In their preliminary findings on the 2 October local election in Georgia, the OSCE-led observation mission cited ‘widespread and consistent allegations of vote-buying’ as having marred the vote. Survey data from earlier in the summer sheds further light on the problem, suggesting that 16% of people know someone who has been offered a bribe for their vote.

In recent years, there have been increasing concerns over the conduct of elections in Georgia. Such concerns are well documented in international reports and academic projects that advocate for democracy.

The Freedom House 2021 report underlined democratic backsliding over recent years, and said the 2020 Parliamentary elections were ‘marred by vote-buying’.

According to the Varieties of Democracy project, which relies on expert surveys, Georgia’s scores on free and fair elections have been declining since 2017. This decline is largely driven by deteriorating scores in the vote-buying component.

A recent ISFED/CRRC survey offers a snapshot of people’s attitudes towards and experiences of vote-buying in Georgia.

How many people know someone that sold their vote?

In total, 12% of the public reported that they knew someone whom a political party had promised personal gain in exchange for their vote. Regression analysis suggests that Georgian Dream supporters were 17 percentage points less likely to do so than opposition supporters.

One in ten voters said they knew someone whom a political party or candidate had actually given money or a gift to in exchange for their vote over the past year. Regression analysis suggests people living in rural areas and opposition supporters were significantly more likely to report that they know such people than people living in urban areas and supporters of the ruling party.

Regarding vote-buying practices on election day specifically, 10% of the public said they knew someone whom a party representative or coordinator asked to vote for a specific party in exchange for money on the day of an election. According to a regression analysis, Georgian Dream supporters, people living in poorer households, and older people were less likely to say so than opposition supporters, people living in rich households, and younger people.

In total, 16% of the public said that they personally knew someone in one of the three categories noted above.

Regression analysis suggests people living in urban areas, supporters of the ruling party, and people living in poorer households were less likely to report acquaintance with someone who has experienced vote-buying than people living in villages, opposition supporters, or unaffiliated voters, and people living in richer households.

Are Georgians concerned?

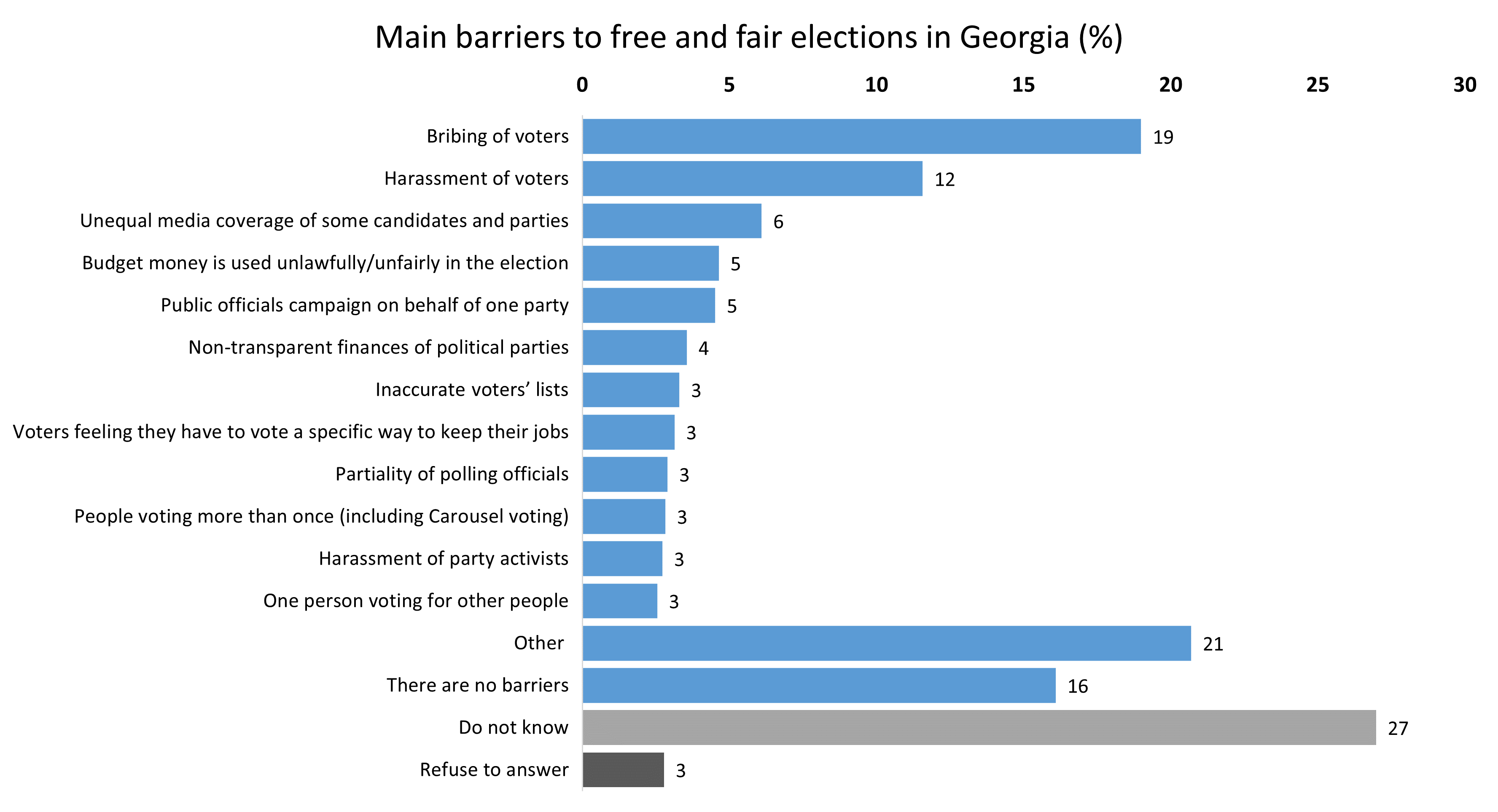

One in five people named vote-buying as the main barrier to free and fair elections in the country.

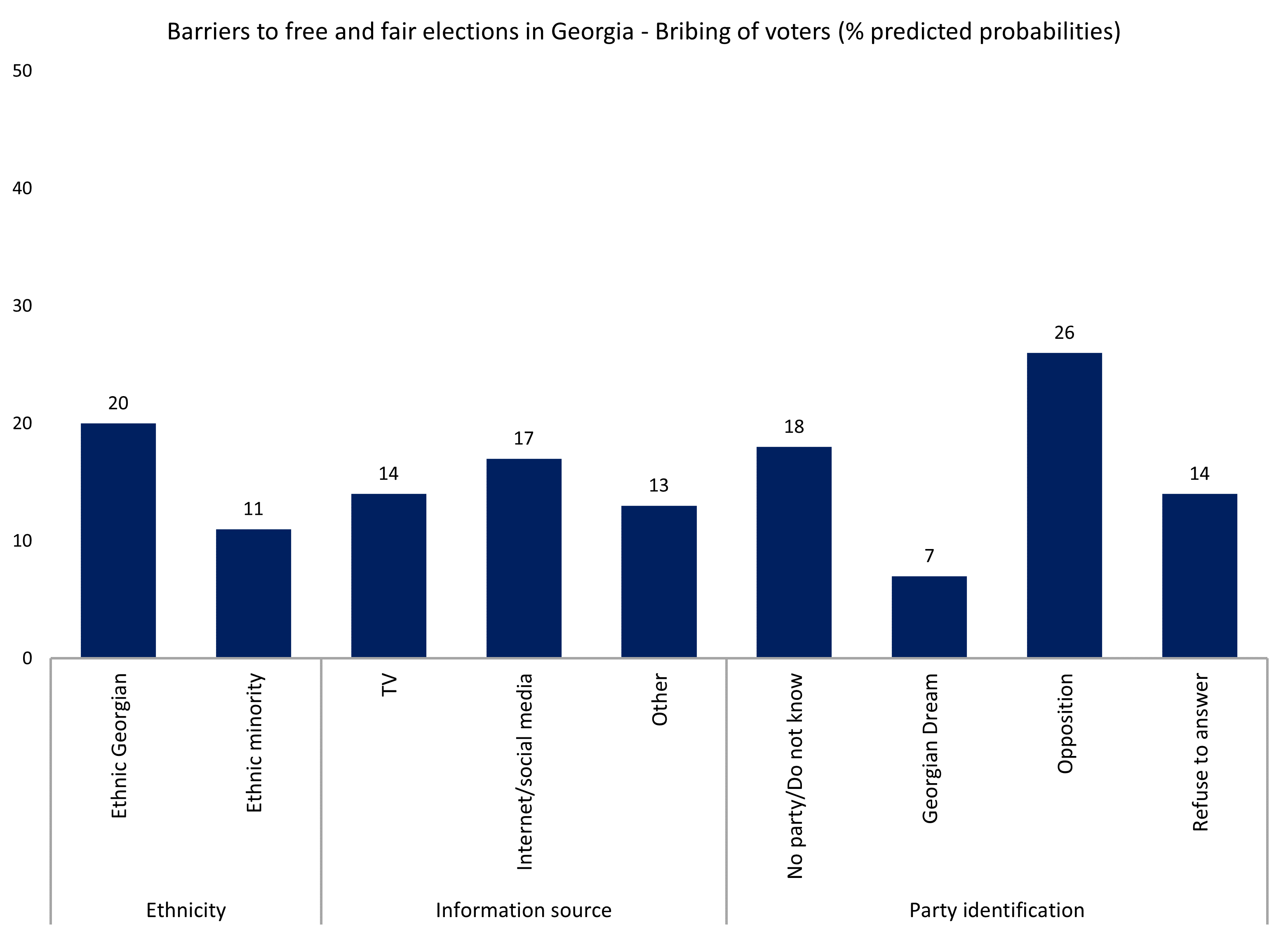

Supporters of the ruling Georgian Dream party were less likely than other groups to name vote-buying as an issue.

Half of the public (54%) named one or multiple obstacles to free and fair elections in Georgia, while 27% reported that they did not know what barriers there were and 16% said there were no obstacles to free and fair elections.

One in five (19%) said vote-buying was one of the most important barriers to proper electoral conduct, while 12% named harassment of voters. Smaller portions of the public named other obstacles.

Vote-buying was named by a number of different groups as one of the main barriers to free and fair elections more often than others.

All else equal, ethnic Georgians, opposition supporters, and people who mostly get information about elections via the internet or social media were more likely to think that vote-buying impairs Georgian elections than ethnic minorities, Georgian Dream supporters, and people who watch TV.

That 20% of people believe vote-buying is the main barrier to free and fair elections in Georgia and 16% personally know someone who has been subject to vote-buying portrays a gloomy picture for Georgia’s democratic prospects.

All this, coupled with recent international concerns regarding Georgia’s commitment to a democratic path should be troubling for Georgians.

Note: The above data analysis is based on logistic regression models which included the following variables: age group (18-34, 35-54, 55+), sex (male or female), education (completed secondary/lower or incomplete higher education/higher), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), wealth (an additive index of ownership of 10 different items, a proxy variable), employment situation (working or not), IDP status (forced to move due to conflicts since 1989 or not), ethnicity (ethnic Georgian or ethnic minority), primary source of information (TV, internet/social media, other sources), and party identification (Georgia Dream, opposition, no party/DK, refuse to answer).

The data used in this analysis is available here.

This article was written by Givi Silagadze, a researcher at CRRC Georgia.The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.