Explainer | What to expect from Georgia’s ‘scheduled revolution’ on 4 October

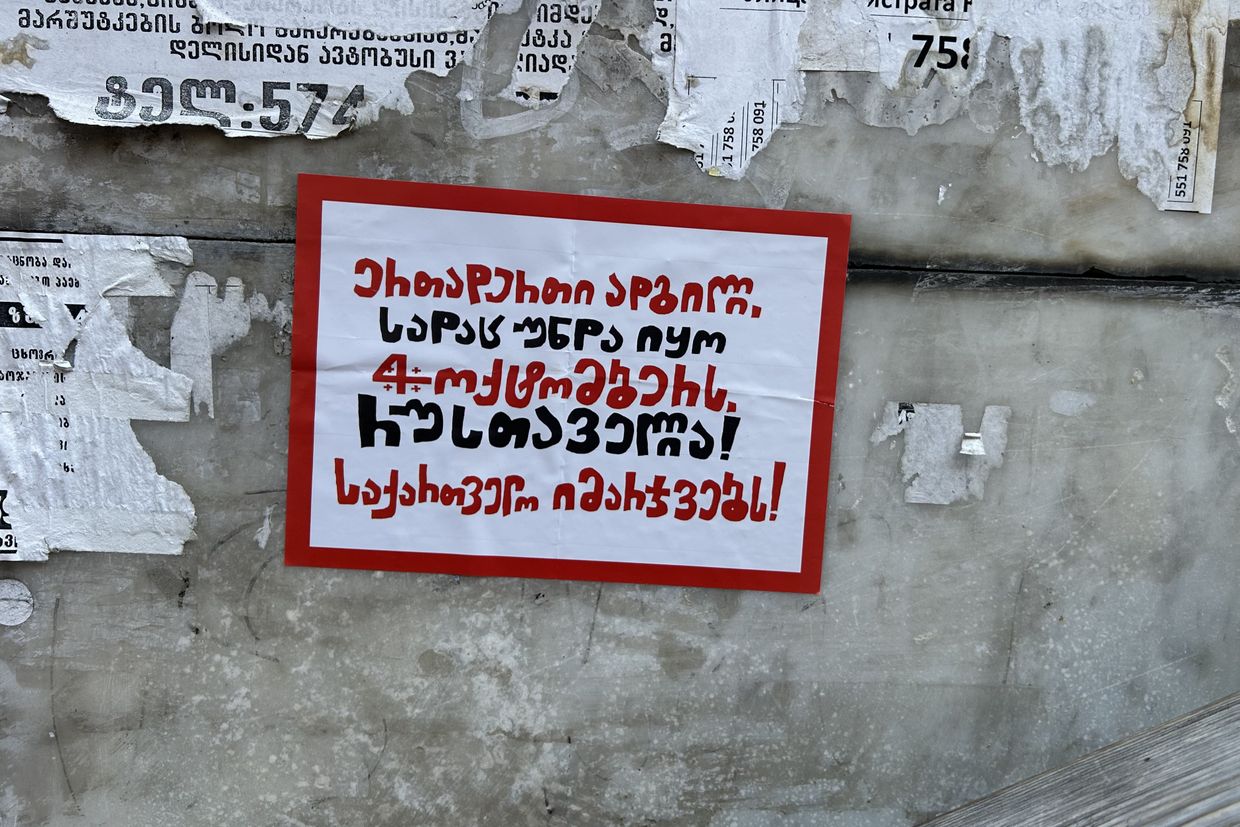

While some Georgians will vote in partially boycotted municipal elections on 4 October, calls for a ‘peaceful revolution’ are also being made.

On 4 October, less than a year after Georgia’s disputed 2024 parliamentary vote, elections will take place in all 64 municipalities across the country to elect municipal councils and city mayors.

Against a backdrop of rising authoritarianism and doubts about the integrity of the vote, two of the four major opposition groupings (as well as a number of smaller parties) have announced they intend to boycott the vote. They argue that participation would only legitimise the Georgian Dream government and undermine the strategy of non-recognition and isolation.

Lelo–Strong Georgia and For Georgia — two other opposition groups — have chosen to participate, arguing that taking part could help sustain anti-government momentum and prevent Georgian Dream from consolidating control over all state institutions.

Their differing choice further divided Georgia’s already fragmented opposition, sparking verbal clashes, mutual accusations, and casting even more doubt on any prospects for future unity.

As debates over the boycott have continued, anticipation for 4 October has also risen for another reason, to the oft announced anti-government rally in central Tbilisi planned for the same day which some are already hailing as a day of revolution.

A ‘peaceful revolution’

From the outside, there may seem to be nothing new in the announced protest: since the government’s EU U-turn on 28 November, central Rustaveli Avenue — home to parliament — has been closed for several hours every night.

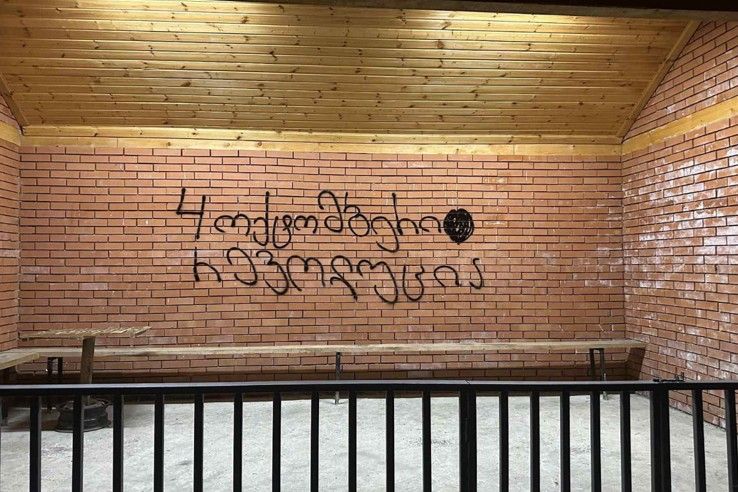

However, 4 October stands somewhat apart from these ongoing protests: its promoters are trying to convince people that it is possible to topple the Georgian Dream government on that very day.

The idea of holding a protest in Tbilisi on election day was first announced in early June by opera singer and opposition figure Paata Burchuladze. He called the event a ‘National Assembly’, where Georgians were to gather and ‘take power into their own hands’.

Burchuladze made the goal of the rally clearer on 31 July when he and others read out a statement in front of the Government Administration in Tbilisi and declared 4 October as the day of ‘Ivanishvili’s peaceful overthrow’ — a reference to Bidzina Ivanishvili, the billionaire founder and honorary chair of the ruling party.

‘The 4th of October will not just be a date of protest, it will be a day of historic victory,’ Burchuladze declared in a video address that remains pinned at the top of his official Facebook page.

Burchuladze’s calls soon gained support. Levan Khabeishvili, the now-jailed chair of the political council of the opposition United National Movement (UNM), also spoke of the need to ‘overthrow Ivanishvili’s regime’.

‘The 4th of October is a natural deadline, when hundreds of thousands of Georgians must take to the streets and return power to the people,’ he said on 23 June while commenting on the arrests of opposition politicians.

Over the summer, the announced demonstration became more clearly branded with the term ‘peaceful revolution’.

‘If a politician refuses to take part in the “elections” of an illegitimate government, then the alternative is peaceful overthrow, a peaceful revolution!!! There is no third option!’ Khabeishvili wrote on social media on 20 August.

Emulating Pashinyan — is there a plan?

Announcements of the 4 October demonstration grew more frequent over time, as other figures from the UNM and its smaller partner party, Strategy Aghmashenebeli, as well as several anti-government activists joined in.

The promoters have stated that the protest will be both swift and decisive — with Burchuladze declaring: ‘We begin on the fourth and finish on the fourth’. Another opposition politician, Murtaz Zodelava, said he already imagined a ‘new Georgia’ from 5 October.

The calls came as the protests in Tbilisi, now in their 44th week, have continued to dwindle in size, amid growing fatigue. This has led some to suggest that a pre-announced date for a revolution could inspire people to return to the streets.

However, in response to the promised ‘overthrow’, journalists and others have repeatedly asked the same question: how?

Georgia’s recent history is replete with opposition-set deadlines and ultimatums to governments, yet since the Rose Revolution of 2003, the country has not seen a government forced out by street protests.

‘What should we do? We must act. Act completely peacefully’, Khabeishvili said on 10 September during an interview with the opposition-leaning TV Pirveli.

Explaining what he meant by a ‘peaceful overthrow’, Khabeishvili referred to the 2018 Velvet Revolution in Armenia, which led to the resignation of then-Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan and saw Nikol Pashinyan, one of the movement’s key figures, become the country’s leader.

‘[Sargsyan’s] regime fell peacefully, and it was Pashinyan who did it. We are following the Strategy of Pashinyan. How will we do it? […] Two people chase and intimidate a hundred people. We have only one thing to do: those hundred people must see one another and simply confront [those two] together’, he said.

Khabeishvili has not positioned himself as the protest’s Pashinyan, however. According to him, he simply joined Burchuladze’s initiative and took on his share of responsibility — something every citizen who wants to participate should do.

‘When people ask if it’s possible to finish it on the fourth: yes, it is! But it depends on whether a Georgian citizen shows up’, he added.

So far, only one concrete detail about the 4 October rally is known: the gathering starts at 16:00 Tbilisi time.

Khabeishvili said he would reveal details ‘gradually’, but if there is in fact a concrete plan, he won’t be the one to share it himself: Khabeishvili was detained on 11 September.

The government responds

Georgian Dream has responded to the calls for a revolution on 4 October by dismissing Khabeishvili, perhaps its loudest proponent, as unserious.

And yet, authorities have moved to silence him. Four days after his arrest, the State Security Service (SSG) barred him from making phone calls or sending letters from prison.

Khabeishvili’s arrest stemmed from an interview he gave the day before he was arrested, in which he offered riot police $200,000 not to disperse protesters — a statement the SSG classified as a bribe.

He was later charged with a second offence, calling for the overthrow of the government. Altogether, he faces up to seven years in prison.

The ruling party has also repeatedly warned that any unlawful acts will be met with a response.

‘If anyone dares break the law, everyone will see the strength of the new management of law enforcement’, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze said on 22 September, referring to recent personnel reshuffles in law enforcement agencies.

For Khabeishvili, his arrest signifies that Georgian Dream has ‘seen [its] defeat’.

He argues that the ruling party has already ‘collapsed’ from inside and is being consumed by internal conflicts — something he frequently spoke about on opposition-leaning TV channels before his detention. This was followed by accusations from officials, including Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze, that Khabeishvili was being financed by unnamed defectors from the ruling party.

A (dis)united front?

Opposition parties and other government critics have expressed differing views on 4 October’s ‘planned revolution’.

Irakli Kupradze, Lelo’s general secretary and the joint opposition candidate for Mayor of Tbilisi, urged citizens to vote in the morning and attend the protest in the evening, while distancing himself from responsibility for what might take place there.

‘Once voting ends and we finish securing the votes, we will be on Rustaveli Avenue […] but, of course, we cannot take responsibility for what we aren’t organising or don’t know the scenario for’, he said.

For Georgia has been more critical of the ‘peaceful revolution’ plans: its leader, ex-prime minister Giorgi Gakharia, called it an ‘uncertain project’ with ‘violent overtones’ which the ruling party could exploit to its advantage.

‘Then they will point fingers at the people, saying not enough showed up — what can we do?’ he said from abroad, where he has been since June amid ongoing investigations into his time as prime minister.

However, divisions around the rally do not neatly align with the lines between election boycott supporters and opponents.

Some boycotters suggest that tying expectations for change to a single date could set the stage for disappointment.

Elene Khoshtaria, who until her arrest on 15 September was the only Coalition For Change leader still outside prison, said in July that ‘world history has never seen a precedent of a pre-announced revolution’. Anyone who sets such a date in advance, she said, was either ‘a clownish liar or a useful idiot’.

Khoshtaria later met with Khabeshvili and apologised on social media, pointing to the futility of public disputes within the opposition, though she stressed that her stance on the 4 October rally remained unchanged.

Tamar Chergoleishvili, founder of the boycotting Federalists party, is also sceptical of the plan. While noting that protesting itself was a good idea, she argued that ‘making a mockery of citizens’ expectations is harmful’.

‘It is wrong to set any date and hand Bidzina Ivanishvili’s propaganda machine the chance to brand something as our defeat, especially when the regime itself is failing’, she told the Georgian Public Broadcaster (GPB) earlier in September.

‘Every day we see reports of systemic crimes within the regime and the ongoing arrests’, she added, referring to the recent detentions of former high-ranking officials.

Before his arrest, Khabeishvili dismissed such criticism.

‘If you don’t tell a fighter where you’re going, when you’re going, and what you’re doing, how are they supposed to follow you?’ he said in a 10 September interview, adding that opposition politicians ‘make their biggest mistake by not believing in the people’.

Khabeishvili’s party colleagues have echoed this line, including UNM member Ani Tsitlidze, who accused some opposition figures of elitism, saying they ‘love themselves more than the struggle’.

‘It’s wrong to focus on the idea that because we’ve failed to achieve change for 13 years, this day might also fail’, she told Palitra News.

According to Tsitlidze, if nothing comes of 4 October, she’ll keep fighting the following day. Still, she has argued that success is possible — after all, she says there are ‘many important factors’, including what she describes as the ‘weakness’ of Georgian Dream.

Only time will tell how this date marks the future of Georgian politics.