In an increasingly polarised media environment, Georgians have mixed feelings about how much TV and TV journalists can be trusted.

Over the past decade, TV as a source of news has been on the decline in Georgia. With just 53% of those surveyed in 2021 using TV as their primary news source, as compared to 88% in 2009, it is clear that TV has lost its dominance. Nonetheless, it remains the main news source for half of the adult population.

This fall in TV consumption has taken place against a background of an increasingly divided media environment. Media monitoring studies show that, in recent years, there have been clear trends of polarisation amongst television channels, with many strongly supporting either the ruling party or the opposition.

This has been reflected in qualitative studies by CRRC-Georgia, in which many people have said that they have to watch news on several television channels to be able to draw reasonable conclusions on events that have happened and how they might interpret them.

In such an environment, what does the Georgian public think of television and TV journalists?

Can TV be trusted?

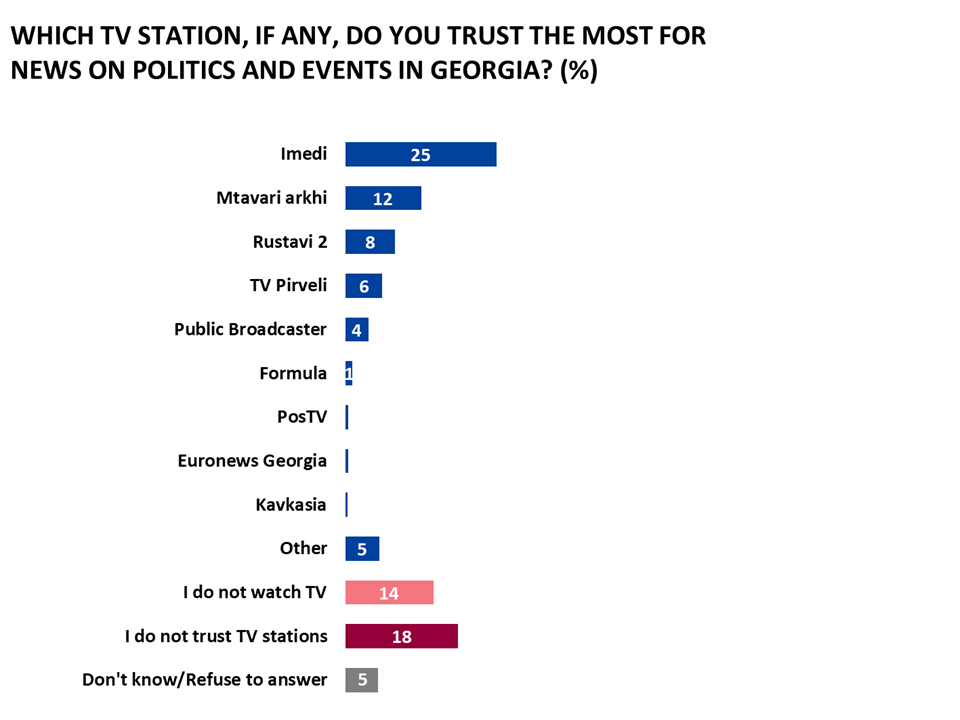

According to the Caucasus Barometer 2021, an annual household survey run by CRRC, 18% of the population does not trust any television channel for news about politics and current events and 14% does not watch television news at all.

The most trusted television channels for news on politics and current events were found at opposite ends of the political sprectrum – the pro-government Imedi, trusted by a quarter (25%) of the population, and the pro-opposition Mtavari, trusted by 12%. Less than a tenth of the population trusted Rustavi 2 (8%), TV Pirveli (6%), and the Public Broadcaster (4%) more than any other station.

A regression analysis found that trust in TV and TV stations and viewing habits were associated with various demographic characteristics.

Older people were more likely to watch and trust TV compared to other age groups.

Ethnic minorities were more likely to distrust TV or not watch it compared to ethnic Georgians. This could be in part related to a lack of Armenian- and Azerbaijani-language programming on Georgian television.

Working people were more likely to distrust and/or not watch TV news compared to people who did not work.

People who supported a political party were more likely to watch and trust TV than people who did not support any party, or refused to report a party preference.

There were no patterns associated with settlement type, gender, or education level.

Note: The analysis uses a multinomial regression, where the dependent variable is whether people distrust TV, do not watch any TV channel for news about politics and current events, or trust a specific TV station. The independent variables are gender, age group, ethnicity, settlement type, level of education, and employment status.

What do the public think of TV journalists?

With a third of the population distrusting and/or not watching news on any television channel, what does the Georgian public think of the performance of TV journalists?

About half of those surveyed (48%) believed that Georgian TV journalists inform the population about ongoing events in Georgia neither poorly nor well, while approximately a fifth of the population either positively or negatively assesses their work.

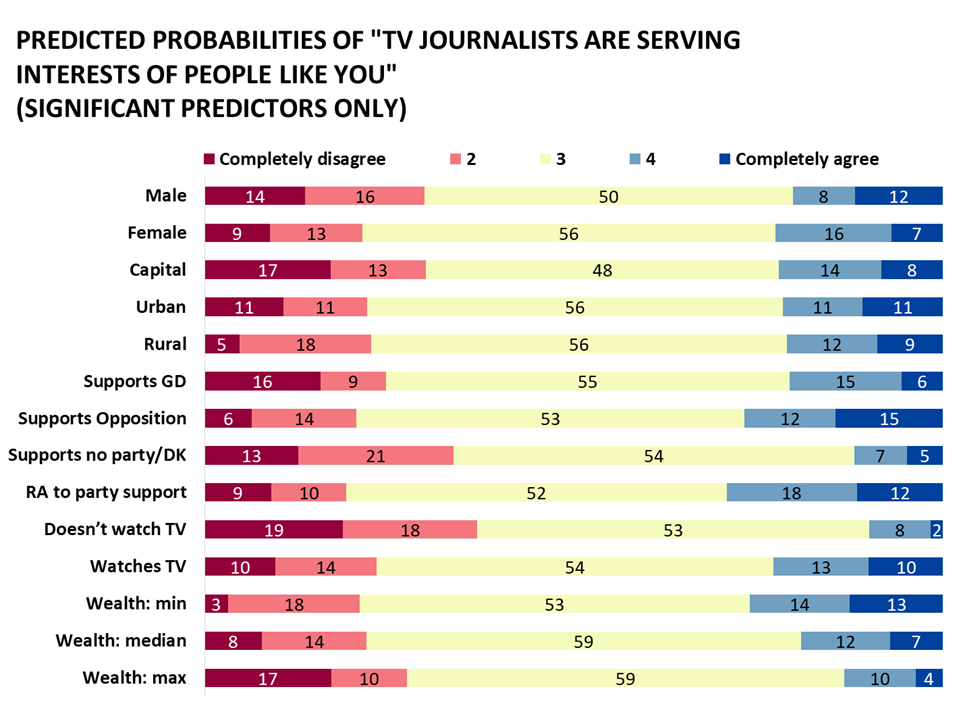

A multinomial regression showed that women were more likely to agree with the idea that TV journalists were serving their interests than men were. On the other hand, people living in urban areas assessed the performance of TV journalists more negatively than those living in rural settlements.

Party allegiance was also a significant predictor of people’s views: respondents who supported an opposition party were more positive towards the performance of journalists than supporters of the ruling party, Georgian Dream.

Wealth (measured as the number of items a household owns from a list of 14) was also a significant predictor: poor people assessed the performance of journalists more positively than wealthier people.

Unsurprisingly, people who watched TV tended to feel more positively about TV journalists than people who do not watch TV.

A regression analysis did not show significant differences in attitudes between different age groups, ethnicities, people with different education levels, or with and without a job.

Note: The analysis uses a multinomial regression, where the dependent variable is whether people agree or disagree with the statement that TV journalists in Georgia are serving the interests of people like them. The independent variables are gender, age group, ethnicity, settlement type, level of education, wealth, watching TV and employment status.

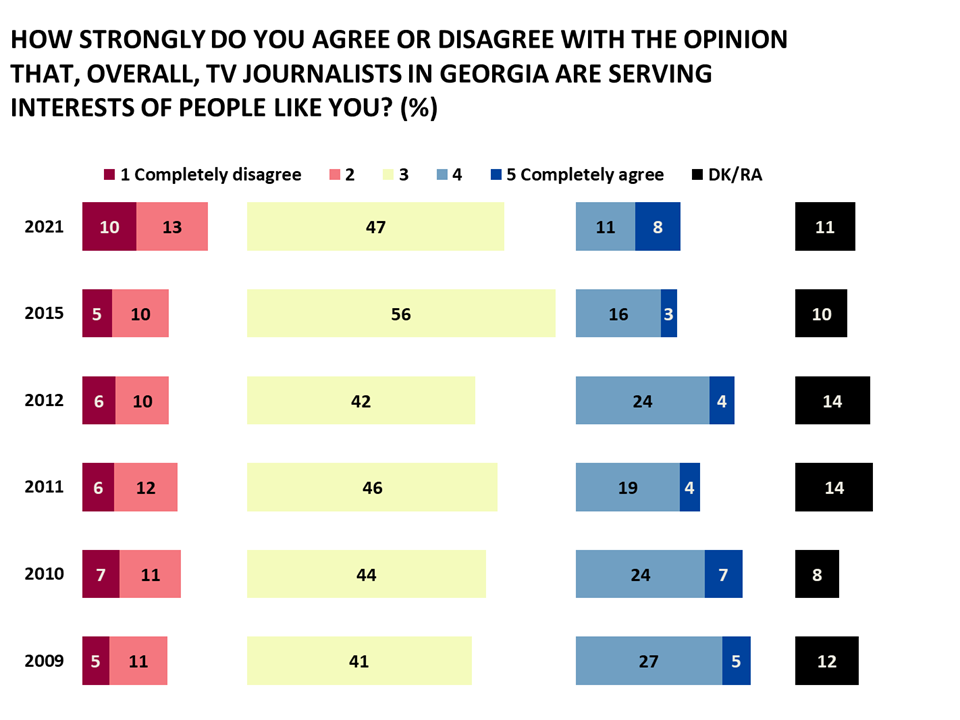

The data shows a similar pattern with regard to views on whether TV journalists in Georgia serve the interests of the people. Slightly less than half of the population in Georgia (47%) neither agree nor disagree, while around a quarter (23%) believed that TV journalists do not serve the interests of the people, and a fifth (19%) believed that they did. Notably, people have become more pessimistic with regards to this question over the last decade, with a seven percentage point increase in disagreement with this sentiment between 2009 and 2021, and a 13 point decline in agreement with the statement during the same period.

In the context of a very divided media landscape, it is notable that there is low public trust in television news and outlets. This trust appears to have fallen over the past decade, with fewer now believing that TV journalists in Georgia serve their interests.

The data used in this post is available here.

This article was written by Kristina Vacharadze, Programs Director at CRRC-Georgia, and Mariam Kobaladze, Senior Researcher at CRRC-Georgia. The views presented in the article are of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.