‘Help must reach the people of Iran’ — Iranians demonstrate in Tbilisi and Yerevan

Alongside the protests in their homeland, Iranians in Georgia and Armenia are holding solidarity rallies, filled with anger, grief, and fervent hope.

Starting from the first week of January, Iranians in the Armenian and Georgian capitals have begun to gather near their respective embassies every evening. Like many in the diaspora, they are seeking to express solidarity with the nationwide, heavily suppressed anti-government protests in their homeland.

Given the modest presence of Iranian nationals in both countries, the protests are not large in scale, yet they are loud, expressing the anger and despair of those living away from their homeland in the face of the mass repression their compatriots endure on the streets back home.

‘They are criminals, they are killing us with machine guns, it’s not a good regime for us’, Hossein, an Iranian demonstrator in Yerevan, tells OC Media.

Protests that erupted in late December 2025 over economic grievances quickly spread nationwide, taking on a sharply anti-government character.

Although the first casualties were reported early on, repression intensified dramatically after 8 January, as protests expanded and authorities cut off the internet and other communications, effectively isolating the nation.

Reported death tolls are staggering, with estimates ranging in the thousands, depending on the source. Government officials have admitted themselves that as many as 3,000 could have been killed already, which would make the crackdown one of the deadliest incidents of violence committed by a state against its own people in decades.

‘They cut off the internet, phone, SMS, and any communication [even between] Iranians inside Iran, because they want to hide their crimes. They are doing mass killings, genocide inside Iran!’, Mariam Sharifi, a Tbilisi-based activist from Tehran, tells OC Media.

Lack of communication and shortage of news on the situation on the ground and from their loved ones keep many stressed and unable to find peace outside of Iran either.

‘All of my family members are there and I have no clue what they have been through and what they are doing right now — are they alive or not’, Artin, an 18-year-old, Tbilisi-based Iranian, tells OC Media.

‘Three years ago they arrested my cousin and I’m 100% sure he’s protesting again [...]. They threatened him, that if they caught him for the second time, they would execute him. There is a high chance that he gets arrested again and we have no clue about that’, he adds.

After days of complete blackouts, some were able to briefly re-establish contact with their families. It was this way that Mohammad Amin, who lives in Yerevan, learned on Tuesday from his mother that a friend of his in Iran’s Gilan province had been killed.

‘Many people are being killed in the streets, and their voices are not reaching outside Iran’, he says while protesting outside the Iranian Embassy in Armenia. He considers the everyday rallies an opportunity to ‘send this voice out from here, to make sure it reaches the ears of the entire world’.

‘Help must reach the people of Iran. We are asking you, please, help the people of Iran’, Amin says.

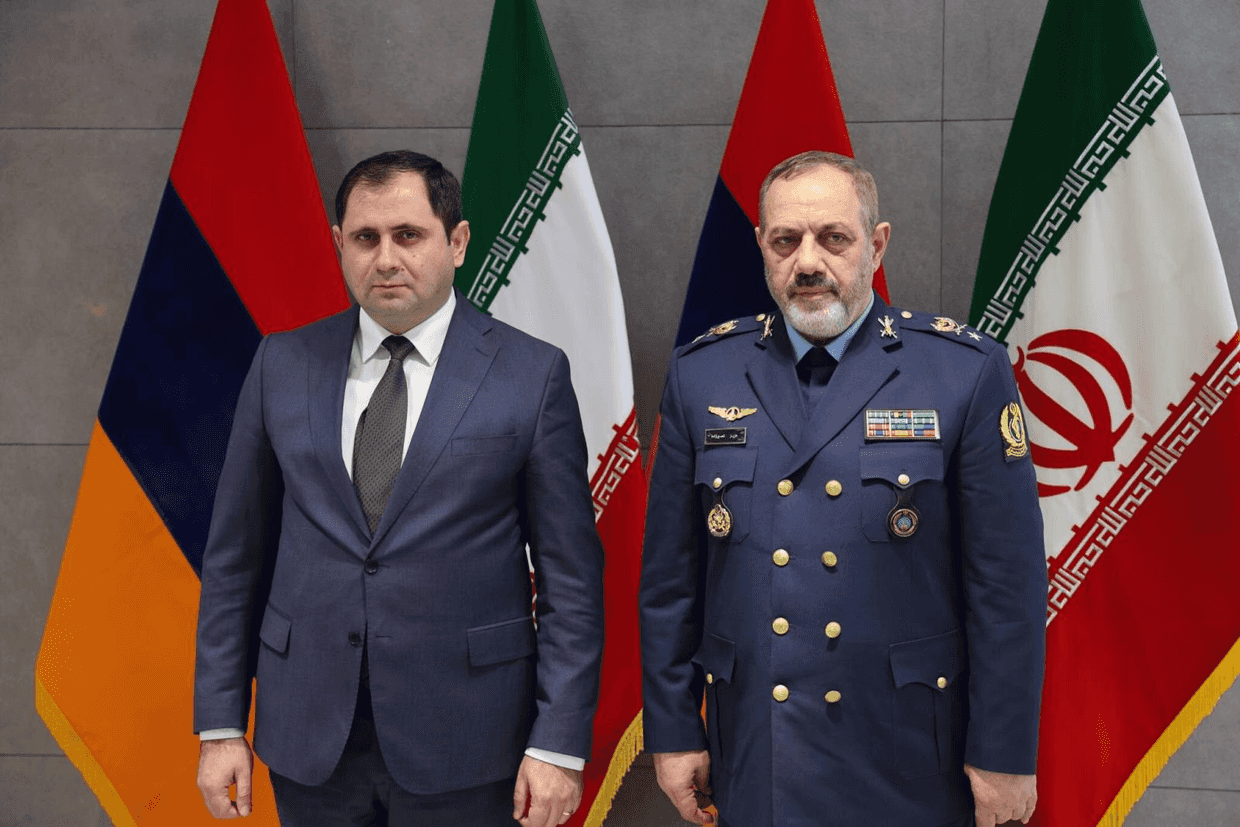

The demonstrations in Yerevan are continuing despite criticism by the Iranian authorities who are unhappy that Armenia, as a democratic country, is allowing the protests to take place. Tehran has further voiced its concern that ‘Armenia is becoming a hub for the actions of forces hostile to Iran’.

‘We are all fighting against dictatorship’

‘We will fight, we will die, we’ll take Iran back!’, a man shouted outside the Iranian embassy in Tbilisi on Wednesday, a chant soon taken up by other demonstrators.

It was one of many Persian-language slogans frequently heard at anti-regime rallies, often accompanied by patriotic and revolutionary songs.

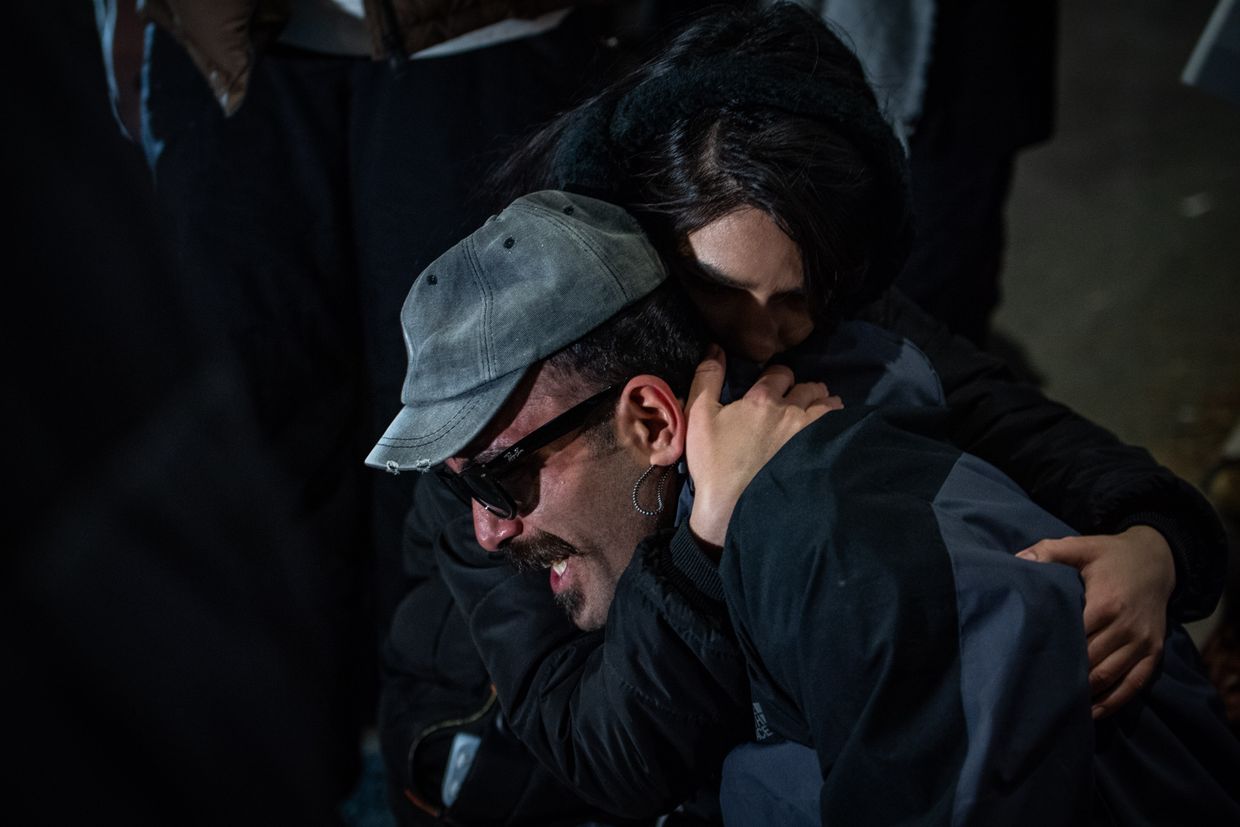

Scenes at the Tbilisi rally that day were especially emotional. At least three people required medical assistance — one reportedly after learning by phone of a family member’s killing, and two others due to acute stress.

Other demonstrators, including Georgians who had joined the rally in solidarity on Wednesday, were visibly moved to tears. In addition to Persian and English, slogans could also be heard in Georgian, including expressions of gratitude such as ‘Thank you, Georgia’ and ‘Long live Georgia’.

‘We are all fighting against dictatorship — each in our own way, and each paying different sacrifices in this struggle’, Georgian activist Nino Kalandia says. She attended Wednesday’s rally and is also an active participant in the daily demonstrations against the Georgian government.

‘The more entrenched a dictatorship is, the more it permits itself [to act with impunity], and we see this happening in Iran’, she adds.

At Wednesday’s rally, police detained Georgian activist Nutsa Makharadze on charges of disobeying the police and verbally insulting officers.

In both Tbilisi and Yerevan, the rallies have stood out for their age diversity, with Iranians of different generations attending — some alone, others with family members.

‘I’m against the Islamic Republic because they don’t allow our people to live’, a 13-year-old Iranian named Setare tells OC Media after getting permission from her mother to give an interview.

‘Instead of going forward like any other country has been, we’re going backward’, she adds.

Some of the older participants had experienced state repression themselves before leaving Iran.

‘Six years ago he joined the protests, and four years ago he was arrested,’ a young man tells OC Media while translating the account of another protester, Amin, from Persian.

‘He said his friends were executed by the government. They [injured] his hand, you can see it here’, he says pointing to Amin’s injured palm.

‘Revolution’ and its future

Despite the devastating news about mass killings and the government’s claims that they managed to shut down the protests, Iranians have not lost hope. They continue to call the ongoing movement a revolution and, in some cases, express a desire for external support, including from the US.

‘Have you seen the videos of Iran? The crowd is too much to explain anything other than revolution. That is happening, we know it will be bloody, but we hope that is happening now’, protester Sarah Setude tells OC Media in Yerevan.

The protesters use harsh language in their criticism of the Iranian government, describing it as ‘criminal,’ ‘terrorist,’ and a ‘dictatorial regime’.

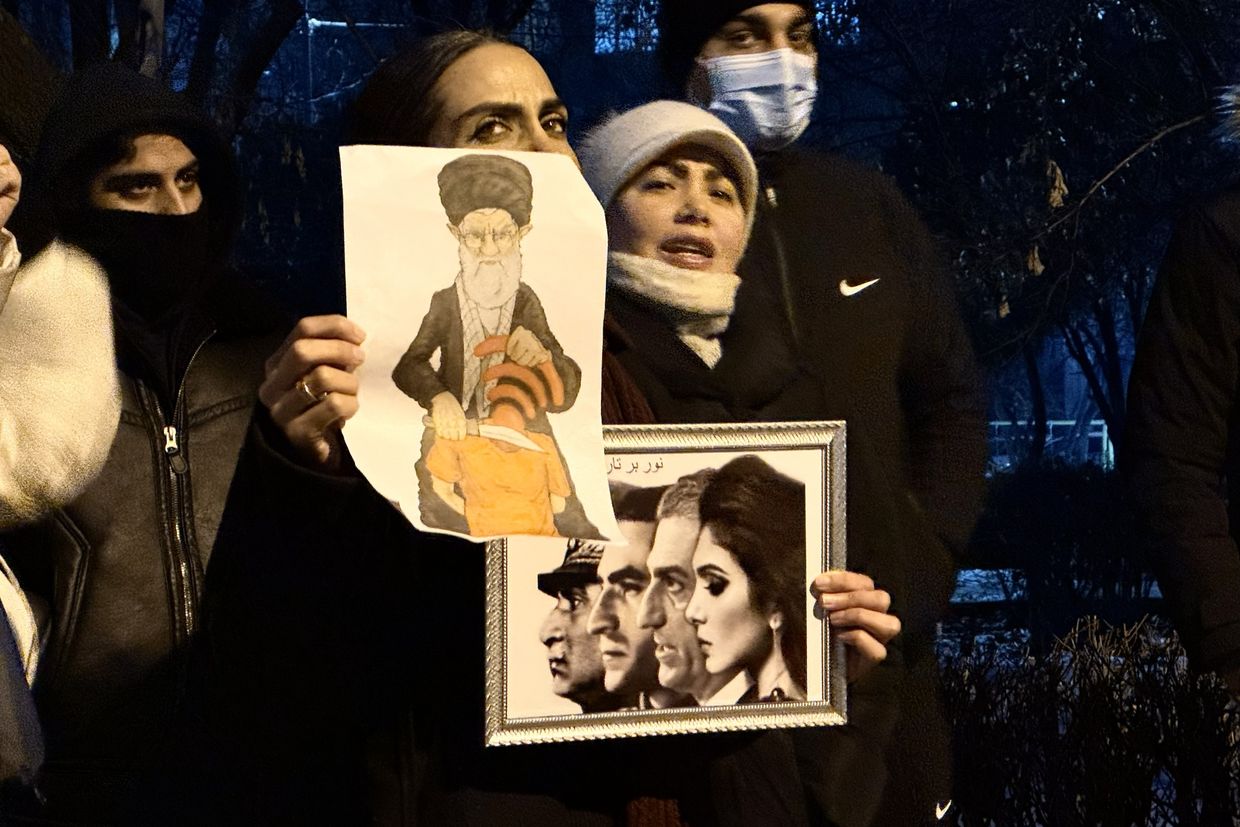

Their deep hatred toward the Iranian leadership is many times reflected in the slogans — from the emblematic chant ‘Death to Khamenei,’ referring to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, to ‘this homeland will not be a homeland until the mullahs are buried,’ a reference to the clerical establishment.

‘Our youth is ruined: we don’t have any economy, any future under our government’, Soroush Rad, 22, tells OC Media in Tbilisi, emphasising that ‘this atrocity has to come to an end’ while describing the protest crackdown.

Discussing the future of Iran, protesters often referenced Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of Iran’s last shah, Mohammad Reza. Overthrown in the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the shah’s rule is emphasised by supporters as an era of modernisation and economic development, while critics condemn it for authoritarianism, human rights abuses, and widening social inequality.

The exiled prince has emerged as an active voice in the current protests.

Both in Tbilisi and Yerevan, monarchist sentiment is widely visible, including through chants of ‘Long live the Shah,’ and pictures of the royal family. Support toward Pahlavi himself is obvious too, with many viewing him as a unifying figure amid Iran’s fragmented opposition and a potential leader of a future secular state.

‘Actually in the Pahlavi House, they've been really really really good people, good kings and they cared about Iran and Iranians a lot’, Setude says.

Rad, a staunch monarchist, agrees, saying ‘we want democracy, we want our king Reza Pahlavi back because he’s the only one who truly promises us democracy’.

‘Not by an individual, but through a constitutional process under an interim government,’ he adds, echoing what others have emphasised as well — namely, Pahlavi’s stated plan, upon returning to Iran, to call for a referendum to determine the country’s future system of governance, with a transitional council whose members would be appointed by him.

When asked about the risk of human rights in the reproduction of the monarchy system, Pardis Mokhtari in Yerevan said, ‘the king does not [re]present the monarchy, we call him the king of Iran because that’s his legacy, that's how his family came to Iran and he’s a leader’.

‘It does not mean that he’s going to come and make a monarchy or build another dictatorship’, Mokhtari added.

However, not everyone is so certain.

‘We should not simplify the demonstration to just one word and one person’, Sharifi says, referring to the particular focus on Pahlavi. She adds that at one of the rallies, ‘a very few people’ supporting Pahlavi even tried to stop her from chanting different slogans.

‘The majority of people agree on freedom and democracy. We don’t want just one person to come and take all power and kill other people and make other people silent. It is exactly what Islamic Republic did at the beginning of the revolution[...] We don’t want this story to happen again’, she says.

Despite the harsh circumstances in their homeland and emotional pressure, Iranians in both cities continue their protests, believing that removing the regime they are fighting against would bring benefits not only to their country but beyond.

‘It's not only about Iran, they spread evil all around the Middle East. If anybody wants to support peace and if anybody wishes for a peaceful world, they should stand with the people of Iran’, Mehrdad Rouien, a protester in Yerevan, says.