A row between the Armenian Government and former officials from Nagorno-Karabakh is continuing over attempts to form a government-in-exile out of Yerevan.

On Monday, the leader of Ardarutyun, a political party from Nagorno-Karabakh, told RFE/RL that anyone who opposed the continued functioning of Nagorno-Karabakh’s state institutions supported the ‘destruction of Artsakh’s [Nagorno-Karabakh’s] statehood.’

Similarly, in a thinly veiled attack on the Armenian Government last week, a group of former MPs from Nagorno-Karabakh decried the ‘intensity of steps’ being taken and the ‘aggressive behaviour’ of ‘parties interested in the final closure of the Artsakh issue.’

The MPs made the statement following a visit to the Yerablur Military Cemetery in Yerevan on the anniversary of the disputed 1991 independence referendum in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Armenian officials have grown increasingly hostile to the idea of proposals to form a government-in-exile, warning it could be used by Azerbaijan as a pretext to take military action against Armenia.

On Sunday, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan spoke about the ‘inevitability’ of Nagorno-Karabakh’s dissolution due to the negotiation status his government inherited after coming to power in 2018. And on Monday, in response to the statement by former MPs from Nagorno-Karabakh, the deputy chair of the ruling Civil Contract Party, Gevorg Papoyan, accused them of posing a direct threat to Armenia’s security.

‘They signed a capitulation agreement, disbanded the Nagorno-Karabakh army, handed over weapons to Azerbaijan, dissolved the Nagorno-Karabakh National Assembly and came to Armenia — now they want to hold a parliamentary session here?’

‘Is this a ticking time bomb in Armenia?’, asked Papoyan.

After Azerbaijan attacked Nagorno-Karabakh in September, forcing the government’s surrender, President Samvel Shahramanyan issued a decree to dissolve the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and all of its state institutions.

Earlier in November, Papoyan had stressed that Armenia could not allocate funds to Nagorno-Karabakh’s state institutions.

‘We should not do such things that would give the other side an opportunity to challenge the territorial integrity of Armenia and torpedo the peace process’, he stated.

A continued push for a government in exile

Other officials in Armenia have voiced similar sentiments.

In mid-November, the speaker of the Armenian Parliament, Alen Simonyan, said that establishing a government in exile would be a ‘direct threat and a blow to Armenia’s security’.

And in late November, Armenian President Vahagn Khachaturyan said that the establishment of a Nagorno-Karabakh government in exile was unnecessary.

‘There is a Republic of Armenia, whose institutions are functioning. What function should they [Nagorno-Karabakh] perform? Armenia protects the rights of Artsakh Armenians’, Khachaturyan told reporters.

However, since fleeing the Azerbaijani takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh in September, many officials have insisted that they continue to represent the region’s former ethnic-Armenian population.

In late October, Nagorno-Karabakh’s last president, Samvel Shahramanyan, disowned the surrender document dissolving Nagorno-Karabakh, stating that a ‘republic created by the people cannot be dissolved by any document’.

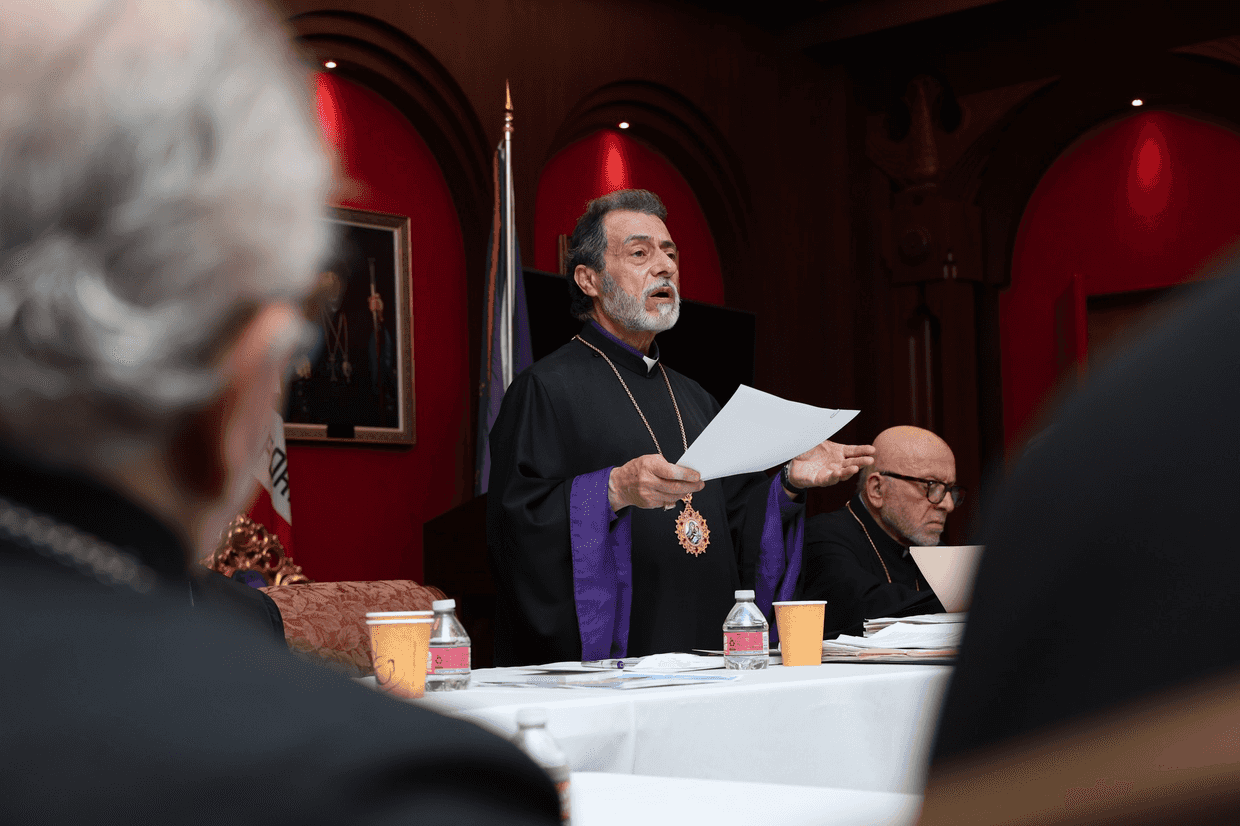

A few days later, Shahramanyan and a group of former Nagorno-Karabakh officials gathered in Yerevan to discuss ‘preserving the statehood’ of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The meeting was organised by the Committee for the Preservation of Artsakh Statehood, founded by Suren Petrosyan, an Armenian opposition figure.

Petrosyan dismissed concerns that a government in exile based in Armenia could put the country at risk of an Azerbaijani attack because the Armenian government would not be involved in a Nagorno-Karabakh administration.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.