Tamar Mearakishvili is an ethnic-Georgian activist and journalist in South Ossetia. Since her arrest in 2017 for ‘defamation’, she has been locked in a legal battle with the authorities. Tamar reflects on her life in Akhalgori, her legal woes, and the reaction of the Georgian Government to her case and others.

‘I was born in Akhalgori; my parents are from here as well. I finished school in Akhalgori, I was a very active child, I studied well.’

‘My class teacher gave the same evaluation to every student except me for graduation, and this was a big deal back then. Angry at me, she wrote that I had the skills of a leader and that I could organise my peers to do anything. Now it sounds good, but back then it was as if the militia had opened a probe into my case.’

‘As a child, I dreamt of becoming a voice actor for animated films, but there was no such faculty back then. Instead, I graduated from film studies at the theatrical university in Tbilisi.’

‘I started to work as soon as I started my studies. I used to work as a postwoman; I wanted to have my own income and would take all kinds of jobs.’

‘After I graduated, there was a job opening at the youth centre as the deputy head. In a few months, I became the director of the youth centre in Akhalgori. I became very popular.’

‘I was a director of the youth centre for sixteen years. I was fired twice by my Georgian employers, and once by the Ossetians.’

‘When I was fired from the youth centre I spent a year going to court hearings. After that, I stopped looking for a job here. I will never work with someone who persecuted me, I don’t plan to.’

‘They expected that as a woman — I would break’

‘Before my prosecution, I was part of several projects, I would travel to Tbilisi often for conferences and trainings.’

‘I was in Tbilisi right before the arrest. They selected that day because they wanted to see my personal documents. My daughter remembered that that day a car was parked at my house for several hours.’

‘When I came, they left the car and opened a notebook. They told me I was under arrest. It was a circus. They wanted to scare me. During the search, the person who was the most cheerful was me; I wanted to show them that I was not afraid, that I am strong.’

‘I told them I wanted to fix my hair. I told them in Georgian that my rights were being violated and demanded a lawyer, an interpreter, and that they read me my rights in Georgian. This made them angry.’

‘The search lasted for two hours. The person they instructed to film it had no connection to the militia or prosecutors; it was just some girl. When I asked for a copy of this footage they told me it had been deleted.

‘There were two investigators, one from the militia and one from the Prosecutor’s Office. I was in a dark room. There was one small lamp, which they would turn on and off.’

‘Probably a decision was made from above to punish me. Probably they thought that I wouldn’t be strong enough to go through this. They would underline the fact that I am a woman, that they managed to break men and I wouldn’t survive.’

‘I was completely alone. They didn’t let my mother or daughter visit me. They demanded I say who I was cooperating with; who I was. I was very firm and said that my mother language is Georgian and I had the right to use the services of an interpreter; that I didn’t understand what they were saying.’

‘One of them said I was lucky I was a woman, otherwise they would break my ankles and I would tell them everything. They expected that as a woman, I would break without physical pressure.’

‘My communication with them before I hired a lawyer was humiliating. They would ask me why I wasn’t married; who was feeding me; if I wanted a man; and why I was so “aggressive”. I would tell them these were not the right questions, and if they want to ask such questions they should at least protocol them.’

‘I would write everything on Facebook and speak with journalists. Then something unprecedented happened; an investigator in my case gave two interviews.’

‘It was unimaginable for an investigator to give a comment and respond to the Facebook posts of a civic activist. He said that they were indeed asking such questions, but that I misunderstood them, but the fact is, they admitted it’

‘They expected I would run away, that I wouldn’t be strong enough to fight, that it would be psychologically difficult for me, financially difficult too. A lawyer is expensive. Scheduled hearings would be postponed eight out of nine times. These eight postponed hearings cost me ₾5,000 ($1,700).’

‘Of course this was done on purpose and of course it was difficult for me — collecting money. It was very stressful when the case hearings were dragged on.’

‘They don’t know how to get out of this shame’

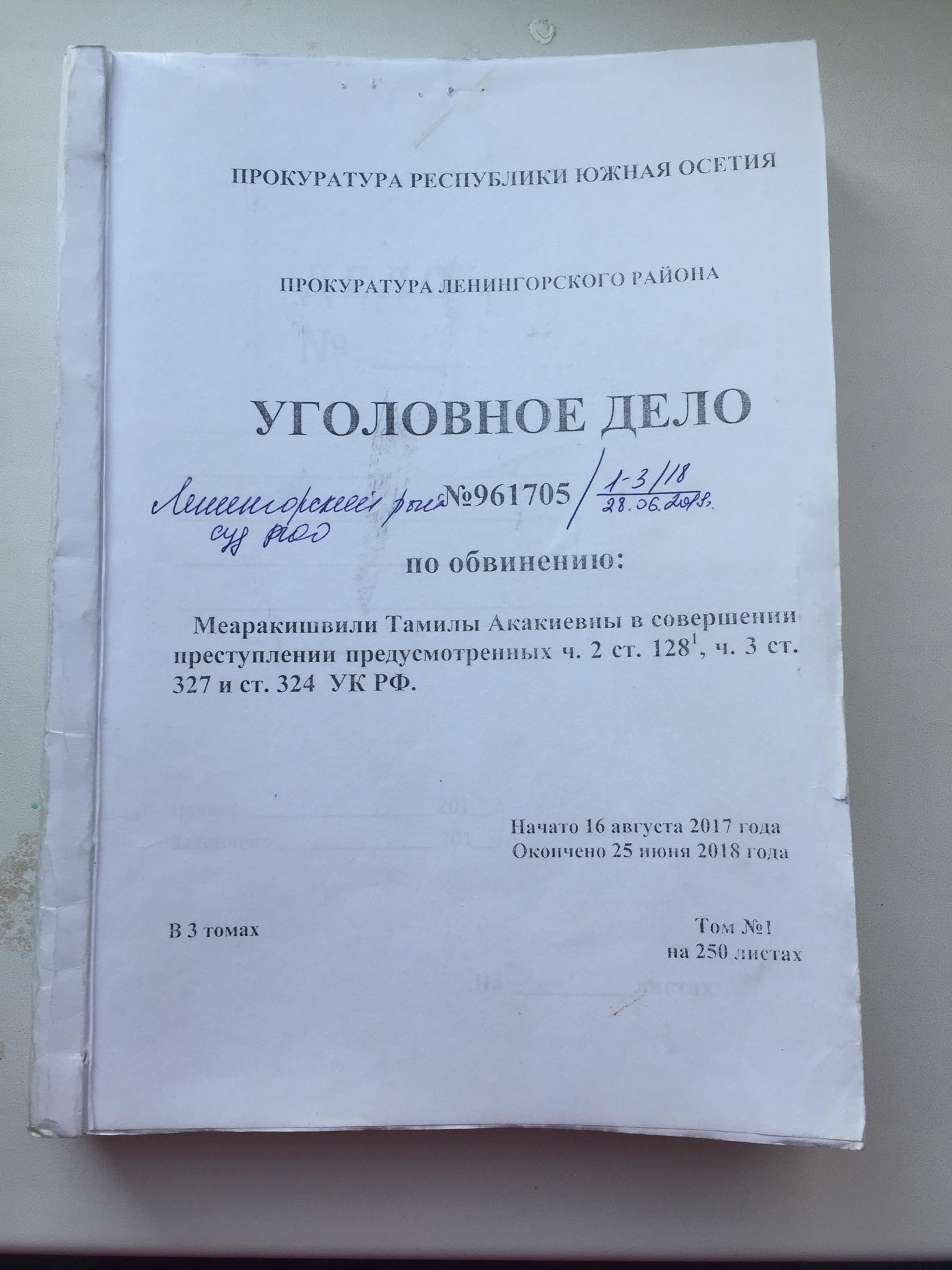

‘My fight proved that the rumours of my being a spy were a lie. The official reason for my arrest was defamation, but in reality, they were just looking for a reason to search my house.’

‘They were sure they would find a tunnel in my home. They took everything, all the cables, adaptors, everything. Now they don’t know what to do, how to get out of this shame.’

‘At one recent hearing, three out of four prosecution witnesses said they didn’t know what was written in their testimonies, but that they were asked to sign something they had not written. We were there, listening to them, there were MPs as well.’

‘Each time I went to Tskhinvali I would go to parliament, go from one room to another and ask MPs to attend my hearings. People were surprised, but I would tell them there was nothing surprising. MPs are elected by the people and they have responsibilities.’

‘My case consisted of enormous volumes of things that didn’t make any sense. For example, in one volume there was a law about Georgian citizenship passed during Eduard Shevardnadze’s [President of Georgia from 1995–2003] time with a Russian translation. I don’t know why they included it.’

‘There were testimonies of 30 witnesses, almost all the same as each other with only the personal details changed.’

‘There was also information about whether I am registered in a tuberculosis dispensary or not, again, no idea why they needed it.’

‘This and other idiotic documents are part of my case.

‘In a way, this was good, because a part of Ossetian society that didn’t support me two and a half years ago supports me now.’

‘Those days when I was alone [under house arrest], a week would pass and I wouldn’t leave my bed, I was too lazy to even wash in the morning, brush my hair, but I never went to court without brushing my hair, doing my nails, perfume, make-up, or even wearing the same outfit twice.’

‘I live alone. My daughter is based in Tbilisi. I am the kind of person that if I fall into a pit and I don’t have a ladder, I will not become hysterical and start yelling. I don’t suffer over things I cannot change.’

‘This situation required calmness from me, being able to follow the court case until the end, being strong. This is exactly what my lawyer recently told me.’

‘He is a cold person, but he hugged me and told me he really admires me because I had stayed strong for all this time. He said he didn’t expect me to stay strong for so long.’

‘In the beginning, when we were agreeing to cooperate, he told me that he would only take my case if I wouldn’t take a deal. I told him that my future here depended on the case and I didn’t plan to take any deals.’

‘I received some offers, that if I met [the authorities] I would get some assistance, but I knew that they would request silence in return. I told them I would meet them only after the case was over.’

‘My daughter got married while I was under house arrest. I tell myself I need to live and stay healthy, but not because I may have grandchildren and want to meet them, I am ashamed to say this, but I need to stay strong and alive to win this case. My main goal is to win this trial. My whole life now revolves around that.’

‘What kind of partner can such a person be?’

‘When I was acquitted [in the second instance court] people kept telling me that I had to get married, settle down and stop engaging in politics. It made me angry, I even spoke to a few of them very harshly.’

‘A day will not pass without someone telling me that. I tell them that I fight my fight not because I am single, but because I have more civic consciousness, responsibility, and bravery to demand answers from the government, to demand the opening of borders, transport, water, etc.’

‘If you are active, does this mean you lack relationships with men. I meet men who in person will tell me they support me but cannot even dare to like my Facebook posts. What kind of husband or partner can such a person be?’

‘I was married in the 1990s and had a child. My husband was Ossetian; he bridenapped me and no one reacted negatively to it. Having relationships with each other [Georgians and Ossetians] was normal. My grandmother is Ossetian, we have many Ossetian relatives and we were always on good terms.’

‘Four other girls were bridenapped that day too. I know for sure that at least three of them have divorced.’

‘Our family didn’t work out.’

‘How else will they achieve reconciliation or anything else?’

‘The approach of the Georgian government from the very beginning has been to offer that I leave. They cannot solve the problem, but why should I leave? If I need to leave, I will know this myself.’

‘They could at least try to give me some consolation with words. No one even met our family. No one offered to meet them. The government could at least have met my lawyer and cooperated with him. He is a very qualified, trusted person, independent and objective. But they are not interested.’

‘The government finds it difficult to even say my surname, they try to block my case on Georgian television as well. I find it difficult to understand how it’s not interesting for Georgian television to at least make a half minute report about a civic activist winning a case in court in South Ossetia. Do I need to die in order to become interesting for them?’

‘Netgazeti once asked [former Georgian Prime Minister] Bakhtadze live about me. He should have known about me but he didn’t. I’m sure [Prime Minister] Gakharia hasn’t heard of me either.’

‘It’s very easy to tell how informed the government is. They speak with the template that Russia is guilty. Whatever’s happening in my case — how Russia is related to it.’

‘The Georgian government is the last to announce what is happening here and very often it is based on information from RES [a South Ossetian state-owned news agency] or Sputnik. I am sure they don’t even read other media outlets like Ekho Kavkaza, or Georgian outlets.’

‘Some online media outlets work really well. I like that they try to use neutral terminology; this creates trust. It’s better if we have some kind of cooperation. How else will they achieve reconciliation or anything else?’

‘What is their vision? That these barbed wires will be demolished like the Berlin wall?’

‘Maybe it’s satisfying to hear in Tbilisi and for foreigners that [the government] is creating some projects, that they have this ‘step for better future’, which they have kept repeating for two years, but they just talk about it.’

‘What we see in reality is that Georgian schools shut down. Tens of people left because of that. There is outmigration. People leave their houses, the border remains closed, there are restrictions, prohibitions, and people leave.’

‘And in the end, when this project really starts to be implemented, who will they rely on here?’

‘If I’m ever able to go out to meetings and conferences, I will definitely ask about this. It seems to be a lie that they have contacts here. The minister [of reconciliation and civic equality] has met just one Ossetian woman here for the past three years and it happened with the help of a lot of mediators. No one trusts the minister. I live here and I want to live here and this woman disrupts our life.’

‘What is their vision? That these barbed wires will be demolished like the Berlin wall? but how? They have no one to contact here, they don’t have people here who trust them.’

‘What on earth does Russia have to do with it?’

‘They [the government] keep talking about “Russia”. They kept talking about “Russia” with my case as well. What on earth does Russia have to do with it?

‘If you remember, the road was blocked for two and a half months last January as well. What did the Georgian government do? Exactly that: “Russia, Russia, Russia”.’

‘I don’t know, maybe I’m wrong, but I think the Georgian Government should have appealed to the European Court of Human Rights for the restriction of freedom of movement. This was huge and now [with the closure of the border], we are locked up again, but maybe we could have avoided it.’

‘I know people here who had to miss planned chemotherapy, some cancer patients who couldn’t have planned surgery. Why not dispute this? That people have no access to healthcare, movement, and so many other things.’

‘They are in power, they are lawyers. If you cannot do anything — then leave — and maybe others will succeed.’

‘I cannot imagine living somewhere else’

‘If the court finds me guilty, I will not run away, I will go to prison. As far as I know, there are only two women in prison here out of 56 or 58 prisoners. After all, they will not beat me there. Their [South Ossetians’] leader, Alla Dzhioyeva used to be in prison here so why couldn’t I be? I will not accept any deals.’

‘Sometimes I joke that I will at least learn Ossetians and teach Georgian there. Then I will be requesting to organise plays in prison.’

‘I had no idea how the Prosecutor’s Office or militia worked here until I was arrested. If I go to prison, I will see how that works too and it will be another experience.’

‘If the court acquits me, the first thing I want to do is sue the Prosecutor’s Office, to claim my belongings back. I don’t plan to immediately cross the border. I want to fight for rehabilitation and demand that those who took more than two years of my life be punished and to demand compensation.’

‘The next step is to fix my teeth. Sometimes I think that I’m becoming old, I need to pay more attention to myself. I want to do medical checkups and make sure I’m healthy and then I want to take a holiday. It doesn’t matter where, but somewhere where I will not think of all of this.’

‘I want to go somewhere and rest, dance, sing, have fun, but now the road is closed, even if I’m acquitted again, I won’t be able to go anywhere. I want to work out more.’

‘I have a little dream for Tbilisi too — I want to take dancing classes, I really want to. I also want to take make-up classes. We don’t have any salons here [Akhalgori]. I would love to do peoples’ make-up here, so I want to learn it.’

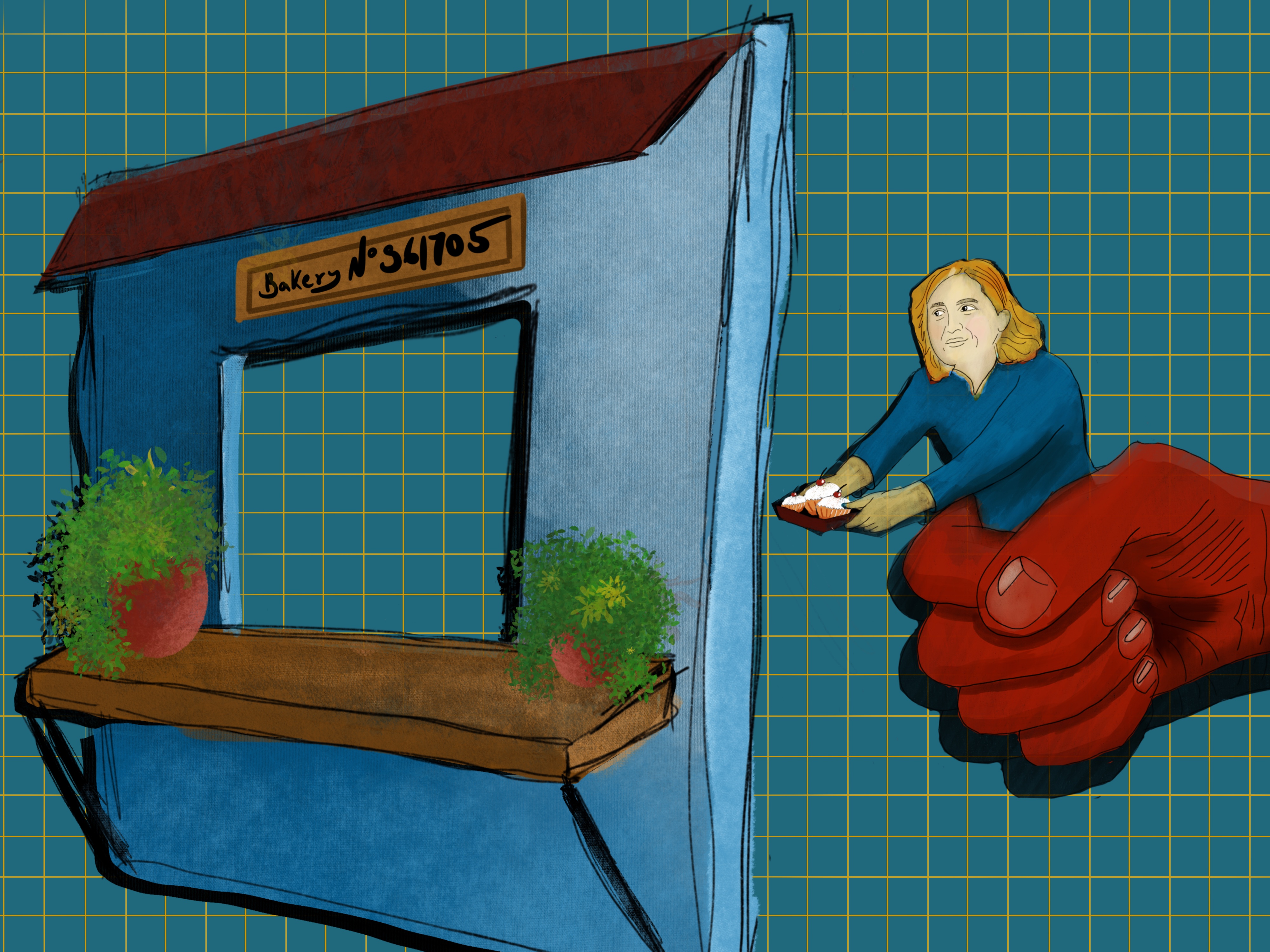

‘One day, if I stay longer in Tbilisi, I want to open an Ossetian bakery. I want to name it “bakery number 961705” after my case number. It’s funny, but I want to do it.’

‘These are my plans, mainly, I don’t plan to give up and I don’t plan to move out from here and live somewhere else. If I’m compensated by the Prosecutor’s Office I may buy a flat in Tskhinvali too.’

‘For all these 44 years I never had a desire to leave Akhalgori. When I went to Tbilisi I would never stay an extra day; I would take the last bus home. I want to be here, I cannot imagine living somewhere else.’

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.