Opinion | Is Azerbaijan sincere with its peace rhetoric or just bargaining with the West?

Despite Azerbaijan’s increasing repression against civil society and media, its relations with Western states have grown increasingly positive.

The wave of repression that began in Azerbaijan in 2023 has completely destroyed independent media, human rights advocacy, and civic activism. The space for opposition political activity has significantly narrowed — as public opinion has been directed towards a discourse of ‘foreign enemies’ and ‘solidarity’ propagated through the government’s own media resources — and freedom of assembly and protest has been restricted to an unprecedented degree.

In response, many activists have left the country, while those that remain struggle to adapt to the new conditions. Those members of civil society who have not yet been directly subjected to repression but belong to the risk group have generally only survived following a chosen ‘silence’ as a means to escape the wave of arrests and preserve their own existence.

It was widely expected that the continuous wave of repression over the past two years would seriously damage Azerbaijan’s relations with Western political institutions and lead to its isolation. Many anticipated that sanctions or explicit demands would be voiced against Azerbaijan, and that the authorities would be forced to make concessions in response. However, none of these expectations materialised. On the contrary, in recent months, the Azerbaijani government’s relations with Western states and political institutions have begun to develop along an upward trajectory.

Despite holding nearly 400 political prisoners, Azerbaijan’s leadership was warmly received by the democratic world during the 6th and 7th summits of the European Political Community held in May and September 2025. At first glance, this approach appears irrational and inconsistent with democratic values. Yet, to understand it, one must look closely at the methodology the Azerbaijani government employs in managing its relations with Western states and political institutions.

First and foremost, it should be remembered that the energy crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned Azerbaijan into an alternative energy route for Europe, replacing Russia. The energy agreements signed during this period have strengthened the geopolitical position of the Azerbaijani government more than ever before. Today, Azerbaijan is making the most of its opportunity to serve as the only corridor to Central Asia between two isolated states — Russia and Iran. It has even reached a point where it can use this leverage to threaten Europe.

The second and more important factor is Azerbaijan’s effective use of the ‘peace and security’ card in the South Caucasus. Particularly over the past two years, the Azerbaijani government has advanced political narratives such as the ‘Zangezur’ corridor and ‘Western Azerbaijan’ discourses, repeatedly bringing up the possibility of new wars in the South Caucasus. As a result, both the EU and the US have been keen to maintain good relations with the Azerbaijani government in order to prevent a new war and accelerate the signing of a peace agreement with Armenia.

This approach can be viewed as a necessary condition for protecting the young democratic system in Armenia and preventing the emergence of a second conflict zone that would serve Russia’s interests. However, although geopolitically rational, this Western strategy has also allowed the Azerbaijani government to maintain its domestic atmosphere of repression, silence the opposition and civil society, and evade accountability for these actions.

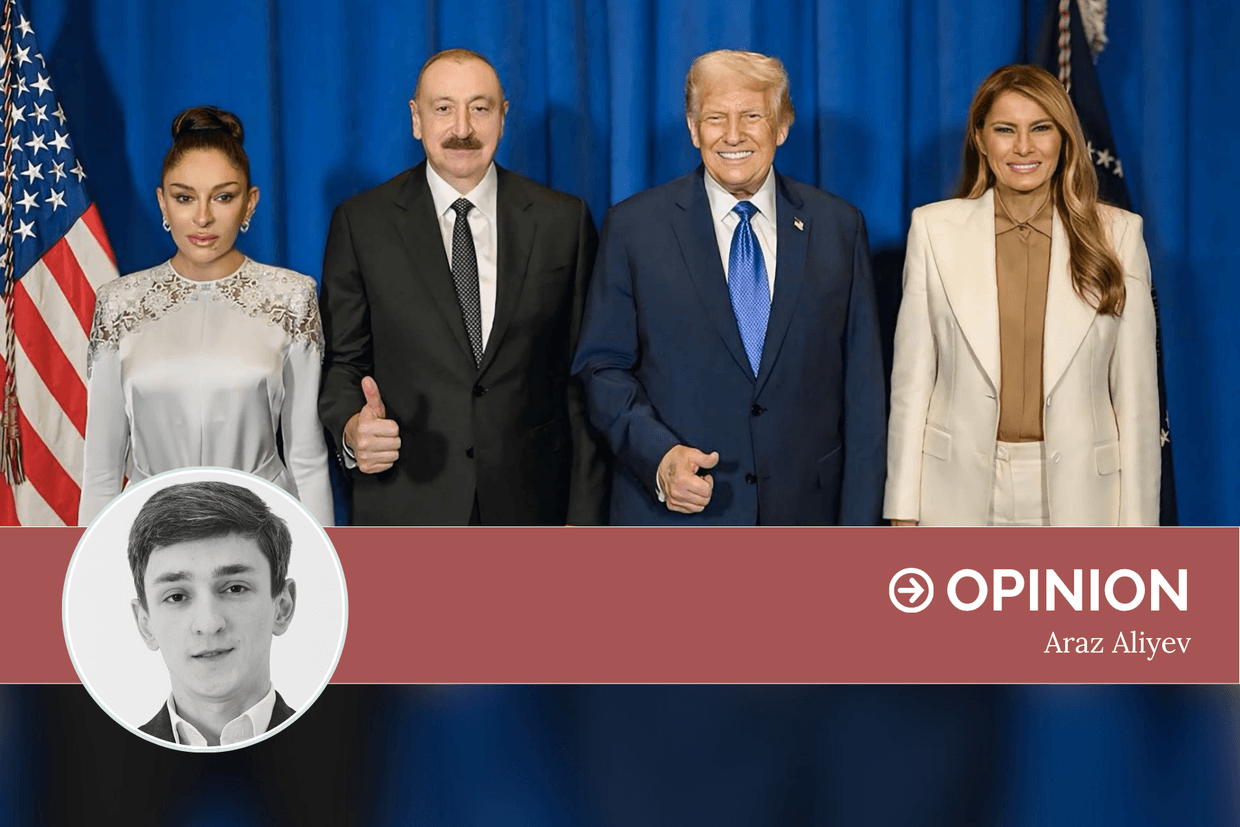

Clearly, for the regime in Azerbaijan, the issue of ‘peace’ has quickly turned into a new and effective bargaining tool. By supporting the peace agenda, the Azerbaijani government has managed to rebuild relations with the West and regain the favour of Western leaders.

As a result, for Western states, the signing of a final peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan remains the top priority in the South Caucasus. Despite the initialling of a peace treaty between the two countries during the Washington meeting in August, the final signatures have not yet been placed, with the Azerbaijani side viewing the forthcoming referendum and constitutional changes in Armenia as the final step toward a comprehensive peace agreement. The absence of final signatures and the uncertainty of global geopolitics keep the issue of peace on the agenda, and as a primary priority for the West.

For Azerbaijan’s opposition-minded public, this recent revival of relations with the West had led to a degree of cautious optimism. In particular, the release of political prisoners in Belarus amidst renewed ties with the Trump administration has sparked hope among domestic audiences that a similar trend could emerge in Azerbaijan as well. Most recently, news about the Azerbaijani authorities allowing a visit by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) to the country, as well as about the government’s planned amnesty decree expected toward the end of 2025, has further strengthened these hopes.

At the same time, there are several critical turning points ahead, including the planned signing of a Strategic Cooperation Agreement between the US and Azerbaijan, and the potential hosting of the European Political Community Summit in Baku in 2028. There are expectations that, in the run-up to these events, the Azerbaijani government may resort to its traditional ‘image improvement’ policy by releasing political prisoners. However, for these expectations to materialise, the necessary conditions that would compel the Azerbaijani authorities to engage in such an ‘image improvement’ process must first be established — and at present, whether such conditions exist remains highly debatable.

The main question remains: is the West genuinely interested in raising issues such as human rights and repression, even at the cost of straining relations with the Azerbaijani government? Or will Azerbaijan continue to be regarded as a ‘reliable partner’ for as long as it remains committed to the peace agenda?

If a final peace agreement is signed, this would eliminate the Azerbaijani government’s most significant bargaining chip — peace and security — in its dealings with the West and create grounds for human rights and democracy to once again become priorities. However, if Western political institutions fail to take concrete actions consistent with their stated values in the lead-up to these events, more serious problems concerning Azerbaijan may arise. Silence would not only render the issue of human rights and democracy in Azerbaijan completely irrelevant but could also ‘legitimise’ the government’s anti-democratic actions over the years.