★★★★☆

Famed Azerbaijani screenwriter Rustam Ibragimbekov’s 1996 novel captures the story of Soviet Baku across multiple generations.

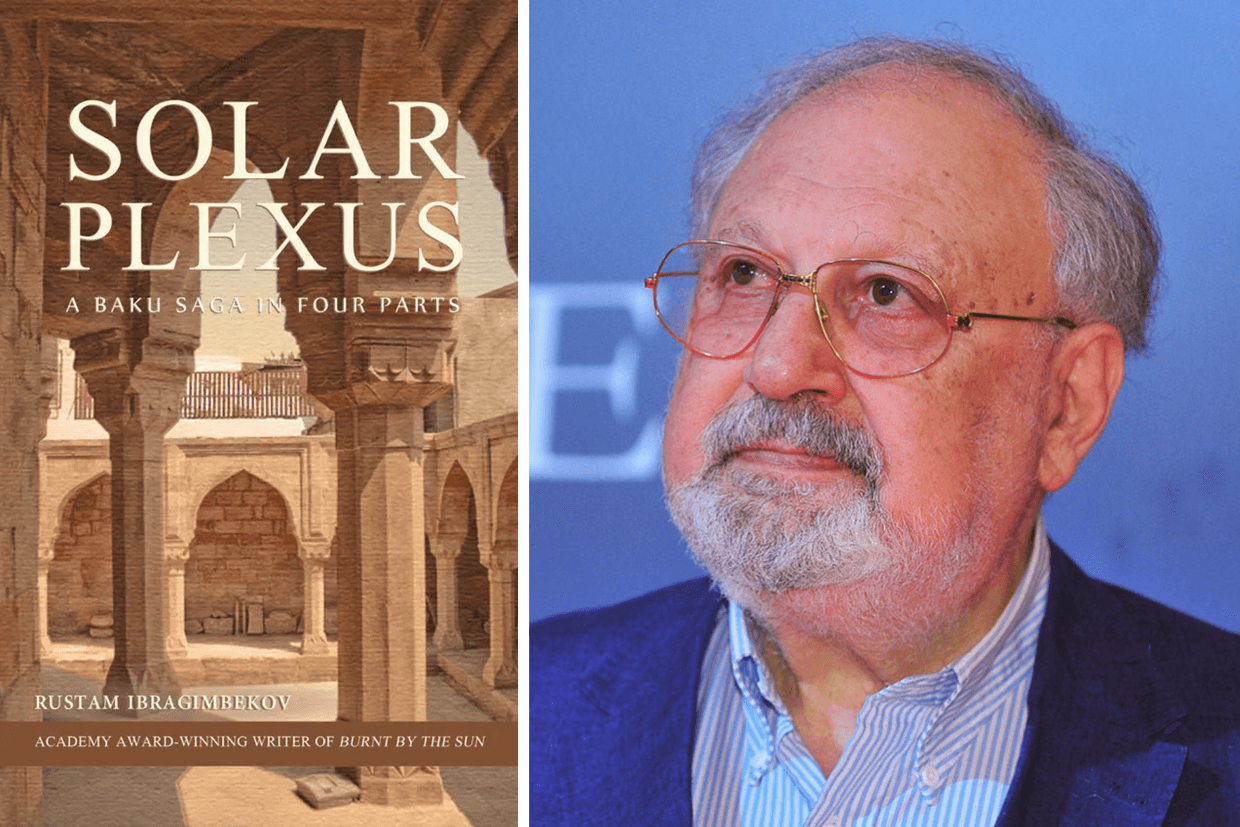

Azerbaijani writer Rustam Ibragimbekov is best known for his screenplays, of which he wrote more than 40, including for the 1994 Oscar-winning film Burnt by the Sun. In Azerbaijan, he was also noted for his literary prose — yet the majority of such works have not been translated into English.

Andrew Bromfield’s 2014 translation of Ibragimbekov’s 1996 novel Solar Plexus: A Baku Saga in Four Parts from the original Russian for Glagoslav Publications marks a notable exception.

As the title suggests, Solar Plexus centres around the stories of four Baku residents, spanning across three generations and stretching from the post-Second World War II era to the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. Though distinct narratives in their own right, each of the four stories are interconnected to weave a full story of five young friends once all originally from a traditional courtyard house in the city suburbs.

The novel opens with Alik, a young Russian man navigating his relationships with his sister’s Azerbaijani husband Nadir and their neighbour Fariz and his family, who, while once close friends, broke off relations upon rising in Soviet society.

The second section follows Marat, a close friend of Alik’s nephew Lucky, as he becomes the last resident to have remained in the traditional house while working in Baku’s booming petroleum industry.

Ibragimbekov next focuses on Fariz, following him in his later years, having become the impressive rector of Baku’s scientific research institute. Despite his placement within the city’s social hierarchy, flashbacks show the cost of this rise to prominence, including the strained relations he continues to have with his eldest son Eldar.

The book concludes with a short chapter set in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union when all five friends, including Alik, Marat, and Eldar, find themselves in trouble with the new militia after a brawl leads to the death of one refugee from Armenia.

Throughout all four narratives, Ibragimbekov touches upon a number of deeper topics, such as the various perspectives towards Russian immigrants in Baku over the decades, as well as the constant reconstruction of the city itself due to its oil money — topics very much still affecting the city today.

Ibragimbekov also does not shy away from critiquing the post-Soviet transition period. In the final section, the doctor turned screenwriter Seidzade — a seeming prototype of the author himself — reflects on how while in the Soviet period you had to ‘swallow plenty of insults and humiliations’ to get published, there was still a sense of equality.

‘At least in those days you were dealing with the state: your application was made to the state, your resentment was directed against the state, and your conflict was with the state when you refused to surrender and carried on doing things the way that you thought was right. But now the state no longer had any interest in you, it had given you a freedom that you had to pay for with far greater humiliations than before: now your fate was decided by “men with money” and unfortunately rich men are not the best part of humanity’.

While Ibragimbekov successfully tackles a number of these larger themes and questions within the novel, one notable critique lies in his treatment towards women. Though Ibragimbekov initiates a discussion of the effects of Soviet modernisation on the rights and opportunities of women, the majority of his female characters lie flat on the page, simply there as the wives, mistresses, and playthings of the men that surround them. There is little support between women either, with an almost constant sense of competition between them whether to gain the attention of a man or to promote their already secured male partners through sexual encounters and threats.

Despite this, Solar Plexus generally works as an interesting exploration of Baku life in the Soviet period, giving readers a strong understanding of a variety of perspectives operating at that time, and influencing the period that followed. This is especially valuable given the general dearth of Azerbaijani literature in English.

Book details: Solar Plexus: A Baku Saga in Four Parts by Rustam Ibragimbekov, 1996, translated into English by Andrew Bromfield in 2014 for Glagoslav Publications. Buy it from the publisher here.