Opinion | Peace promises and the language of hate: Azerbaijan’s double politics

There is a clear contradiction between Azerbaijan’s peace rhetoric abroad and its war rhetoric at home.

On the world stage, Azerbaijan portrays itself as a supporter of peace. Official speeches and projects are presented as signs of cooperation and reconciliation. But inside the country, the picture is very different: state media and propaganda channels still spread anti-Armenian hate speech.

As a result, the concept of peace does not reach ordinary people on the ground in Azerbaijan. Instead, hatred and hostility continue to shape public thinking, which has become one of the biggest barriers to real reconciliation.

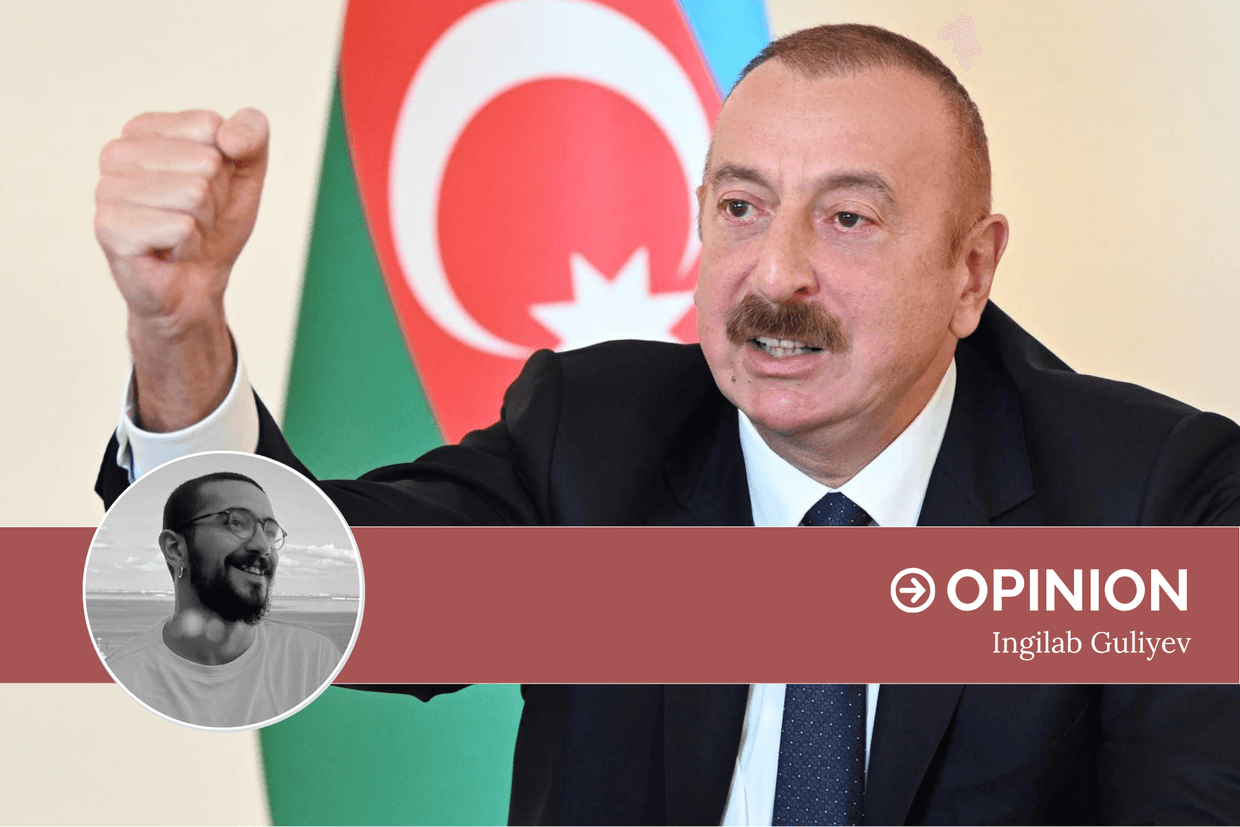

A recent example of this occurred on 21 August, when President Ilham Aliyev gave a speech in Kalbajar during which he said ‘We must always be ready for war […] We want peace. But we must never erase that bloody history from our memory’.

The message had multiple tasks. To the international community, it sounded like a call for peace. But for people inside the country, it held a secondary meaning — a warning that war could return at any time.

Aliyev’s words did not inspire hope; they reminded people of losses and fear. Many reacted on social media with bitter comments like: ‘Send your own son to fight’. These were not just angry words; they showed the deep frustration and pain felt throughout the country. After all, it is ordinary families that have carried the heaviest burden of the war, losing sons, fathers, and brothers.

Before the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, the government promised that ‘a different Azerbaijan’ would come. But this never happened. Poverty, social injustice, and censorship all stayed the same, or became even worse. People see clearly that those promises were empty ones.

The situation of the families of fallen soldiers and wounded veterans is especially painful. Many were left without proper care or support — dozens of veterans, suffering from physical injuries and psychological trauma, burned themselves to death. These tragedies show the silence and neglect of the state.

Even worse, those who tried to speak about these problems were punished. The clearest example is the arrest of the head of the Young Veterans group, himself a war participant who lost one eye in battle. The message was simple: ‘You are a hero if you stay silent. If you speak out, you are treated as an enemy’.

In this situation, official talk about peace sounds empty. Citizens know that the deepest indifference does not come from abroad, but from their own state.

For this reason, people do not only feel war fatigue; they also feel betrayal. The war victory did not bring a better life — instead, hopes for change were buried with those who died.

This tactic is not new. Across the globe, world leaders have used the concept that ‘the people must always be ready for war’ to cover internal problems.

Today, Azerbaijan still uses the same method it has for the past 33 years. Even when there is no active fighting, the government ensures society still feels like the country is living in wartime, keeping people under pressure and helping sweep internal problems under the carpet.

If Azerbaijan really wants peace, it must ensure peace is something people feel in their daily lives. Instead of hate speech, there should be talk of coexistence and mutual neighbourhoods. Without this change, peace talk will remain a performance — words for foreign audiences, not a reality at home.

The contradiction between Azerbaijan’s peace rhetoric abroad and its war rhetoric at home turns the peace process into an image project, not a real political will. True peace will only come when public opinion changes, when the language of hate stops, and when people can finally feel peace in their everyday lives.

This article was translated into Russian and republished by our partner Jnews.