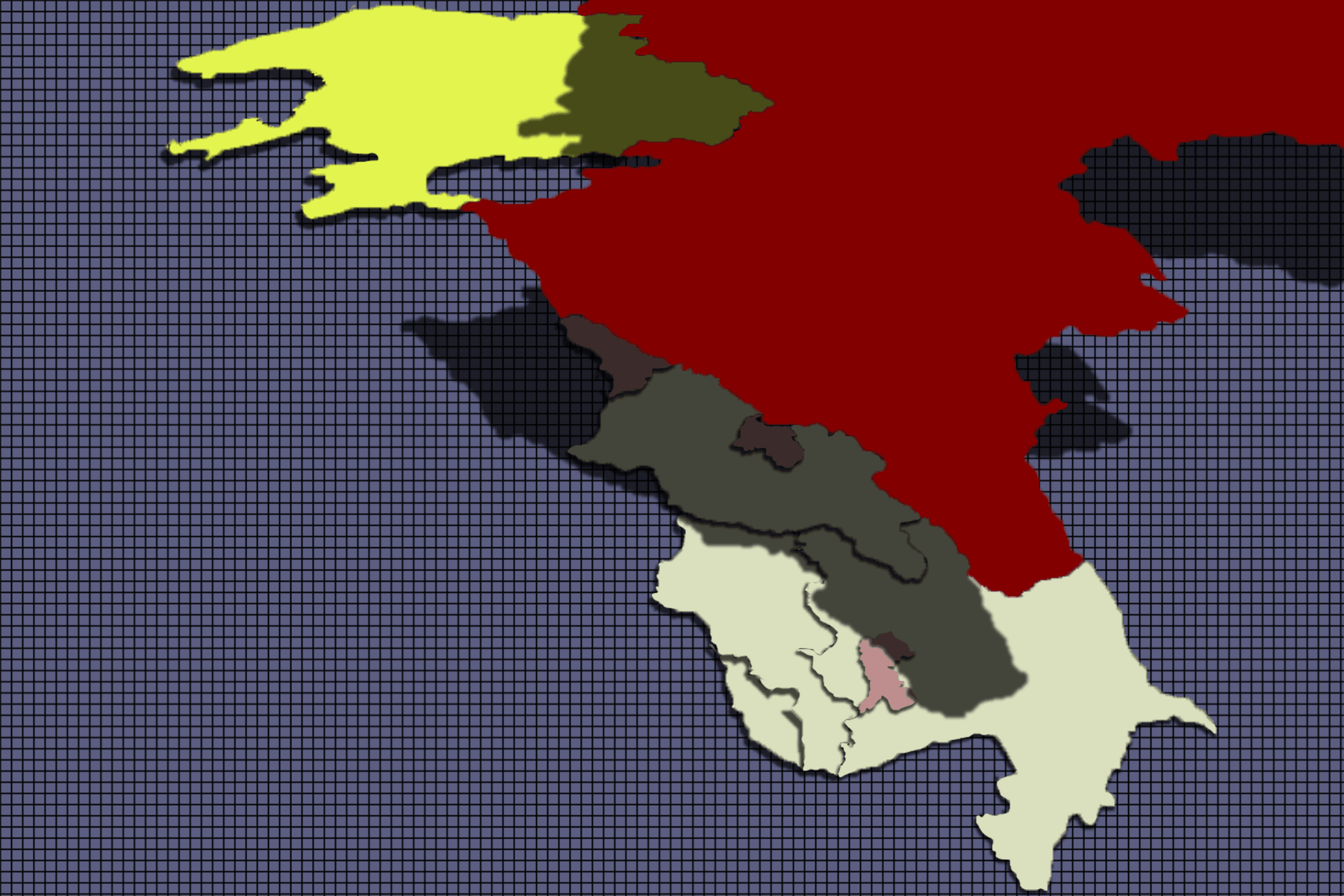

The invasion of Ukraine could see an isolated and resurgent Russia in the South Caucasus, which has troubling implications for the sovereignty of Armenia and the security of Nagorno Karabakh.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine completely changed the entire dynamic of Russo-Western relations in a matter of days. By launching its large-scale offensive against Ukraine, Moscow crossed a red line, becoming the target of unprecedented Western sanctions. The collective West has now adopted a policy of total isolation and exclusion towards Russia.

Moscow’s revisionist actions along with major policy shifts in Western capitals will undoubtedly have serious implications for the entire South Caucasus and for Armenia in particular. Regardless of the outcome of the war, the world and the region will not be the same again.

The delegitimisation of the Minsk group and Russian peacekeepers

The trend will have particularly significant repercussions for the mediation process of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The OSCE Minsk Group is the only internationally mandated format for mediating the conflict. However, it has been greatly marginalised in the aftermath of the 2020 Second Nagorno-Karabakh War due to the increased Russian role and Azerbaijan’s reluctance to carry on with the format.

For many years, the Minsk Group (co-chaired by the US, France, and Russia) has been one of the few venues where Russia and the West have cooperated and not confronted each other. This no longer seems to be the case.

The Russo-Ukrainian war could be the last nail in the coffin of the Minsk Group. The West’s new policy of total isolation of Russia as well as Moscow’s aspirations to tighten its grip on the South Caucasus won’t leave much space for the existence of such relics of the post-Cold War world order.

Another serious implication of the Russian invasion of Ukraine could be the gradual marginalisation and delegitimisation of the Russian peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh. Several thousand Russian troops were deployed to the conflict zone as part of the agreement brokered by Russia to put an end to the 2020 war.

The attitude of key Western actors towards the peacekeeping force had been quite constructive before the invasion of Ukraine. There had been a clear understanding in the West that the presence of the Russian peacekeepers plays a positive and stabilising role in the conflict.

However, in light of the invasion, this approach might change. It is no accident that since the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian war, Azerbaijani state-affiliated media outlets and pro-government experts have been spreading baseless claims about the alleged deployment of some Russian troops from Nagorno-Karabakh to Ukraine.

For Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, this is an issue of existential importance. Without the presence of a permanent peacekeeping force in the conflict zone, Nagorno-Karabakh will face a grim prospect of ethnic cleansing and there seem to be no realistic alternatives to the Russian peacekeeping mission at present.

An ever more difficult balancing act

One of the biggest implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the South Caucasus will be to further decrease Western influence in the region.

Russia and Turkey will most likely continue their pragmatic interaction with the South Caucasus, aiming to minimise the role of outside actors. This process started after the end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War with the creation of the 3+3/3+2 format (Russia, Turkey, Iran, Azerbaijan, Armenia and possibly Georgia) and will only intensify in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine.

The Russo-Western confrontation will also substantially shrink Armenia’s room for manoeuvre in foreign policy issues.

The war is not over yet, but the first signs of this trend are already visible. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the Armenian leadership has been exerting maximum efforts to preserve neutrality. Officials in Yerevan have attempted to keep a low profile and have called for a diplomatic solution to the conflict.

Armenia abstained in the UN General Assembly on a resolution condemning the Russian invasion. Yerevan has also been reluctant to recognise the independence of the self-proclaimed People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Yerevan’s neutral stance has noticeably irritated the Kremlin. On 4 March, two days after the afore-mentioned UN General Assembly vote, a phone call took place between the foreign ministers of Russia and Armenia — Sergey Lavrov and Ararat Mirzoyan. The official readout of the call published by the Russian MFA said that the ministers, among other things, discussed the issue of ‘coordinating approaches’ in the international arena. It is pretty obvious that Moscow was upset with Yerevan’s abstention in the UN and used this call to reproach its junior partner. After the end of hostilities in Ukraine, Russian pressure on Armenia will surely increase.

Moreover, there is a significant risk that in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine, Russia will try to integrate Armenia into its union state with Belarus, aiming to solidify its hold on Yerevan. Moscow has been trying to push the agenda of the union state in Armenia since the end of the 44-day war in Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia will most likely become more persistent after the war in Ukraine, instrumentalising its allies within Armenia in this process.

It is also evident that the invasion of Ukraine will move Russia towards further authoritarianism. The ‘Fortress Russia’ model is not supposed to tolerate any dissent within the country. The last remnants of the country’s civil society, free media, and political activism will be suppressed in the near future. This drift towards greater authoritarianism within Russia might affect Armenia’s domestic politics as well.

In recent years, the Kremlin’s approach towards domestic developments in Armenia has been quite pragmatic. It tolerated democratic changes in the country as long as they did not affect Yerevan’s foreign policy vector. For instance, Moscow issued neutral and balanced statements both during the 2018 Velvet Revolution and the failed quasi-coup attempt by the Armenian military’s top brass in 2021.

After the end of the Russo-Ukrainian war, Moscow’s interference in Armenia’s domestic politics may well grow. The enhanced siege mentality in Moscow could reinvigorate the Kremlin’s desire to have greater control over the domestic processes in countries like Armenia.

Thus, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has significantly complicated Armenia’s precarious geopolitical situation. Yerevan’s balancing act between Russia and the West will become even more difficult over time.

Moreover, Armenia will be facing a tough challenge in resisting Russia’s expansionist agenda.

Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine, alongside the drastic deterioration in Russo-Western relations, have already jeopardised the fragile peace in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone and will cause more uncertainties in the future.

It will take enormous efforts from the decision-makers in Yerevan to preserve Armenia’s sovereignty and safeguard Nagorno-Karabakh’s security in this new period of geopolitical turbulence.

[Read more: Silent and uneasy: Armenia’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine]

The opinions expressed and place names and terminology used in this article are the words of the author alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.