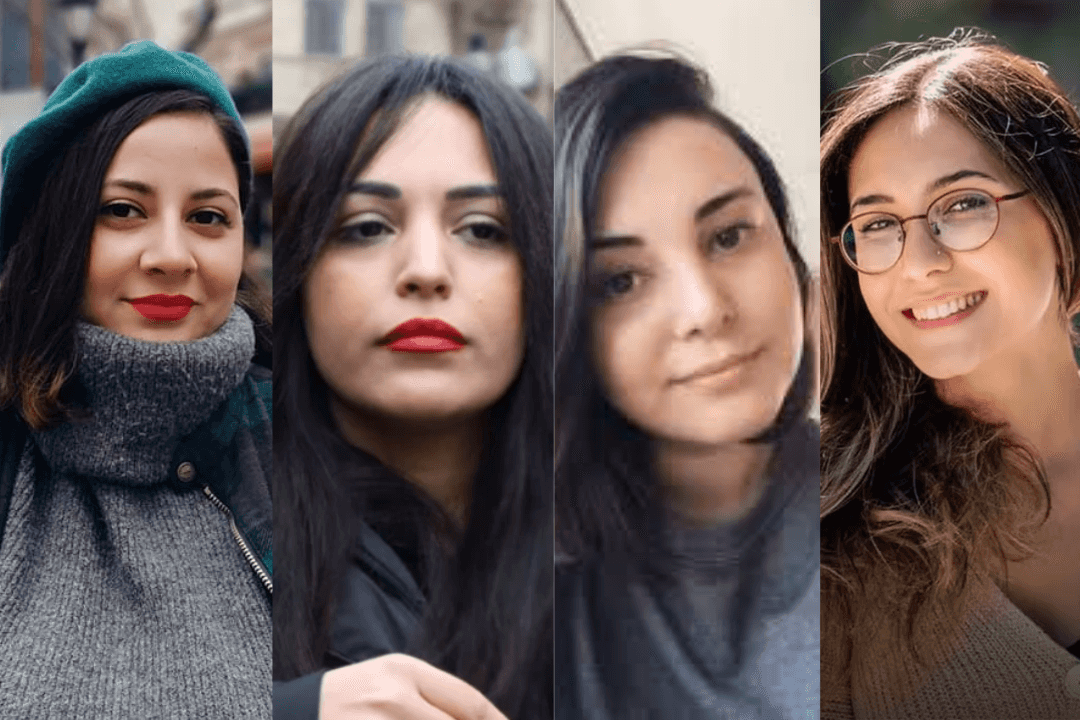

Sevinj Abbasova, the imprisoned editor-in-chief of independent Azerbaijani media outlet Abzas Media, and Elnara Gasimova, a journalist sentenced in the same criminal case, have both written letters describing the difficult conditions they faced in prison during a five-day hunger strike in support of Abzas Media director Ulvi Hasanli.

Hasanli began his own hunger strike on 20 July, demanding that the authorities transfer him from the more secure Umbaki Prison in Baku’s suburbs to a more central pre-trial detention centre.

Two days later, Abbasova, Gasimova, and journalist Nargiz Absalamova began their own hunger strike in prison in support of Hasanli. On 28 July, the three journalists ended their hunger strike after taking into account the health problems of their respective family members. Hasanli ended his hunger strike the following week on 5 August.

On Monday, Abzas Media published a letter penned by Abbasova from prison, describing the situation in the detention centre after the three journalists had decided to end their hunger strike.

Abbasova began the letter by stating that the date chosen to begin the hunger strike was ‘very symbolic’, coinciding with Azerbaijan’s National Press Day — the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the press in the country.

She then noted that they were informed prison authorities would meet with them. After no one came, however, Abbasova returned to her cell.

‘When I returned, I went to a room for two [people], but they left me alone. I greeted the ants crawling on the wall. My roommates ask the guards to clean the room, but it doesn’t help. I didn’t want to [insist], so I cleaned the room alone and put things away. Our things are checked beforehand so that we cannot hide food and eat secretly’, Abbasova stated.

There was no shower in her cell, and Abbasova said that women were ‘forced to wash themselves on their knees’.

‘The tap for washing hands and faces also barely works, and the water flows slowly. Although it is the middle of summer, the windows have not been removed. The prisoners in this room have only one window for ventilation’.

Additionally, Abbasova wrote that the TV in the room did not work, and that the exercise yard was not available for three hours.

‘The next day, everything repeated itself. The exercise area in all the cells were [ supposed to open at 9:00], but the door to my room and that of the girls’ was not opened. After two hours of breathlessly shouting, “Elnur Ismailov, open our walking areas”, at 12:00 they opened the door for us. They again gave the same reason — they needed to report to the chief. The next day, the chief did not need a report, and the doors were opened on time’, Abbasova wrote.

The rest of the shower, including the head and the cord, were only brought five days later.

Since they began their hunger strike, cold water was reduced from two hours to 40 minutes a day, while hot water was completely cut off.

‘About 350 prisoners living on three floors suffered from thirst for three days. Female prisoners began to complain that it was because of us [...] why should they suffer because of journalists?’ Abbasova wrote.

No air, no phones, no water

The journalists faced numerous restrictions during their hunger strike.

When Gasimova called to tell her family to inform them about her hunger strike decision, her phone was disconnected, and the phone was not available for several hours.

‘When the female prisoners asked, “Why isn’t the phone working?” guard Jahan Ibrahimli replied, “It’s because of the politicians. Believe me, we’re tired of them.” The Senior Warden Aziza Mammadova also added, “A prisoner closes the door on another prisoner”. The women in the reception area then started yelling at Elnara. “It doesn’t matter that you don’t have children, but we need to talk to our children”, one prisoner complained’, Abbasova said, describing how the head of the prison tried to provoke a fight with the other prisoners.

Gasimova described similar problems in a letter Abzas Media published on Tuesday.

She stated that she was also placed in a cell that was only for two people, and ‘since there is no ventilation in the room, the window glass was removed to have at least some air in the summer. But in this room, almost all the windows were in place’.

The journalist noted that there was no light in the room, the wire to which the lamp was connected was torn off, and the lamp itself was also missing.

‘When I asked to call a repairman for repairs, after many persistent requests, he was “located”. The device necessary for the TV to work was missing, and the removed one was not replaced with a new one. This was fixed later that day’.

‘On the morning of 28 July, deputy chief Javid Gulaliyev came to the cell with an employee and a doctor. The employee next to him began to search the room. Probably, Gulaliyev resorted to this method, suspecting that we were starving’, Gasimova wrote.

The doctor measured her blood pressure, and upon hearing that it was normal, Gulaliyev stated, ‘Someone possibly giving them breakfast’.

‘Seeing that our blood pressure was normal at that moment, the deputy chief was probably very disappointed. After measuring the pressure, the doctor took my blood for analysis. The deputy walked along the corridor and said, “I will find this traitor, we will see who is feeding them” ’, Gasimova wrote.

That same day, the doctor again entered Gasimova’s cell and told her that her blood sugar level had dropped significantly. He offered to provide her intravenous therapy, but she refused.

‘Around 19:00, we submitted applications to end the hunger strike. A little later, we were taken one by one to the reception room of deputy chief Jeyhun Hajiyev, and we wrote an explanatory note about ending the hunger strike. After that, we were returned to our rooms’, Gasimova concluded.