From 13 April, marches, meetings, and other acts of protest took place across Armenia as part of the ‘My Step’ initiative from the Civil Contract Party, and their leader Nikol Pashinyan. Protesters were struggling against the premiership of Armenia’s third President, Serzh Sargsyan. In the weeks of demonstrations, students made up the bulk of the protesters committing acts of civil disobedience, throughout Yerevan and beyond.

From 13 April, marches, meetings, and other acts of protest took place across Armenia as part of the ‘My Step’ initiative from the Civil Contract Party, and their leader Nikol Pashinyan. Protesters were struggling against the premiership of Armenia’s third President, Serzh Sargsyan. In the weeks of demonstrations, students made up the bulk of the protesters committing acts of civil disobedience, throughout Yerevan and beyond.

The beginning of the struggle

Before the start of the 13 April rally — the rally that kicked off the revolution — then opposition leader and now Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and his supporters underwent a march from the Armenia’s second city of Gyumri all the way to the capital. Over 14 days they overcame 200 kilometres, through major and remote communities, to reach Yerevan.

On the evening of 13 April, the anti-government rally launched at Yerevan’s Liberty Square. Nikol Pashinyan spoke of his intention to initiate peaceful civil disobedience, and protesters blocked France Square in central Yerevan and started a sit-in strike.

‘When the protest actions of the “My Step” movement started, I immediately joined because I want to live, study, and work in a free, independent Armenia; in a country the leaders of which are not gangs, but trustworthy, fair, clever people chosen by the nation, in Armenia, where the rights of students and others are not violated’, 18-year-old Ani Hakobjanyan, a student at Yerevan State University, tells OC Media. Ani says that during the struggle, the main difficulty was to fight against her own feelings.

In the initial days of protests, most of Ani’s classmates did not join her. She says that only 3–4 of her fellow students came out.

‘Some police officers were really inhumane to us, they hit us, once they even cursed at us; but some policemen tried to protect us from violent people. There were some provocateurs trying to distract us, calling for violence, disturbing us, and I didn’t know who to trust and who not to, which policeman to smile at and which to avoid. It was hard, and sometimes discouraged me. The biggest problem was with my mum. She didn’t want me to spend the night outside; she worried about me and even tried to take me home. But I didn’t go home for about three weeks: I couldn’t leave the struggle’, recalls Ani.

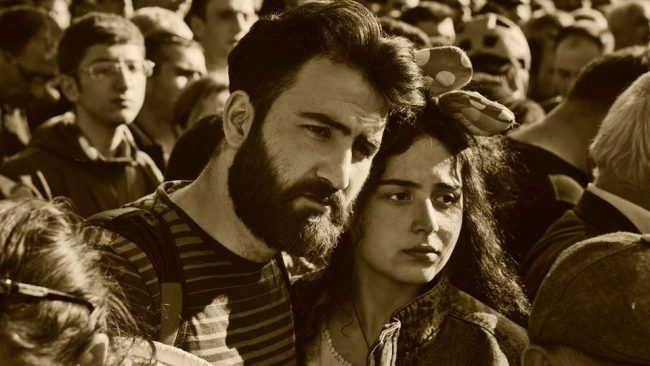

Ani was not alone during these days. Her boyfriend, 25-year-old student of Yerevan State Linguistic University, Mikayel Nazaryan, was with her.

‘This step was not the beginning of the struggle, it was a continuation of the process which would finally record a success’, says Mikayel.

[Read on OC Media: Heard but not seen: how women became the unrecognised architects of the Velvet Revolution]

Political passionate games of Armenia

The 16th of April was one of the hottest days of the struggle. Demonstrators tried to block the streets leading to Armenia’s parliament, the National Assembly, but they did not succeed. For making such an attempt, the police arrested dozens of demonstrators. Concentrating large numbers of forces on Baghramyan Avenue, leading to the NA, the police installed barbed wire. After a minor clash, with police using stun grenades, people both from the demonstrators’ side and the police were injured. Pashinyan was also injured.

On 17 April, during the NA extraordinary session, the third President of Armenia Serzh Sargsyan became the prime minister with 77 votes for and 17 against. On the evening of the same day an opposition rally took place at the Republic Square, during which Nikol Pashinyan announced the launch of a ‘velvet’ and non-violent revolution.

On April 18, the opposition launched a blockade of several government buildings. The students started massive strike.

Students — ‘the spark of the revolution’

‘When the rallies first began at Freedom Square, most people were over 40 years old… And to tell the truth, at that time I had an inner conviction that people’s hopes would be broken again in the end. But from Monday 16 April, everything changed after students began to stand up… I think students were the spark of the revolution’, says 23-year-old Hakob Gyozalyan, who studies at Yerevan State Medical University.

According to the students, there was not a single higher education institution in Armenia where protests would not take place over the coming weeks.

‘At the start of the struggle, only a few of our students came to the rallies, then after 16 April about 60 students from our course were striking’, says Ani.

The voice of thousands of demonstrators was heard on 23 April, when Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan submitted his resignation. He was replaced by First Deputy Prime Minister Karen Karapetyan, against who protests continued. Shortly thereafter, Karapetyan and his team also stepped aside, and on 8 May, Nikol Pashinyan was elected Prime Minister by the National Assembly.

‘The main factor in our success was the involvement of a large number of students, thanks to which we will still celebrate many victories[…] It’s impossible to stop people who have tasted victory’, says Mikayel.

‘This was really a great victory for the students, and we needed this victory. We were delighted and realised that we can win if we become one united fist. However, it would be wrong to attribute the victory only to students, because other people participated in the struggle as well. This was the victory of the Armenian people, and the students are at their core’, says Ani.

‘For me, the victory was not the change of personalities, but the change in people’s consciousness, a change of love and trust towards the country, a change of hope for the future. This is the victory for me’, says Hakob.

The lecturers helped the students

‘During these days [for almost a month] I didn’t go to classes, and I learned from my fellow students that our lecturers not only were not suppressing them, but praised me, and then their own participation as well. And after everything came to an end, when I went back to university, everyone was very warm and asked what interesting things happened during the demonstrations — where I had slept or whether I was hurt. My lecturers had pride and happiness in their eyes’, recalls Ani.

During those days, Arayik Harutyunyan, a lecturer at Yerevan State University, and member of the board of the Civil Contract Party, stood beside the students. Harutyunyan was appointed Minister of Education and Science after Nikol Pashinyan’s election as prime minister.

In Gyumri, where thousands protested as well, rallies were headed by a lecturer from the Gyumri branch of the Armenian State University of Economics, Acting Head of the Chair of General Economics, 36-years-old Karen Petrosyan.

‘The role of the students was of course great. The people had a special, divine inspiration: they were convinced that they would win. Joy was spread to everyone.’ says Petrosyan.

‘People were trying to undermine the will of the students, but they were happy, they would get arrested, but they were happy […] The legal awareness of our youth is very high. They had participated in various protests before, had been repeatedly detained, and they already knew the laws. Thus, when they were taken to the police station, they were able to stand up for their rights.’

According to the Petrosyan, these rallies have also helped to solve another problem in Armenia: the relationship between lecturers and students.

‘Until these events, many lecturers were somehow convinced that their students were subjects who they could treat however they wanted. As in the whole state system of the Republic of Armenia, so too in higher education institutions, human relations were built on the basis of fear. This was an opportunity to express these accumulated emotions. Our students were not afraid of anything, and no threat could stop them’, says Petrosyan.

According to him, it is a great mistake to draw a line between a student and a lecturer. He recalls that in his student years, he demanded lecturers remember that as human beings, everyone has equal rights; the difference is in responsibilities and duties.

‘There are no different rights and obligations during the protest actions; we are all equal before the law. In those days, only the issue of seniority came forward. They accepted me as a senior friend and leader and I had some responsibility for their safety’, recalls Petrosyan.

At first, only a few of Petrosyan’s colleagues stood beside him, but as the number of student demonstrators swelled, so too did the number of lecturers taking to the streets.

‘People do not always want to be the first ones in such cases’, Petrosyan remarks.

After his leadership of the local movement, students in in Gyumri and others as well have called for Karen Petrosyan to be recognised for his role, and there is a growing movement in Shirak Province, of which Gyumri is the centre, to appoint him governor of the region.

This article was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of FES.