The final nail in the coffin for human rights lawyers in Azerbaijan?

New amendments to the law on advocacy threaten to remove any last vestiges of independence within Azerbaijan’s Bar Association.

When police began arresting the last remaining staff working with Meydan TV within Azerbaijan in December 2024, few believed they would receive a fair trial.

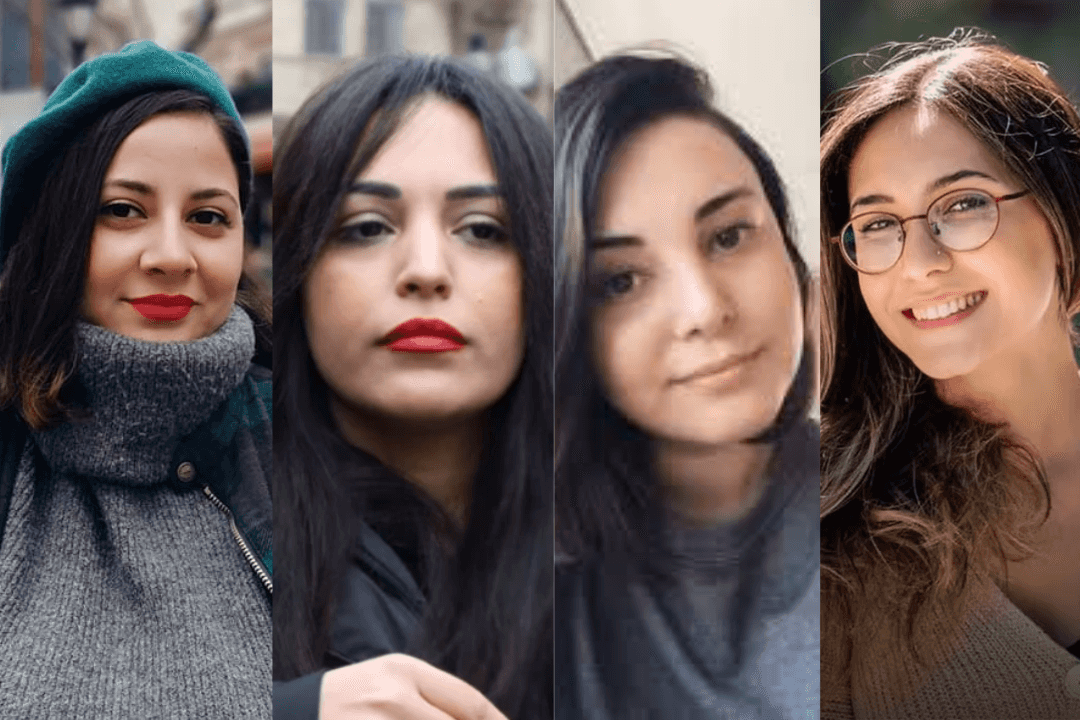

The six detainees — editor-in-chief Aynur Gambarova (Elgunash) and five journalists — were charged with money laundering, a charge levied against other independent journalists in the country after the authorities launched a renewed crackdown on the press a year earlier. Six others who worked with Meydan TV have also since been arrested as part of the case.

While expectations for justice were low, even putting forward a defence proved difficult.

Speaking to OC Media from exile in Germany, where Meydan TV is headquartered, Orkhan Mammad, an editor at the outlet, said they struggled to find lawyers even willing to take on their case.

This, he said, was because few lawyers free from government influence remain active in the country.

‘Another problem is that accusations against lawyers are aired on state television […] and they are also openly attacked or even targeted’, Mammad added.

For over a decade, pressure has increased on lawyers — through supposedly independent disciplinary hearings — not to put forward cases questioning the authorities.

On 10 October, the Azerbaijani Parliament began discussing new amendments to the law on advocacy and related activity — amendments that critics warn could spell the final nail in the coffin for legal advocacy in Azerbaijan.

The state capture of the Azerbaijani Bar Association

Only two days before the discussions of the amendments in parliament, the Bar Association announced they had taken new disciplinary measures against several lawyers.

The Bar Association was originally created as an independent, self-governing organisation for lawyers to regulate the profession, as well as provide professional support to its members. They cite their main objective as protecting ‘the rights and freedoms of every person, protected by law, to provide them with professional, high quality, honest legal assistance, and to enhance the prestige of the legal profession’. There are currently over 2,500 members.

‘Two lawyers were suspended from their work for a specified period, four lawyers were given warnings, and one lawyer was reprimanded for disciplinary violations’, the association’s official website wrote on 8 October.

The lawyers were not named by the Bar Association, however, RFE/RL identified them as Zabil Gahramanov and Ramil Rustamov, each of whom were suspended for six months.

Gahramanov is a well known figure in legal circles, having taken on high profile cases including that of Ilkin Suleymanov, who was accused of murdering 11-year-old Narmin Guliyeva in the northwestern Tovuz District. Gahramanov also helped Polad Ismailov appeal an 11-year sentence for murder, securing his release after serving four years.

Shortly after his suspension, Gahramanov was detained and remanded to three months of pre-trial detention on charges of hooliganism — a friend suggested to OC Media that the case could be connected to Gahramanov’s frequent public criticism of the police in Ganja.

This is not the first time lawyers have been punished for their public opinion in Azerbaijan — the Bar Association’s disciplinary commission has frequently applied these rules against independent lawyers. Indeed, these incidents have often been discussed on social media, with independent lawyers claiming that these rules serve only to silence them.

One member of the Bar Association who spoke to OC Media on condition of anonymity said the new changes in the legislation meant lawyers would be obligated to refrain from expressing critical opinions about government agencies and officials in the media and online.

‘Even if a lawyer encounters illegal actions in an institution, they [would be] obligated not to report it to the public, and if they disseminate such information, they [would be] obligated to immediately delete it’.

According to the lawyer, all this demonstrates that lawyers and the Bar Association lack independence.

‘The influence of the state or individuals close to the executive branch is clearly felt in the Bar Association’s governance and decision-making mechanisms. This seriously hampers lawyers’ ability to take an independent stance, especially in politically motivated cases’, the lawyer said.

Although cases of direct punishment of lawyers who handle politically-charged cases have decreased somewhat in recent years, the source told OC Media that this was most likely because lawyers who take those kinds of cases were being more careful — not because state repression had lessened.

‘In previous years, lawyers were more open in expressing critical opinions in court and in the media. It was during this period that a number of lawyers were punished for these bold statements — recall, for example, the cases of human rights lawyers Khalid Baghirov, Yalchin Imanov, and Elchin Namazov’, the lawyer said.

The leadership of the Bar Association has insisted that lawyers must refrain from expressing ‘unfounded’ criticism of government agencies or officials or face punishment.

During an interview with local media in July, the chair of the Bar Association, Anar Baghirov, complained that ‘some lawyers are bringing individual court cases to public discussion on social media, sometimes in an unethical manner’.

Baghirov added that they had only urged the lawyers to refrain from doing so for now, but promised ‘more serious measures’ would be taken in the future if they did not heed this warning.

Samad Rahimli, a human rights lawyer, who lives abroad, confirmed to OC Media that the Bar Association is not, de facto, an independent body.

Rahimli applied to become a member of the Bar Association in 2018, but was unable to pass the interview, which was the second step.

‘The government can subjectively exclude blacklisted lawyers from the list of lawyers during oral interviews, in the absence of objective evaluation standards’, he says.

Rahimli stated that another problem in the Bar Association concerns disciplinary liability. According to him the Disciplinary Commission is also not independent, and lawyers can be punished very easily.

‘Furthermore, since there are no independent courts in Azerbaijan, no action can be taken in the event of a violation of lawyers’ rights by a professional lawyers’ organisation. This is because the courts do not ensure this right. Obtaining a decision from the European Court [of Human Rights] takes years, and the Azerbaijani government does not implement these decisions’, Rahimli said.

A lawyer’s primary responsibility: protecting the rights of the state?

The new amendments first came to public attention after a post on social media warning of how restrictive they would be by Azerbaijani human rights lawyer Emin Abbasov. After learning of Rahimli’s rejection from the Bar Association in 2018, he decided not to bother applying, though this restricted him from representing people in Azerbaijan. Eventually, following the increased pressure on civil society, Abbasov left Azerbaijan to work abroad.

In his post on social media, Abbasov argued that the legal profession had already been so weakened in Azerbaijan that they were no longer even able to play a role in shaping new regulations affecting their interests, and were unable to fight back against the numerous problematic provisions in the latest legislative proposals.

The current legislation, he wrote, stated that: ‘the primary responsibilities of the advocacy profession are to protect the rights, freedoms, and legally protected interests of individuals and legal entities, as well as to provide them with qualified legal assistance’.

He noted that the amendments would add the words: ‘as well as state bodies’, after the word ‘individuals’.

While the draft legislation was originally published on the parliamentary website, since Abbasov’s comments, it appears to have been deleted.

According to Abbasov, these new amendments mean the end of lawyers being able to take cases on behalf of civil society members or opposition politicians dealing with politically motivated cases.

Now, he argued, the legal advocacy profession would in all their work also be tasked with protecting the rights and interests of the state.

Azerbaijan’s Parliament will discuss the third draft of the amendments on 31 October, possibly going into force the same day.

Beyond the changes already mentioned, the two-term limit on the position of chair of the Bar Association will also be removed. In practice, this will likely mean that Baghirov will be able to remain as chair, presiding over what appears to be a plan to fully dismantle the independence of Azerbaijan’s human rights lawyers — perhaps the final nail in the coffin of Azerbaijani human rights advocacy.