Opinion | Fourteen years on Rustaveli Avenue — documenting Georgia’s descent into authoritarianism

Despite all the warning signs, there are still some who cannot, or who refuse to see just how far Georgia has fallen. But having worked as a journalist for the past 14 years, I have seen and documented my country’s descent first-hand — on the capital’s central avenue through the lens of my camera.

Rustaveli Avenue, Tbilisi’s central thoroughfare, the site of the country’s parliament, and for decades or more, the primary space in which Georgians have expressed their discontent.

It was here that on 9 April 1989, Soviet troops massacred scores of Georgians demonstrating for their independence. It was also here that in 2007 — under the previous government of the United National Movement — police moved in on a large, peaceful anti-government protest with extreme prejudice.

My own relationship with Rustaveli Avenue as a place of protest began in 2009, documenting opposition protests known as ‘the city of cells’.

Georgian Dream came to power promising to upend the tradition of crushing dissent on the streets, and promising to secure the rights of the press to ensure that they kept their word.

And yet today, the government deploys a number of measures to suppress freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of the press. With each new protest, the levels of violence I expect from the police, from government allies, increase alongside the number of unjustified arrests. Moreover, having spent the past 14 years reporting from the streets, being a journalist in Georgia has now become more difficult, and more dangerous, than ever before.

From humble beginnings

But when did things start to deteriorate so rapidly?

Despite a vast improvement in people’s fundamental rights after Georgian Dream first came to power, even these initial years were far from perfect.

One of the first warning signs that journalists, the free press, was in danger was the kidnapping of Afgan Mukhtarli. Abducted in the streets in May 2017 and handed over to Azerbaijan, his abduction has not been properly investigated. Investigations by the media as well as leaked files from the State Security Service have implicated the Georgian state.

But in terms of freedom of assembly, the warning signs should perhaps have been seen sooner still. Even now, one of the greatest sins of this government was the events of 17 May 2013. Tens of thousands came out to Rustaveli Avenue that day to prevent a couple of dozen queer rights activists from exercising their right to assembly.

I was covering what happened that day, and witnessed how the police allowed a violent mob to pass without resistance. Several people were injured that day, and the activists, who were present still struggle with the trauma inflicted on that day.

[Listen to a first-hand account of the day on the Caucasus Digest: Podcast | A history of homophobic violence]

Perhaps the first time the government was challenged by massive street protests was also the first time I was injured in the line of duty.

Protests had erupted in 2018 following armed raids on several popular nightclubs. I was outside the Bassiani club when police began dispersing protesters. Despite holding my camera and trying to document what was happening, the police took no notice of this. I fell to the ground and a police officer stepped on my neck.

The follow-up protests saw the riot police deployed to Rustaveli Avenue for the first time under Georgian Dream’s rule, when the far-right tried to attack the protesters, though they did not use force to disperse protesters.

That May turned out to be a big month for the government, as anger at the government over the club raids mounted.

The ‘fathers for justice’ duo, Malkhaz Machalikashvili, whose son Temirlan was killed in a special operation in Pankisi, and Zaza Saralidze, whose son Davit was killed in a school fight teamed up to protest what had happened to their sons.

When the court returned a verdict in the killing of Davit Saralidze that many saw as being politically tainted, the backlash was swift. The ensuing protests were peaceful — and indeed resulted in what appeared to be real change (Chief Prosecutor Irakli Shotadze resigned). But later we realised little had changed.

Georgian Dream gets a taste for violence

While the appearance of the riot police in 2018 remained a relatively peaceful one, the same could not be said for their use force in the Pankisi Valley in 2019, in a violent dispersal of local protests against the construction of a hydropower plant. Local rights groups labelled the police actions as a disproportionate use of force.

The riot police used force for the first time on Rustaveli Avenue just a few months later, on the night of 20 June 2019, otherwise known as ‘Gavrilov’s night’.

That night, I was struck by a rubber bullet fired by the police, but this was not nearly as painful as the teargas, which I had never experienced before.

Working after being teargassed becomes almost impossible. It paralyses you for at least 10–15 minutes before your senses return by which time you are likely to get teargassed again.

I remember being very scared that night. I had never covered an event before where police were firing so indiscriminately. I remember thinking that if I stuck close to the police corridor with my press badge and camera, they would surely not shoot at journalists, but as it turned out, they simply didn’t care.

Many journalists were injured that night alongside the protesters.

I cannot forget the first time I saw a photo of my friend and colleague Guram Muradov, whose scars never fully healed.

After this, it seemed almost as if the Interior Ministry got a taste for using the riot police, and they have rarely missed a chance to bring them out since.

Like they did in November that same year, when a couple of hundred people were attempting to blockade parliament after Georgian Dream decided not to keep their word on electoral reforms. So at the end of November, as the winter cold set in, police used a water cannon to soak the relatively small number of protesters.

When the parliamentary elections took place soon after this, people were so dissatisfied with the results, especially after the second round, that thousands walked around 10 kilometres from Rustaveli Avenue to the Central Election Commission, only to be water cannoned there.

I walked with them and arrived to a battlefield. Riot police had already deployed force against those who arrived before us. Despite the entrance of the CEC building being heavily protected by police and fire engines, force was still used.

After the previous protests, I thought I had learnt well how to secure myself from the police force. I hid behind a bus opposite the water canon which I thought would protect me from it. It did, but as I held my camera to my face, a brick struck the camera. I couldn’t really process what happened at the time, but thinking back, I realise my camera may have saved my life that day.

A turn against the media?

Since then, being a journalist has become even more dangerous.

On 9 April 2021, there was a demonstration by a conservative group aligned with the ruling party celebrating what they called “Georgianness”. For the first time that day, I felt outright hostility towards me because I was a journalist. I was scolded by several protesters because of my appearance, and I recall Utsnobi, the protest leader, calling for his supporters not to talk with the media. It was unpleasant and a bit scary.

But no experiences that I’ve described above came close to 5 July 2021. I could talk for hours about 5 July and Pride Week in 2021, but to put it briefly, 5 July was the day when wearing a press badge became dangerous in Georgia.

We took the decision at OC Media in the morning to work undercover that day, which may just have saved us. But I witnessed just off Rustaveli Avenue two of my good friends, with whom I’ve covered numerous events in Georgia, attacked and swallowed by the mob. Both of them received head injuries and spent time in hospital. Two of my other friends were also attacked and received serious injuries that day.

The police, despite their already well-established ability to use force, did not intervene to stop the violence that day. The government has since done nothing but encourage further attacks on the press.

A dark future on Rustaveli Avenue

The year 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Georgia’s subsequent turn from the West, has seen the situation deteriorate further still.

The anti-government protests on Rustaveli Avenue following Georgia’s failure to secure EU candidate status, perhaps the biggest in the country’s history, fizzled out after losing direction.

But 2022 was only a taste of what was to come this year. Georgian Dream’s foreign agent bills going before parliament marked the first time I feared for the very existence of OC Media in Georgia, the Caucasus country we considered the safest when founding the organisation in 2017. We began to consider the possibility of registering abroad if the law passed.

But it was opposed, first and foremost on Rustaveli Avenue.

Again, protests were met with force from the riot police. They were relentless in their use of teargas, and my clothes stank of the stuff for days after the protests ended. However, the protesters did not back down.

This year, I also happened to be the only journalist who observed and documented the 2 June arrest of Eduard Marikashvili on Rustaveli Avenue.

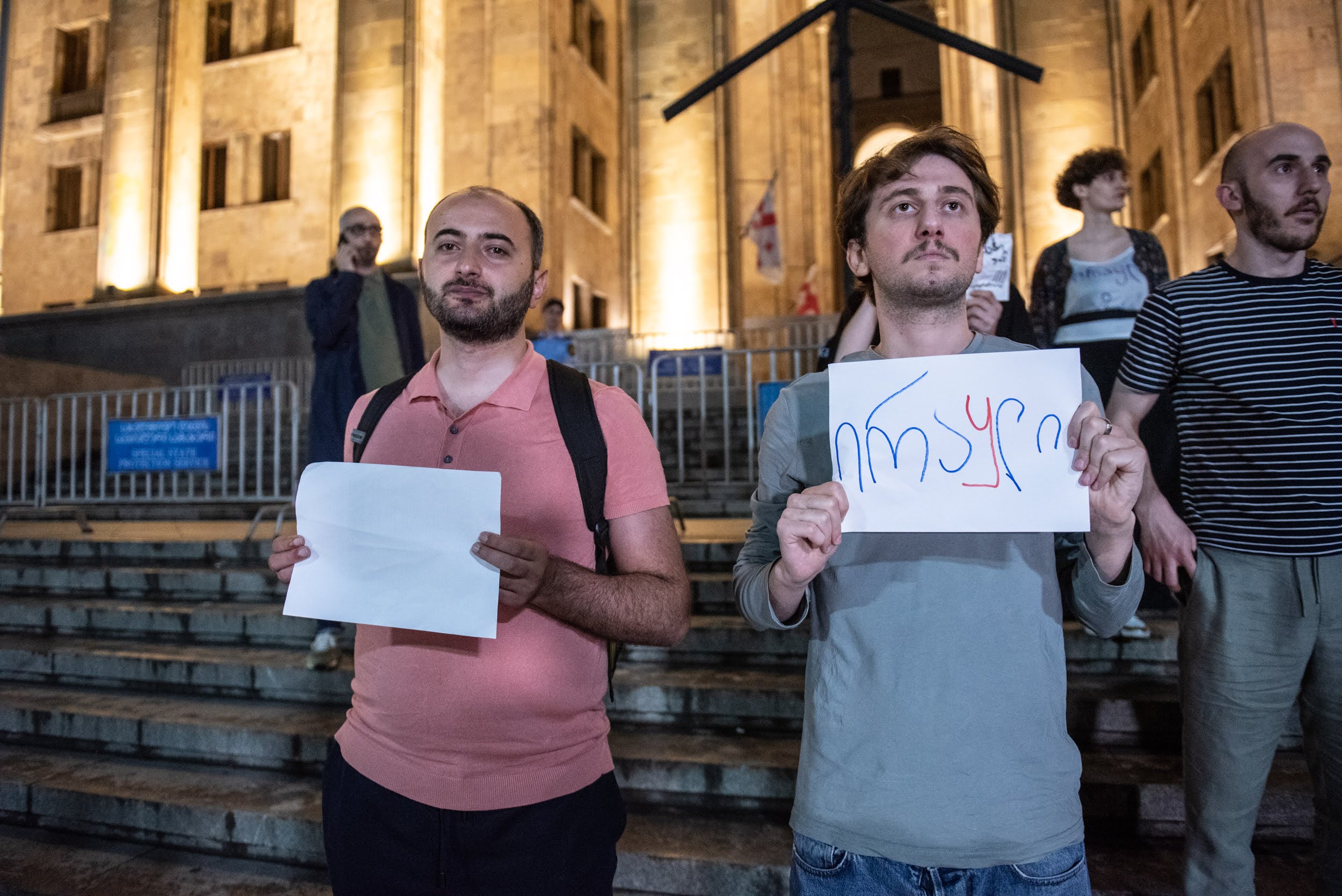

A handful of protesters had gathered, some displaying messages insulting Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili, a demonstration for their freedom of expression after posters with such messages were previously confiscated and destroyed by police.

Several were arrested.

Upon hearing this, Marikashvili, a lawyer and human rights activist, rushed to Rustaveli. He held a blank sheet of paper.

He was arrested.

Marikashvili’s arrest and later conviction for holding a blank piece of paper showed just how challenging protesting has become, with the tightened legislation and courts that do not serve justice, but that have become tools of the government.

His arrest exactly mirrored those seen in the authoritarian regimes in Russia and Belarus.

But despite this, and despite everything else I have documented over the years and in this article, in many of my conversations with decision-makers abroad, I’m met with surprise or even disbelief about just how bad the situation has become.

Among Georgians, such conversations are often marked by a sense of resignation.

But the situation is only getting worse, with further anti-protest legislation expected to soon come into force and the prospect of other tools yet to come that have already been tried and tested to our North, like a queer ‘propaganda’ law.

As we broke the story earlier this year that the Speaker of Parliament had been directly pressuring OC Media’s donors, my colleague, Robin Fabbro and I were in Hamburg, accepting the Free Media Award. One of our fellow awardees was from Reform.by, and during his acceptance speech, he read out the long list of names of journalists behind bars in Belarus. Sitting beside us was another co-awardee from Russia’s iStories, exiled and unable to go home.

In their stories, I saw Georgia’s future — unless more is done now to save our democracy. In their stories, as a journalist, I also saw my own future, in prison or in exile. But until that future comes, I will continue my work on Rustaveli Avenue.