The Georgian Government is committed to fully exploiting the country’s hydropower potential. Collective mobilisation against mass construction of hydropower plants has began to emerge, but activists say they are met with exclusion and repression.

The Georgian Government is committed to fully exploiting the country’s hydropower potential. Collective mobilisation against mass construction of hydropower plants has began to emerge, but activists say they are met with exclusion and repression.

Energy Projects in Georgia is an emerging social group mobilising as a counter-movement to growth oriented investment projects that they believe will negatively affect people’s livelihoods, the environment, and cultural heritage in Georgia. The group — composed of activists from water-rich mountain villages from across the country — is the single precedent for sustained, cross regional cooperation and collective mobilisation on an environmental issue in Georgia.

‘Talk as much as you want’

In the early 2000s, when DSL internet first came to Georgia, one of the biggest telecom companies used for their advertisements the slogan: ‘talk as much as you want’. The phrase surfaced in Zura Nizharadze’s memory as he explained to OC Media the history of protests against construction of dams in Svaneti.

‘The situation where we were forcefully silenced has changed into a “talk as much as you want” approach’, says Nizharadze. A schoolteacher in the Svan village of Khaishi, Nizharadze is a long-time activist against hydropower plants in Svaneti.

‘We are happy that the state has opened up, that there is no more repression, but on the other hand, look what they did to us in Sakdrisi, they took it from under our noses’, adds Nizharadze.

He is referencing the months-long struggle to defend what has been called the ‘oldest gold mine in the world’, from being exploited for resource extraction. Sakdrisi was blown up by private mining company RMG Gold in December of 2014, only a day after the Ministry of Culture removed it’s status as a protected cultural monument. This happened despite widespread public opposition and questionable legal grounds.

[Read on OC Media: Government idle as mining companies wreck the environment in Georgia’s ‘sustainable development’]

Political exclusion in development projects — from Soviet times till now

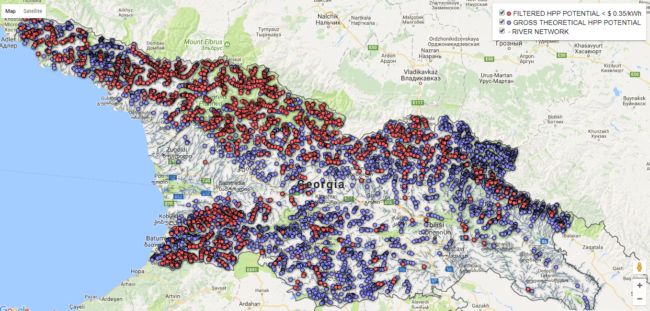

locations of HPPs in Georgia

Adilar Chartolani, 88, formerly a chief surgeon in Mestia and Eter Mchedliani, 87, formerly editor of a local newspaper, recall that the construction of the largest dam in Georgia — Enguri — between 1961–1978, had detrimental effects on the region, but that there weren’t the resources or opportunities to resist the project in those years. The first resistance movement against construction of dams in Georgia emerged in the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union began to open up, and also had less capacity to execute large-scale development projects.

Maia Kakhiani, a school teacher in Mestia, was a student activist during hunger strikes in 1989 against another damn — Khudoni. She says that it was the national liberation movement inspiring and leading demonstrations against dams in the late 1980s, but that now people often resort to religious and customary practices to sustain resistance movements instead. ‘There was no need to resort to traditional customs in the 1980s, we had the nationalists, but now that we are so alone it becomes a necessity to resort to traditions to halt the processes’ says Kakhiani, speaking of a group of men who recently swore on religious icons to fully commit to the struggle against hydropower projects.

Modern technological advancements in communications, and the spread of social media, has made it much easier for citizens to voice political opinions in Georgia. But for the residents of small regional towns and villages, unhindered communication only grants the freedoms to ‘talk as much as one wants’, with no opportunities to be heard or guarantees they will be listened to.

According to many residents of mountainous areas that OC Media spoke with, during the rule of Mikheil Saakashvili’s United National Movement, they were never even informed of government seizures of land for investment projects, but that political exclusion still persists today.

Consecutive governments under both the United National Movement and now Georgian Dream have followed a developmental agenda to build 100 hydropower plants in Georgia — according to activists, without public discussions or consent. While environmental activists and civil society groups have ensured that people are now better informed than ever — they still complain of being excluded from political participation — leaving only the most radical forms of protest viable for resistance.

According to the people OC Media spoke to, the only chance to express opposition to such projects appear once the construction crews and machinery start to arrive in their villages. Local residents often then block roads and rally around customary practices of defending the land.

[Read on OC Media: The downsides of hydroelectric power stations in Adjara]

When political exclusion is coupled with repression

In addition to complaints of total exclusion from the development agenda, activists and local residents tell stories from 2014 and 2015 which suggest the government strong-arms any opposition to development projects. Lile Chketiani, an art teacher from a village Chuberi in Svaneti recalls protests in the summer of 2015 in which people who recorded a clashes with police on their phones were ordered by police to delete their footage. Chketiani says that she was one of the few who disobeyed, later uploading the material online.

Members of Energy Projects in Georgia often talk of the government restricting access to public presentations and discussions, both in Svaneti and Kazbegi, with local people physically barred from entering. When the Nenskra Plant was announced, residents of Chuberi were prevented from accessing the site by security forces, complains Zaza Vibliani, another young activist from Svaneti.

‘This is not a campaign that we have, we are rather in a fight with the police and security forces every time we protest’, Zaza Tsiklauri told OC Media, recalling the detention of eight people during protests in May 2016 against the Nenskra hydropower plant, and his detention along with several others in Kazbegi for protesting against construction of power lines close to human settlements.

Tsiklauri, another active member of the group from Kazbegi, is trying to prevent the possible construction of 11 micro and large-scale hydropower projects in his region. All are part of the government’s development agenda.

The original Energy Projects in Khevi Facebook group (later renamed by Tsiklauri) was the basis for Energy Projects in Georgia. ‘Now we unite active citizens from Mtiuleti, Svaneti, Adjara, and Racha that are worried for their regions, and criticise projects inflicting harm on the whole population. We go to Svaneti when they need us and they come to Mtianeti to us’, says Tsiklauri, of those precedents when cross-regional mobilisation has occurred.

One of the more serious attacks by the government on protesters in Svaneti has been to introduce a restriction on the sale of timber, ‘the government tries to manufacture consent for dam building by cutting off major sources of Nakra residents’ livelihoods’, says Vibliani, a resident of Nakra. Locals also speak of fears of having state subsistence allowance terminated or being dismissed from jobs if taking actions to protest.

Local activists also speak of state officials purposefully misinforming the population that the protesters are the actions of a ‘controlled minority’. ‘They either call us dark powers or controlled or hostile groups. We are sometimes also told that there are different powers standing behind us. If only there was anyone — we would ask to be lead but not “controlled” ’, says Tsiklauri, cynical about the accusations.

Activists biggest complaint is that the government is planning and executing projects, which as far as they are concerned, are against public interests. The planners behind these projects are nothing but a ‘mafia group’, complains Tsiklauri, with ‘officials as their notary bureaus’.