The number of new HIV infections in Daghestan in the first half of 2017 was up from last year. Doctors in the republic worry about the lack of public awareness — and a lack of resources.

The number of new HIV infections in Daghestan in the first half of 2017 was up from last year. Doctors in the republic worry about the lack of public awareness — and a lack of resources.

HIV is not a death sentence

Marat, 39, is HIV positive. He learned this 13 years ago. Marat has accepted his diagnosis and decided not to isolate himself from society, instead engaging in social activism.

‘I used to think HIV could only happen to people who use drugs or men with a non-traditional sexual orientation. But when it happened to me, not being either, I faced it and understood that it can affect anyone, everyone is under threat’, Marat told OC Media.

Marat met with a number of other young people in similar circumstances, and they established the regional organisation Svoi. Svoi provides support to members, and others faced with the same problems and challenges.

‘I never thought of becoming an activist. I became part of a new community. I didn’t want to speak about this topic but I was often invited to seminars about HIV/AIDS prevention. I would share my experiences — speaking about how I cope with this diagnosis’, Marat adds.

He says that there are two important stages once someone is infected: when they learn about their diagnosis and when they have to start taking medication.

‘You have to make the decision to take the medication, and then you’ll be taking them for your entire life according to a schedule. You cannot stop taking them or be late. This was a bigger blow for me than accepting my diagnosis’.

Marat’s life changed entirely after receiving his diagnosis; his wife left him, fearing that he could infect their child. He began to engage in activism. He never thought of having a new family, but soon met his future wife.

She knew that there was no cure for HIV, but that with proper care — and taking medication on time — it’s possible to create a family without becoming infected, and even to give birth to healthy children.

‘We are a discreet couple. When one of us is sick, the other is healthy. I knew that there are many couples like this in the world, but I never thought about having a new family. Infected people very often do not start families; they think HIV will stop them. However this is a stereotype and our family is a proof that it is possible to have a family’, Marat remarks.

When he was diagnosed in 2004, very few people believed that he would still be alive in 2–3 years. He proved that if you follow certain rules, HIV is not a death sentence, and it’s possible to live with it. He has two children with his new wife, and helps others to cope with the disease.

New infections on the rise

According to Daghestan’s Ministry of Health, 117 people were diagnosed with HIV in the first half of 2017, 16 more than same period last year.

According to Daghestan’s Consumer Protection and Welfare Service (Rospotrebnadzor), in recent years, the average age of infection has changed from 18–29, to 30–49. A majority (66%) were infected as result of unprotected sex.

‘The problem is that Daghestanis rarely take blood tests. They often only take them when they are a requirement’, Laura Umakhanova, a specialist at Daghestan’s AIDS Prevention and Control Centre told OC Media.

Blood tests are available in every major medical institution in the republic, both state and private, but not everyone knows about this. The centre runs an anonymous clinic, ensuring anonymity of patients in Daghestan.

Specialists from the centre describe frequent cases of infection being diagnosed in new couples, as some young people do not inform their partners about being HIV positive, with many considering it a shame to discuss it. They choose to hide it. As a result, very often women find out once they are already pregnant.

Knowingly infecting someone with HIV is a criminal offence in Russia, carrying a sentence of up to eight years in prison.

The Health Ministry and Rospotrebnadzor have repeatedly proposed mandatory HIV testing before marriage, but MPs have not supported the initiative.

‘Our MPs say that it is difficult to bring this idea under any legislative basis, and this is a violation of human rights. However Ramzan Kadyrov banned marriage in Chechnya without proof of HIV status’, Umakhanova says.

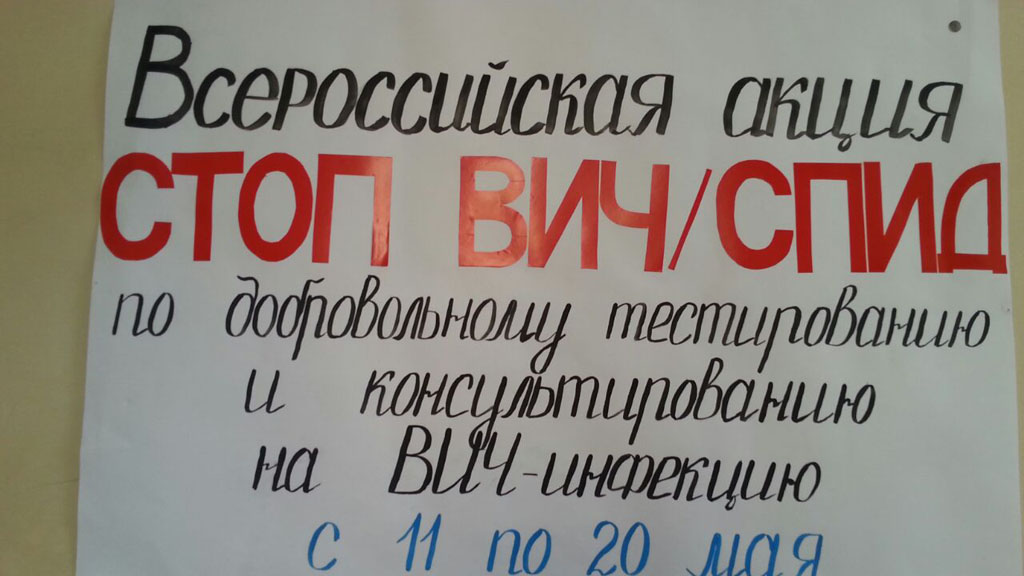

Umakhova says that there is lack of media coverage about this problem. Their centre tries to spread information about HIV/AIDS by printing leaflets, she says, but this is not really effective, while advertising on social media is expensive.

By the will of Allah

Employees of the centre say that not everyone accepts medical assistance after learning they are infected. According to Umakhanova, some completely reject treatment, saying it is the ‘will of Allah’.

Mukhammad Abdurakhmanov, a doctor from the Centre of Islamic Medicine, says that this attitude is wrong. He says that treatment in Islam is a fard (a religious duty).

‘The Prophet Muhammad himself was treated and called for the healing of other people. He said that Allah sends treatment along with illnesses. In Islam there are many hadiths about medical treatment. “Heal, oh, for the sake of Allah” is one of them. This is a fard’, Abdurakhmanov tells OC Media.

According to him, Muslims who voluntarily reject treatment are sinning.

‘If a drowning person is thrown a lifebuoy and refuses it, trusting instead in the will of Allah, it is a sin’, he explains.

Leaving Daghestan for treatment

Sabiyat Gadzhiyeva, an activist and director of Svoy, says that there are no proper, well-equipped centres for patients with HIV/Aids in Daghestan.

‘There are about 3,000 patients in Daghestan, but we do not have a hospital where you could send patients if needed. There is a department of hepatology in an infectious diseases hospital, but, for example in Chechnya, they’ve built a centre for HIV-positive people’, Sabiyat tells OC Media.

It remains only a dream in Daghestan to have a centre dedicated to offering services to HIV positive patients. This is why many with HIV/AIDS choose to leave the republic, to receive help in centres in other regions of Russia.

Svoy says that the real number of infected people is likely much higher than the official number, but they cannot tell the real numbers.