Thousands of protesters took to the streets in both Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia’s capitals on Tuesday evening, demanding international intervention and support, as the Red Cross warned of a humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Protesters demanded action to support the blockaded region, which is facing critical shortages of staple goods.

Shortly before the protest, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan held a press conference discussing the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh and defending his government’s actions.

The region has been under complete blockade since mid-June, when Azerbaijan banned Russian peacekeepers from delivering humanitarian aid to Nagorno-Karabakh. The blockade of the Lachin Corridor, the sole road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, has been ongoing for over six months, after first being blocked by Azerbaijani protesters in December 2022.

Since then, both the local government and international humanitarian organisations have warned that people in the region are facing a humanitarian crisis as a result of severe shortages of staple foods, medicine, and fuel.

The rallies were called by the authorities in Stepanakert. No Armenian political forces publicly organised or joined the protests, which in Yerevan were organised by people from Nagorno-Karabakh. Speeches in Yerevan and Stepanakert were broadcast live at both protests.

[Listen to The Caucasus Digest: Podcast | Blockade fatigue in Nagorno-Karabakh]

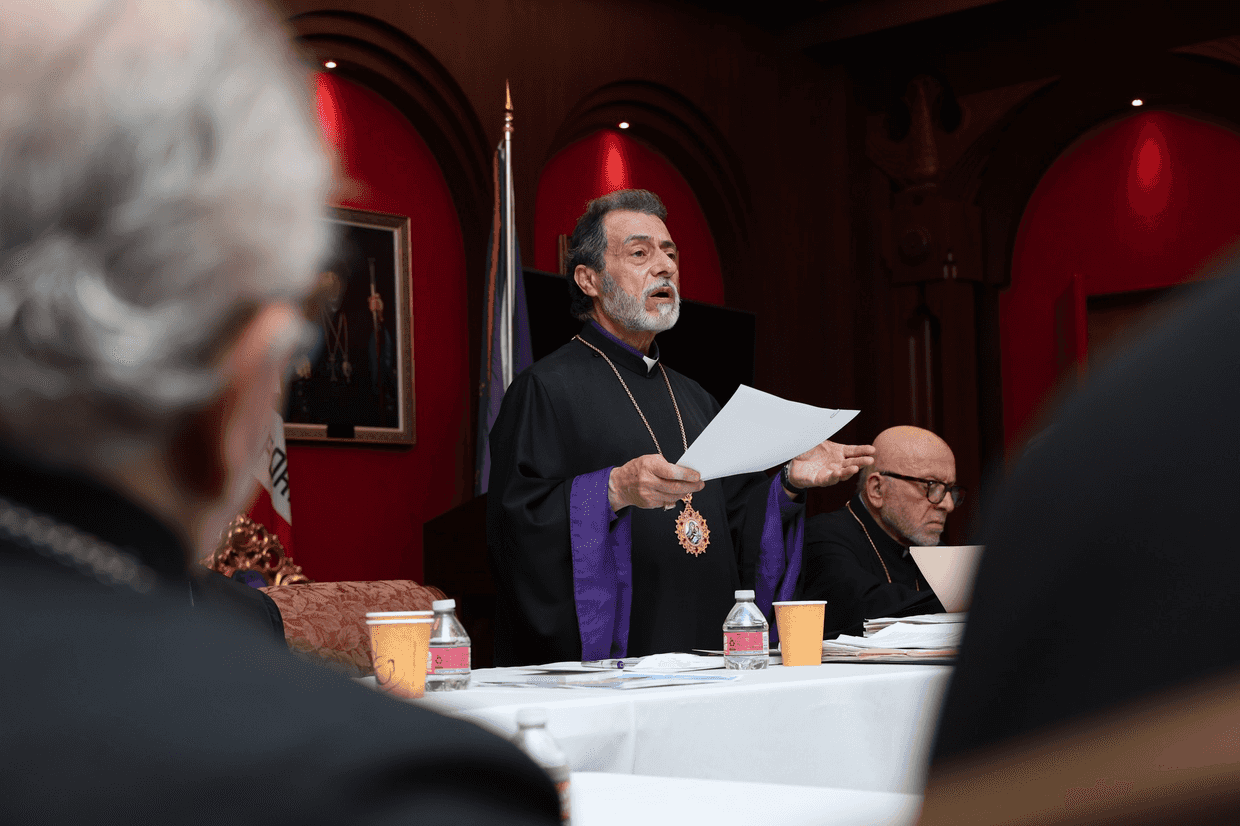

Speaking in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s State Minister Gurgen Nersisyan fiercely criticised the Armenian government for its decision to recognise Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, stating that any such ‘verbal or written’ assertions were unacceptable.

Armenia’s government and its Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan have repeatedly stated that Armenia is ready to recognise the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan, including Nagorno-Karabakh, if Azerbaijan agrees to recognise Armenia’s territorial integrity and leaves Armenian territories it occupied between May 2021 and September 2022.

The Pashinyan government’s decision to stop advocating for the right to self-determination of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian population after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War has deepened existing mistrust between the two governments, prompting authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh to frequently sharply criticise Pashinyan and his cabinet.

‘Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh] cannot be considered within the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan because it is a long-established political unit’, Nersisyan stated.

‘That approach is incapable of ensuring peace in the region and the safe existence of the people of Artsakh. Moreover, it cannot even guarantee the existence of Armenia because the Turkish–Azerbaijani tandem takes issue not with Artsakh but the entire Armenian people and the Armenian statehood’.

After the rallies concluded, protesters marched to the main military cemeteries in Yerevan and Stepanakert.

Attempts to deliver aid

In recent days, discussions of delivery of humanitarian aid have grown increasingly active, with Armenia promising to deliver aid on Wednesday, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) stating publicly on Tuesday that it was unable to deliver aid to Nagorno-Karabakh ‘despite persistent efforts’.

These efforts reportedly included attempts to use routes entering the region from Azerbaijan. Azerbaijani officials have repeatedly suggested that aid could be delivered to Nagorno-Karabakh via Aghdam, a town that came under Azerbaijani control after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

[Read more: Backlash in Armenia as EU backs Nagorno-Karabakh aid via Azerbaijan]

A convoy of approximately 400 tonnes of food and medicines left Yerevan for Stepanakert early on Wednesday morning.

Armenia’s Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs stated that the aid consisted of only the most essential goods, including sugar, oil, flour, pasta, salt, milk powder, baby food, and medicines, and would be sufficient only for one or two days. At the time of publication, the convoy was still in transit.

While officials in Yerevan and Stepanakert stated their expectation that Russian peacekeepers would accompany the cargo through the Lachin checkpoint to Stepanakert, no information was provided on whether this was agreed with the Russian forces.

Azerbaijan’s State Border Service called the decision to send the aid convoy to the entrance of the Lachin Corridor a ‘provocation’, and warned Armenia against ‘aggravating the situation’.

A humanitarian crisis has been growing in Nagorno-Karabakh since the Lachin Corridor was first blocked by alleged eco-activists associated with the Azerbaijani government in December, with the region immediately losing over 90% of its daily supply of food and other essential goods from Armenia.

Since then, only Russian peacekeeping and ICRC vehicles were allowed to pass along the corridor, delivering essential goods and transferring patients to and from Armenian hospitals.

Existing shortages of food and medicine have significantly worsened since mid-June, when the transfer of humanitarian aid by Russian peacekeepers was banned after a clash between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces. ICRC vehicles were limited to transporting patients, but barred from delivering any goods to the region.

ICRC access has since been fully banned twice, and both times restored following a meeting between the country’s foreign minister and the head of the ICRC in Azerbaijan. In the second case, Azerbaijan accused ICRC drivers of attempting to ‘smuggle’ cigarettes, mobile phones, and fuel into the region.

In its public statement on Tuesday, the ICRC called for ‘the relevant decision makers’ to allow the organisation to resume its humanitarian work in the region, and called on both Armenia and Azerbaijan to reach a ‘humanitarian consensus’.

‘ICRC is not currently able to bring humanitarian assistance to the civilian population through the Lachin corridor or through any other routes, including Aghdam’, the statement read.

It noted that the civilian population was facing a lack of life-saving medication, as well as staple goods including hygiene products, baby formula, and food.

‘Fruits, vegetables, and bread are increasingly scarce and costly, while some other food items such as dairy products, sunflower oil, cereal, fish, and chicken are not available’, the statement added. ‘The last time the ICRC was allowed to bring medical items and essential food items into the area was several weeks ago.’

It stated that people with diseases, elderly people, and children were particularly at risk.

‘This is life-saving work, and it must be allowed to continue’, the statement concluded.

Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry swiftly responded to the statement, asserting that Azerbaijan had offered to deliver humanitarian assistance, but that ‘the Armenian side’ had refused both offers of humanitarian aid and the entry of an ICRC doctor via roads from Azerbaijan.

The statement additionally warns that the Red Cross should observe its humanitarian mandate, and not abuse it ‘for political purposes’.

Journalists and local authorities have reported severe fuel shortages, leaving ambulances and public transport immobilised, which have combined with food and medicine shortages to drive increases in mortality.

Pashinyan: ‘Are we a traitorous government?’

Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan held a five-hour press conference hours before the rally began, focused on the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict and humanitarian situation in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Pashinyan appeared to react emotionally to the questions of opposition journalists, and recorded questions from residents of Nagorno-Karabakh, including one asking him whether he considered himself to be a ‘traitor and a failed politician’.

Pashinyan noted the financial and material support that his government had sent to Nagorno-Karabakh since the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

‘[If we are] a traitorous government, give up the support of the traitorous government’, he said. ‘What is a person who receives money from a traitor?’

He went on to accuse journalists of being part of a ‘political campaign’ and being ‘instructed’ to distribute propaganda, after being asked about pictures his wife, Anna Hakobyan, had shared on social media last week, showing fruits and vegetables grown in their family garden. The post was criticised by Armenian-language social media users, who accused Hakobyan of being insensitive towards people on the verge of starvation.

Pashinyan added that while the question of delivering aid from Azerbaijan to Nagorno-Karabakh had been discussed in a meeting between him, Azerbaijani President Aliyev, and EU Council President Charles Michel on 15 July, Armenia did not have a ‘mandate’ to discuss the matter.

‘I have a mandate to discuss the issue related to the Lachin Corridor, because the Lachin Corridor was created by the tripartite declaration of November 9, 2020, of which I am one of the signatories’, stated Pashinyan. ‘At those platforms, we discuss only the issues related to the illegal blocking of the Lachin Corridor and the opening of the Lachin Corridor, I do not discuss other issues’.

Pashinyan struck a different tone in an article about the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh published by French media outlet Le Monde on Monday. Pashinyan described the blockade as a ‘Sarajevo-style siege’, and called for ‘Europe and partners around the world’ to take action.

‘The authorities in Baku use force, and the threat of further military escalation, to achieve their irredentist aims. This should not be tolerated; the consistent torpedoing of the peace process must have consequences’, wrote Pashinyan.

Following a meeting between Armenia and Azerbaijan’s foreign ministers in Moscow on 25 July, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that the talks had proven ‘fruitful’.

He added that Yerevan had ‘[understood] the need to convince Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to meet as soon as possible with Azerbaijani representatives’, to discuss their rights in relation to relevant legislation and international obligations.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.