The latest report by the Institute for Democratic Initiatives, independent Azerbaijani NGO, shows a spike in the number of administrative arrests, which are used as a ‘tool of political pressure’ in the country.

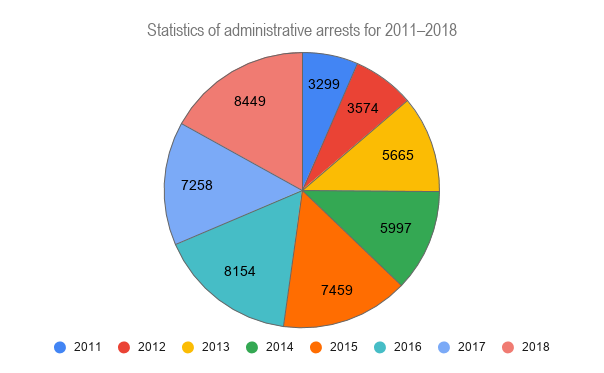

According to the report, in 2011–2018 the number of administrative arrests in Azerbaijan increased more than twofold — while in 2011, 3,299 were arrested, in 2018, this number increased to 8,449.

The document states that despite the fact that according to the law administrative arrests should be used in exceptional cases, in Azerbaijan they have become a mass occurrence.

The report also says that according to 2011–2018 statistics, warning as a measure of administrative punishment has gradually become used less —from 4,368 warnings in 2011 to only four in 2018.

According to the authors of the report, in 2018, 78 arrests were clearly politically motivated, although the real number is likely much higher, as it doesn’t account for mass arrests during rallies.

The report says that civil society activists are being subjected to administrative arrest for their social and political activities, and not because they have committed any administrative violations. These arrests, the document says, are politically motivated and implemented without a fair trial, or adequate protection, and made by the decision of local courts based on police statements.

The report also analyses the conditions in detention centres, as well as maltreatment, based on interviews with 15 detainees on political charges.

Tightening the regulations

The analysis indicates that despite the fact that administrative arrests were used as a method of political pressure also in previous years, they became more frequent after the adoption of the amendments to the Code of Administrative Violations in 2013. This was prompted by peaceful actions and flash mobs held in Baku city centre in 2013. In particular, legislative amendments to toughen sentences were introduced after the anti-hazing ‘End Soldiers’ Deaths’ protest.

From 2014, according to the amendments, the document says, a person can be held under arrest up to three months, while previously it was 15 days. The detention period was raised from 24 to 48 hours.

Since 2016, administrative arrests have begun to be carried out even during rallies agreed with the government, the report says.

‘Starting from 2016, new practice started being applied, when a few days before the scheduled day of the rally, public activists, especially members of the opposition parties, were summoned to the police station, warned, threatened, fined, and the ones who played an important role in organising the rally and the organisers of the rally were subjected to administrative charges for disobeying police’, the report says.

According to the document, for the past two years, 90% of the arrests of public activists are made due to ‘disobedience to police’.

Administrative arrests on political grounds in 2018

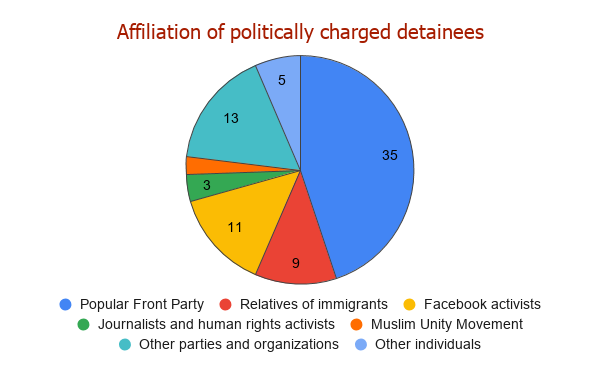

The report says that from 8,449 administrative arrests in 2018, 78 arrests were made on political grounds, wherein most of those arrested were members of the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan.

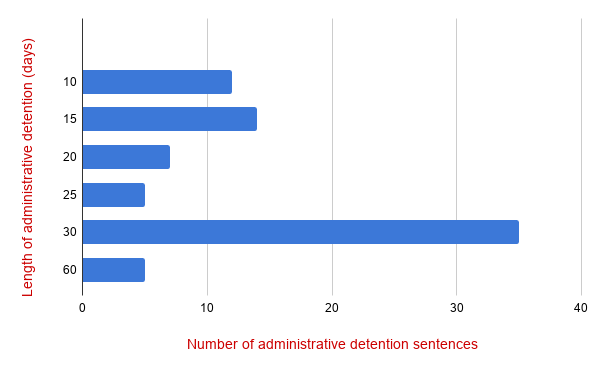

‘In three coordinated rallies held by the National Council [a coalition of opposition forces] during the 11 April 2018 presidential elections, 174 people were summoned to police departments, 17 of them were sentenced to from 10 to 30 days in administrative penalties for resisting police, and the rest were punished in the same way or released with a warning’, said in the document.

In 2018, in connection with the 100th anniversary of Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, the ReAl party and many civil society activists visited the Declaration of Independence monument. After the visit, the report says, the participants were not allowed to march to Baku Boulevard. According to the document, the day after the event, more than 10 people, including the ReAl Party vice chairman, were summoned to the police station. Four of them were sentenced to 25 to 30 days of administrative arrest.

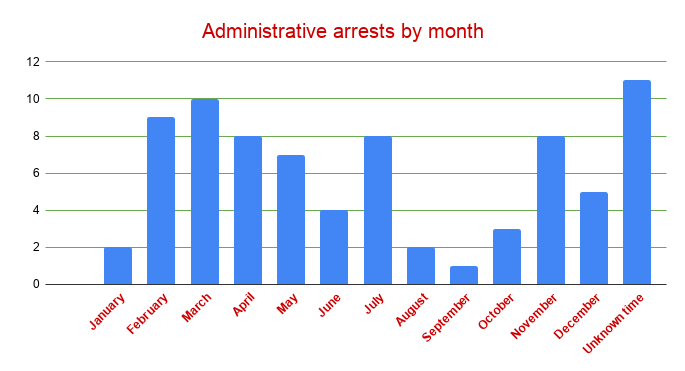

During this period, according to the report, most arrests were made in March, and the least arrests were in September. 55 detainees were subjected to administrative arrest due to the disobedience to police.

Maltreatment and conditions in detention centres

Maltreatment and conditions in detention centres

The authors of the report interviewed 15 people arrested for administrative violations on political grounds about maltreatment and conditions in detention centres. The interviewees for the report were from People Front Party, ReAl and Musavat parties, D18 movement, and other individuals.

According to the interviews, in many cases, detainees were subjected to inhuman treatment both in police stations before the court verdict was announced, and in temporary detention centres after the court decision was announced, by being held in substandard conditions or being physically and psychologically abused by police.

The document notes that the detainees were not provided with a lawyer, as state-provided lawyers carried out direct orders from investigative bodies. Detainees were not provided with daily newspapers, medical examinations were not routinely conducted, telephone calls and meetings were not allowed. In some cases, the report says, detainees were even tortured.

During the interviews, the respondents noted that the main problems they faced during administrative arrest were poor quality of food, no access to bathing facilities, sleeping restrictions, and other problems.

In addition, the report notes, those subjected to administrative arrest say that they were taken to police stations without any justification and the courts convicted them to administrative arrest without a fair trial, based on police reports. Courts generally consider the opinions of law enforcement agencies valid.

According to the report, despite numerous complaints and allegations of torture and maltreatment of suspects, including those sentenced to administrative arrest, these allegations are not objectively investigated by either the higher law enforcement agencies or the courts.