Unionising is seen as unappealing and even dangerous by many Georgians, but some new public and private unions are gaining support, taking on their employers — and winning.

For decades, Georgia’s labour unions have been a mostly unsuccessful endeavour. While big enterprises are plagued by company-dominated unions or take revenge against unionised workers, 29% of the workforce is informally employed and 21% unemployed.

With two of Georgia’s largest employment sectors — hospitality and construction — characterised by frequent workforce rotation, and a broader public mistrust of the justice system, unionising has become unpopular and even potentially dangerous, with young people having little to no recollection of how it might help them.

[Read more on OC Media: Datablog | Youth in Georgia have little trust in unions]

Georgians seem to have mostly followed their employers’ implicit or explicit suggestion that they ‘take it or leave it’, unionising only when there’s little other alternative and conditions are so unbearable that a strike seems the only viable course of action. Even then, many unions struggle to maintain themselves and remain active in the longer term.

However, since 2019 new, younger unions have achieved modest successes that are worthy of examination, and could pave the way for a shift in attitudes.

‘No place for indifference and nihilism’

The Social Workers’ Union was established in April 2019 following an eight-day strike in which 295 employees — nearly the entirety of social workers in the public sector — participated.

During the strike, social workers in Georgia demanded an increase in salaries, fewer cases per individual, and for their transport costs to be covered, and achieved a remarkable result, receiving an immediate 30% rise in their salaries.

However, any success was swiftly eclipsed by the post-strike ‘revenge’ staff cuts that targeted prominent strike activists.

It was then that Ketevan Khutsishvili, along with other fired workers, realised that creating a union would be an appropriate response to defend their rights. To date, it is one of the most legally successful unions in the country — out of 25 cases taken to court, they have won 20, and are confident about winning the remaining five. Fired employees have had their positions restored and been paid the missed hours.

The Social Workers’ Union now has 170 members, including public sector workers and NGO staff as well as current social work students. The board of nine members makes most of the decisions, and the chair is elected every year. A revision commission separate from the board handles finances and paperwork.

The monthly membership fee is a minuscule ₾3 ($1.10), barely enough to keep the union running, but seemingly impossible to increase.

‘We acknowledge this is a problem, as we have to seek external funding and be project-bound,’ says Ketevan Khutsishvili, ‘but we also cannot ask for more, people simply won’t be able to pay’.

Apart from defending fired workers in court and protecting their rights in the workplace, the union works on improving working conditions by conducting internal research. This year, they published a critical evaluation of the Labour Inspection Service’s effort to address their needs. The Labour Inspection Service (LIS) is the state body tasked with ensuring that employers comply with labour norms.

‘The problem is that the Labour Inspection Service doesn’t understand the specifics of our job and operates within the labour code — for example, when monitoring overtime. But apart from the labour code, we also have the 2018 law on social work that says that agents shouldn’t have more than 50 cases on their hands. Meanwhile, we often had 100, 150 cases at once, but as long as we worked within our working hours, the Labour Inspection Service didn’t recognise it as overtime work’.

Although the LIS hasn’t taken any action since the union published their assessment, Ketevan and her peers hope the department will at some point make changes based on their findings. ‘We are determined to work together with them to establish a useful mechanism for protecting our rights’.

Such unity and persistence are uncommon in the world of Georgian labour unions, and Ketevan attributes their success to the specifics of the job:

‘We always stress that we fight for the rights of our beneficiaries. If you’ve been fired, or you don’t have transport or a private room to talk to your beneficiary, you will not be able to help them. There’s no place for nihilism or indifference in this job.’

The social workers’ union is not part of the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC).

‘We always strived to be as independent as we could. We also monitor our representation in the media and deny any politician who tries to claim alliance with us, but we are open to both the government and opposition MPs to lobby our interests in the parliament, as long as we’re not affiliated with them’.

‘Why shouldn’t “First job” be the best job?’

Throughout the Tbilisi Metro, billboards emblazoned with the English-language slogan ‘First job’ show young, happy people, but provide no indication of what that ‘first job’ might be.

They are advertising Evolution Gaming, a major employer of students in Georgia — approximately three-quarters of their 7,000 staff are studying, according to employees. The prospective workplace is essentially an online casino where virtual players gamble at real tables, live, 24 hours a day; the cameras never stop.

The most common jobs on offer are game presenter and shuffler, both of which require physical resilience, precision, and almost constant communication, as they spend a lot of time standing, meticulously placing cards, and talking to players.

The performance of presenters and shufflers is evaluated by a separate team that closely watches the employees and subtracts from their bonus every time they make a mistake. One look sideways, a card placed slightly off, or going silent for more than six seconds can cost you a cut of your salary.

The base salary for game presenters is ₾7.10 ($2.60) an hour, but 22% of this goes to pension and tax, leaving workers with around ₾5.6 per hour ($2.06). After 18 months, the take-home salary grows to ₾6.40 ($2.35).

However, a complicated performance-based bonus system can add 10%, 20% and 30% bonuses on top of the base salary. This system is not part of employees’ contracts, and is flexible in a way that seems to always end up favouring the employer.

It was in part this system of bonuses that inspired the Evo Union — an organisation founded by and advocating for game presenters and shufflers.

‘There was a strike four years ago that wasn’t effective, and a lot of people got fired’, says one of the Evo Union’s leaders, Tamar Ansiani. ‘We decided to take a different approach.’

This August, after another change to the bonus system, Tamar and several of her colleagues started posting their concerns in the Evolution Gaming Facebook group, which includes all Evolution Gaming employees.

The group produced a smaller Messenger chat of like-minded workers, who, along with the change to the bonus system, brought up all their accumulated grievances at the company — hot, stuffy air that made some workers faint, insect bites and dirty gaming tables, unsanitary conditions in the locker rooms, and breaks whose length and frequency seemingly depended on how a particular floor supervisor felt on that day.

Nika Katapariashvili, another Evo Union member, recalls the backlash he faced after he tried to speak up publicly.

‘I wrote on Facebook: “this company deserves a strike for how unfair it is”. One hour later, my supervisor called me in and spent all my break telling me how I was an enemy of the company and that if I didn’t delete the post, they’d fire me.’

Nika deleted the post, but immediately posted about his experience with his supervisor. After posting, he was assigned 14 tables, seven hours in a row, without a break.

Not long after, Tamar and Nika noticed that a change had taken place in the group — all posts now had to be approved by an admin.

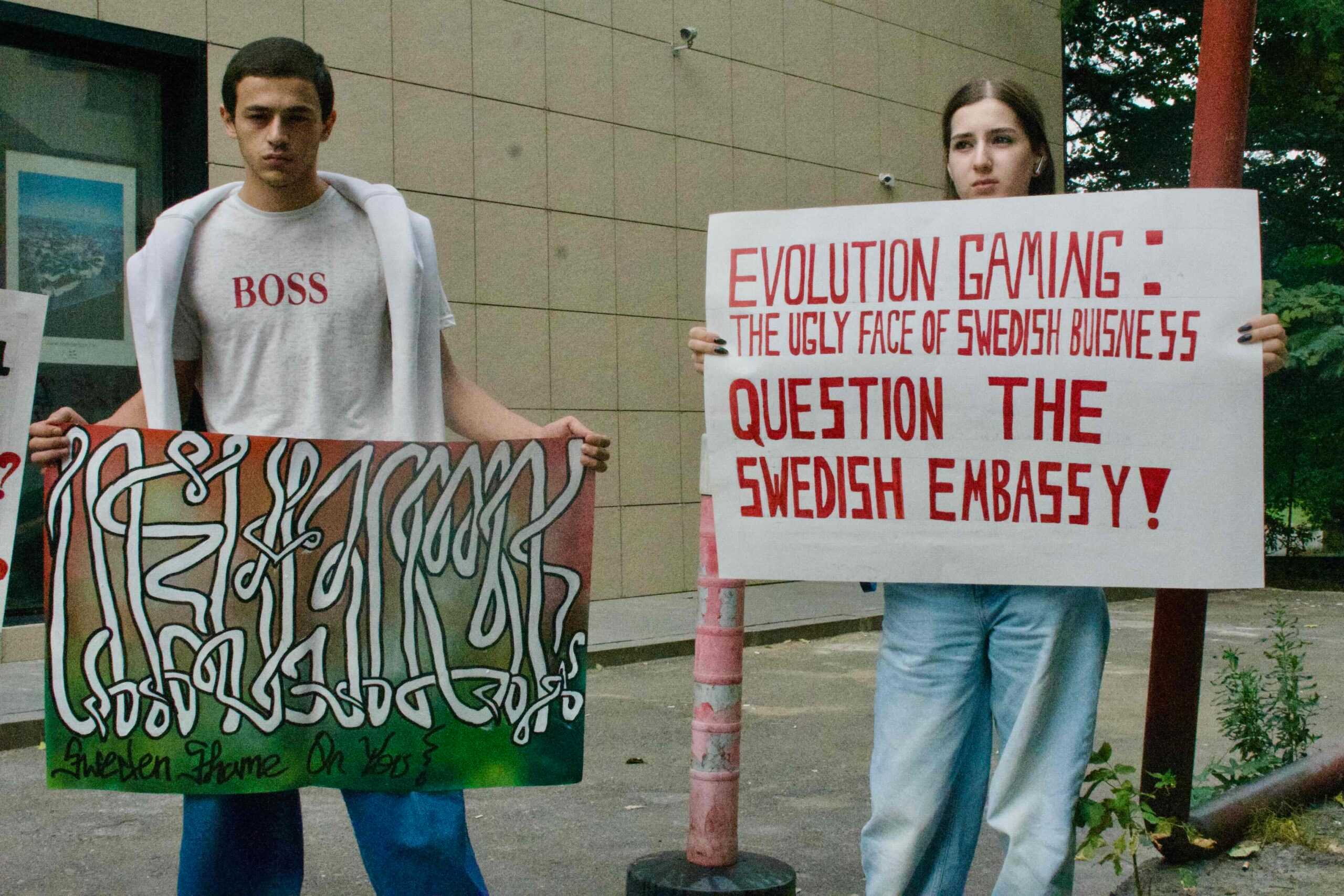

They gathered all the evidence, and together with their colleagues, filed a complaint with the Public Defender and Labour Inspection Service. In August, with the help of the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC), they presented the management of Evolution Gaming with a list of demands: include the bonus system in the contract, allow sick leave notes from all clinics (rather than just those covered by Evolution Gaming’s insurance provider), lift the six-month ban on working in a similar company after leaving Evolution, and have a doctor on site. Crucially, they demanded that workers be given a yearly raise in line with inflation.

The whole list consisted of 37 points. But since the demands were submitted, the company has begun work on only two of them — the issue of sick leave notes and providing game presenters with a foot rest. The rest of the demands were noted, but the managers are taking their time to respond.

Merely achieving a meeting with the company’s management was a struggle — employers agreed to sit down with the union only in mid-November, nearly two months after the request.

Tamar thinks that the Public Defender’s Office played a role in making the meeting happen, as it took place shortly after the Public Defender questioned the management as to why they were not engaging with the union.

Evo Union is less satisfied with the Labour Inspection Service, as it failed to highlight some important issues in its report and as it turned out, gave some remarks verbally.

‘In the meeting, the managers mentioned that the inspection notified them about problems with the common toilets, for example, but these issues were not mentioned in the report’.

Evo Union has appealed to the Labour Inspection Service for a re-evaluation. Young people are determined to achieve the best conditions for themselves and their colleagues.

‘They call themselves “First Job”, but why not be “best job”?’ asks Shota Guruli, another member of Evo Union.

‘I have two jobs apart from this one, so I have somewhere else to go. But I choose to stay because I really believe we can change things through negotiations. The company will only benefit from a decent [working] environment.’

‘I never used to believe in unions, but now I’ve seen that together, changes are possible, and I am not alone. I want Georgia to have good labour conditions and good companies.’