been dismantled, borders remain closed, and civil society participation has been reduced to zero.

If independent media is dismantled, their staff imprisoned, and peace activists remain behind bars, how will Azerbaijani society perceive the alleged peace the Washington agreements intend to bring? Is the release of these activists and the functioning of independent media not essential for the realisation of genuine peace?

Since 2020, the ‘iron fist’ rhetoric has become central to both state discourse and the dominant media framework in Azerbaijan. The phrase ‘iron fist’ came to function not only as a military narrative directed against the external ‘enemy’, but also as an ideological tool for keeping the domestic audience under control. This rhetoric both confines public discourse within a militarist framework and silences any voice questioning the legitimacy of the regime by branding it as ‘treason’. For example, any attempt to expose corruption or criticise electoral fraud is suppressed with labels such as ‘pro-Armenian’ or ‘treason’.

At the same time, Aliyev has led a relentless campaign to eliminate dissenting voices, dismantling what little media pluralism once existed.

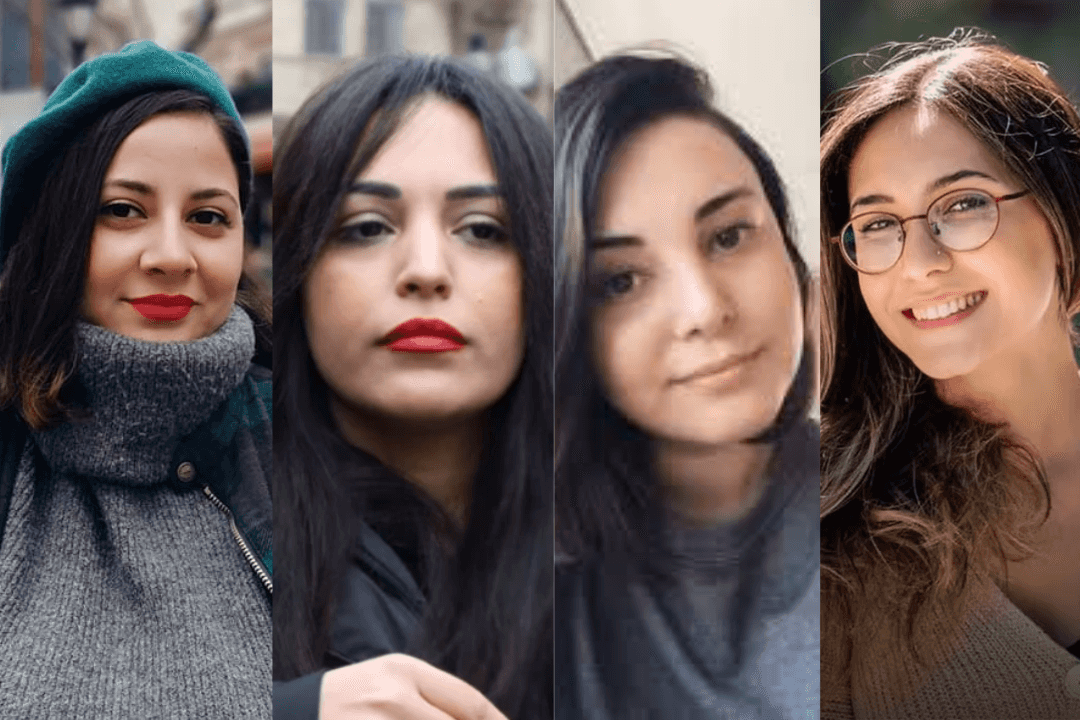

Towards the end of 2023, seven employees of the independent media outlet Abzas Media were arrested. The following year, seven journalists from Toplum TV were detained, followed by another seven from Meydan TV. All were arrested on fabricated charges. Ranked 167th out of 180 countries in the latest World Press Freedom Index, Azerbaijan has again confirmed its reputation as one of the most repressive countries for journalists in the world.

In turn, Azerbaijani pro-government media has for years constructed an ‘enemy’ narrative, entrenching hate speech and enmity towards Armenians. Embedded into societal memory, such narratives cannot simply dissolve overnight.

The realisation of peace also depends on everyday life, on the social and civic interactions established between ordinary citizens of both nations. One necessary step for this is the reopening of land borders.

Since 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began, Azerbaijan’s land borders have remained closed. Most recently, in June 2025, the government extended the closure until 1 October, still citing the pandemic. However, in his speech on 24 September 2024, Aliyev linked the closure of borders not to public health but to the geopolitical situation, describing it as the only way to ensure internal security. This shows that in order to keep borders closed, the regime continuously needs new narratives. Yet their closure negatively affects both citizens’ lives and the peace process itself.

If we are speaking of genuine, positive peace, then the normalisation of relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia must also be consistently communicated to the public and made transparent.

Against this backdrop, peace in Azerbaijan may be welcomed symbolically, but many questions are still left unanswered. For instance, when someone criticises corruption, or challenges election fraud, or tells a fraudulent MP ‘you have stolen votes’, will they still be branded as ‘pro-Armenian’ or a ‘traitor’? Or will the government invent a new narrative to delegitimise dissent?

External peace should always align with internal peace. As Galtung’s concept of ‘positive peace’ shows, real peace is not merely the existence of a ceasefire or a signed agreement, but also the strengthening of human rights, freedom of expression, and democratic institutions. Without justice and equality at home, external diplomatic peace remains fragile and unsustainable.

But can a country with more than 350 political prisoners truly change?

Unfortunately, the current peace process is being built top-down, despite the fact that one of the main conditions for durable peace is inclusivity: not only government-appointed representatives but also civil society, independent media, and public groups must be part of the process. Otherwise, ‘peace’ will remain only on paper. Yet those who genuinely strive for real peace are either in prison or forced into exile. Thus, what exists in Azerbaijan today is only ‘negative peace’ — the temporary absence of violence, but with the entrenchment of social injustice.