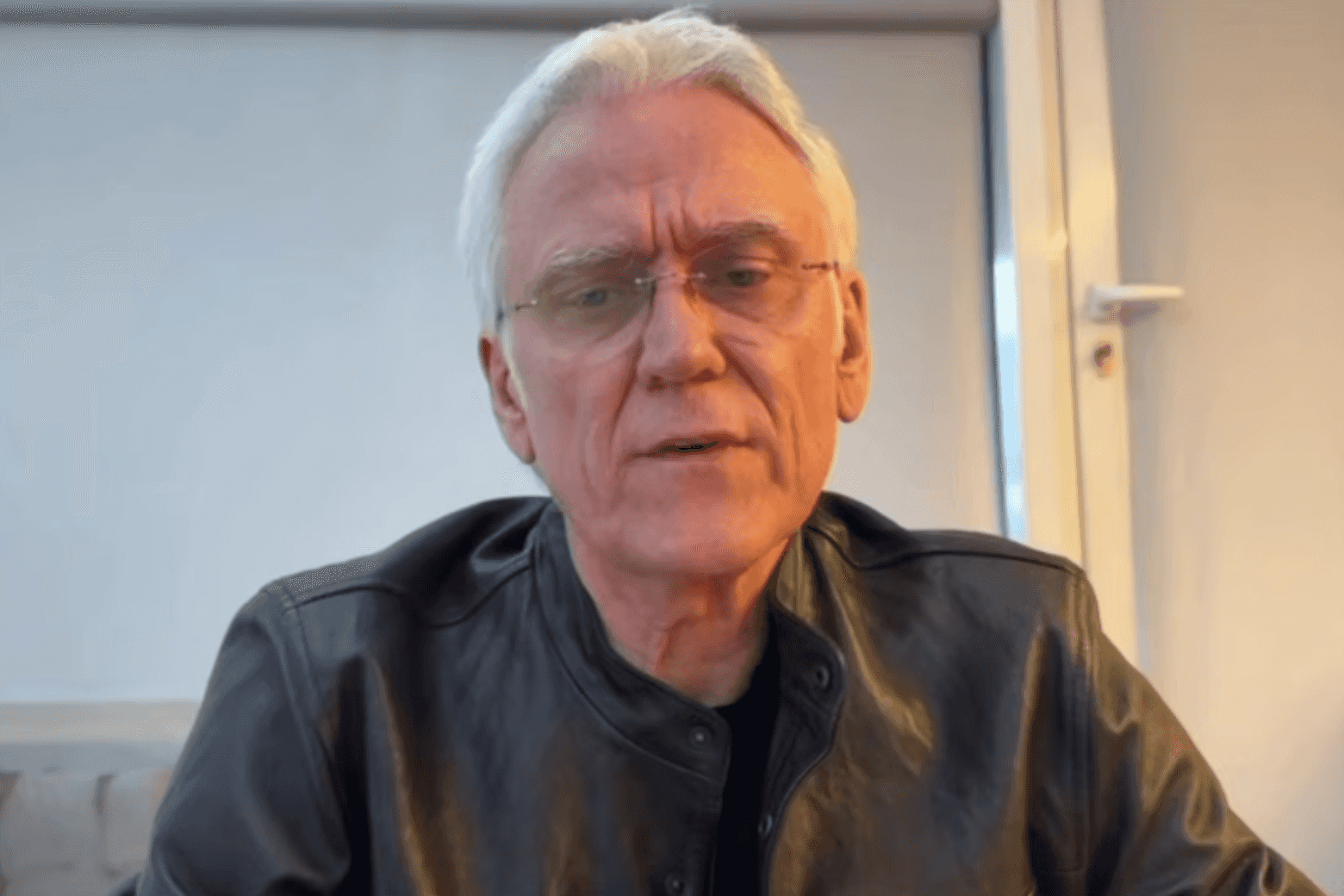

‘Who is the Sukhumian boy?’, ask Georgian artists Tamada (Lasha Chkhapelia/Chapel) and DillaNext (Zura Jishkariani, known for Kung Fu Junkie and KayaKata) in their new song and music video — ‘Sokhumeli Bichi’, meaning Sukhumian boy.

For them, this boy is more than a single person — he embodies the unspoken identity of Georgian IDPs from Abkhazia, including themselves, who fled following the 1992–1993 War in Abkhazia.

The displacement left deep wounds and little contact across the divide.

‘When we left, we were Georgians, but then in Georgia, we were Georgians from Abkhazia’, Dilla recalls. Their culture, he says, is distinctive from other Georgians. ‘Sukhumians [in Tbilisi] say that Sukhumians are their own nation. Thousands grow up in this culture, yet there is no representation. Not musically, in literature, or otherwise’.

Both musicians fled as children along with approximately 250,000 others — Tamada as a toddler, Dilla at seven. They arrived in Tbilisi amid civil unrest, hyperinflation, power blackouts, and rising crime.

Roughly half of Abkhazian IDPs lived in makeshift shelters — repurposed hotels, sanatoria, schools — while the rest stayed with relatives or rented flats.

In 1990s Tbilisi, when paramilitary groups and neighbourhood thugs dominated the streets, local identities were closely tied to the neighbourhood one came from. As a boy, being stopped and asked ‘Which district are you from?’ was a dangerous ritual.

‘My parents rented flats and we moved a lot, so I never had a district’, Dilla says. ‘I had to identify as Sukhumian — and it actually worked’.

‘If you gave the wrong district, you could get beaten up. But if you said Sukhumi, people would say, “Respect, bro”, and leave you alone’, Dilla says.

‘Or like, “Leave him alone, he’s from Sukhumi” ’, Tamada adds.

‘A virtual address, a virtual home’

‘Sukhumi is like a virtual address, a virtual home’, Dilla says. ‘You say you are from Sukhumi, but you do not have a physical city. You act Sukhumian, but in another city […] It’s like carrying a city inside of you […] it’s a very strange identity’.

Both musicians stress that the Sukhumi they know stems from what was told to them by their parents.

‘We have not experienced it, we can’t touch it, we can only imagine it’, Tamada says.

At the same time, he explains how being Sukhumian also comes with a sense of responsibility.

‘From a very young age, you’re told you must get it back. While your imagination is still forming, you have to imagine the uncle you never knew who was killed at 21, you wonder what your neighbour who stepped on a landmine looked like, your father who [almost] blew up […] I grew up on my father’s battlefield stories’, he says.

Yet, being Sukhumian, they explain, is less about geography, and more about a code, ‘a code of simple humanism, acting correctly, a language embedded in urban flavour’ that thousands of families carried with them while fleeing Abkhazia.

The imaginary comes from a multi-cultural Sukhumi, which existed in its ‘golden age’ from the 1950s–1980s, when, despite broader Soviet tensions, the city maintained a shared urban culture between Georgians, Russians, Abkhazians, Armenians, and even Greeks.

‘My father used to explain to me that from a taxi driver to a university lecturer, everyone understood the context of the city. People were loyal to each other’, Dilla says.

Related to this multiculturality is the importance of language, which is also used in the song.

‘Sukhumian slang is very unique. There is a bit of Russian criminal lexicon, mixed with Abkhaz words and Mingrelian sayings’, Dilla says.

‘Even intonation is very different’, Tamada adds.

Sukhumi is remembered as ‘gorod bez fraerov’ (city without suckers) which is how the song ends. The term ‘fraer’ is deeply embedded in their, and wider Soviet criminal slang.

‘A fraer is someone who fails in the street code as well as basic human ethics […] someone who just doesn’t get it, who would bump into you and not apologise’, Dilla explains.

‘As a kid, whenever there was laughter at the table in my house, some Sukhumian would say “Gorod Bez Fraerov” and everyone would laugh’, Tamada recalls.

Some might be tempted to read the phrase as a jab at Abkhazians. However, ‘gorod bez fraerov’ was also spoken among Abkhazians with the same affection.

The song lyrics carry another quiet Sukhumian moral code: lay no blame, a phrase Tamada repeats,

‘We Sukhumian people are not like that. […] pointing fingers at others changes nothing. Blame is a poetic thing: if you cast it on someone else, it holds you back’, he says.

‘It’s also part of Sukhumian code not to annoy anyone, not to irritate anyone’, Says Dilla. ‘If anything “reconciles” us with Abkhazians, it will be Sukhumian politeness’, Tamada adds.

Negotiating identities

The duo explain that Sukhumians who grew up in Tbilisi experience a different phenomenon. For their parents, speaking of Sukhumi is to speak of a blossoming city, ‘where if you ask today, everyone owned and lost something big’. But this was different from the reality they faced.

‘This is when you start reading your fate on cracked asphalt,’ as they put it in their new song.

‘I do remember once during a quarrel with my father, he told me “Sukhumians do not act that way” ’, Dilla recalls. ‘Then he told me I am only 50% Sukhumian and I was really pissed off’.

Both musicians remember switching between identities in and outside of the house, and negotiating how to present themselves in new social environments.

In Dilla’s home, they spoke Russian and Mingrelian; Tamada’s household spoke Russian, Mingrelian, and Georgian. For Dilla, small moments — like a knock at the door and his parents saying ‘It’s Georgians’ — marked the boundaries: Georgian meant someone who was neither Mingrelian nor Abkhazian.

‘There was a cultural difference inside’, Dilla reflects. ‘Perhaps it came from living alongside Abkhazians and noticing how they saw us as others. Gradually, you develop that mentality yourself’.

Tamada recalls that the Sukhumi he grew up with was about resilience and empathy.

‘You learn a certain kind of empathy — the kind I see among Mingrelian, Sukhumians, and Abkhazians living in Abkhazia’, he says.

‘It makes adaptation harder, but it also creates a warmth inside the culture. The fact that warmth comes from trauma is important’, Dilla adds.

Yet trauma has left its mark.

‘There are individuals among the displaced who have become ultra-nationalist, and some who cannot forgive the killings of their family members’, Dilla explains.

Resentment lingers in different ways, sometimes fading over decades. But what endures most, the musicians say, is the loss of being uprooted from the most fundamental things: home, identity, family.

‘Yet the topic is so dangerous that you could suddenly slip into pathos, or aggression, or victimhood, that I lost the city. But Sukhumian identity exists beyond all of that’, Dilla says.

Who is the Sukhumi boy?

The collaboration, the artists insist, is about making IDP culture visible.

‘Bringing that into the open feels risky, but necessary’, Dilla explains.

Today, they argue, the culture of the displaced is mostly ignored by politicians and the wider public. When it is acknowledged, it is usually either wrapped in nationalist rhetoric or reduced to tragedy — like the several cases of IDPs setting themselves on fire in protest over decades of unsolved housing problems.

‘The positive field [of culture] has been replaced by pity and fakery’, Dilla says.

‘Ask any IDP what annoys them’, he continues. ‘You’ve lost everything, and then someone writes a nationalistic, pathetic song about your life — using it for money, politics, propaganda. They make it look like IDPs are saying these things, but we are not’.

The Sukhumi boy they know is different.

‘He doesn’t just cry’, Dilla says. ‘He carries the trauma, the cracks, but channels them into the world, into art. And we share that with each other’.

For years, being Sukhumian was portrayed negatively, Dilla explains.

‘There’s a phase of shame, when you absorb other people’s judgments’, Tamada says.

‘What we’re doing is shifting it back — taking it out of the negative field and into a positive one’, Dilla says. ‘Translating it into sound and words that you consider a real art’.

The song is built on these ideas. The Black Sea runs like a rhythm; bits of the song hit like waves. As the lyrics pulse — ‘Black Sea in the veins, Black Sea in the heart, Black Sea, on the black night don’t erase the trace’ — the sea becomes more than a backdrop.

‘The sea is like my DNA’, Dilla says, noting that it evokes both the city they lost and the continuity of Sukhumian culture they carry.

‘With this song, we wanted to show that you are also a Sukhumian boy, it’s part of your identity, part of your puzzle, and you are proud of it’, he says.

That shift, Dilla explains, can be liberating: ‘Younger people have told me they were ashamed and hiding being displaced. They said they saw my blogs and saw that people liked it, they also started embracing being Sukhumian as part of their identity. When people see someone use it without shame, it frees them. I hope this song will have the same effect’.

‘We want the world to know the Sukhumian boy exists’, he continues. ‘Sukhumi boys are here, they survived — and many of them are doing incredible things’.

‘But this song isn’t only about IDPs’, Tamada adds. ‘It’s about the Sukhumi boy in Georgia, in exile elsewhere, even in Sukhumi today’, a concept made clear from the start of the interview, with Tamada noting that even his grandmother, Neli Kakashvili, is a Sukhumi boy.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.